News

Cambridge Residents Slam Council Proposal to Delay Bike Lane Construction

News

‘Gender-Affirming Slay Fest’: Harvard College QSA Hosts Annual Queer Prom

News

‘Not Being Nerds’: Harvard Students Dance to Tinashe at Yardfest

News

Wrongful Death Trial Against CAMHS Employee Over 2015 Student Suicide To Begin Tuesday

News

Cornel West, Harvard Affiliates Call for University to Divest from ‘Israeli Apartheid’ at Rally

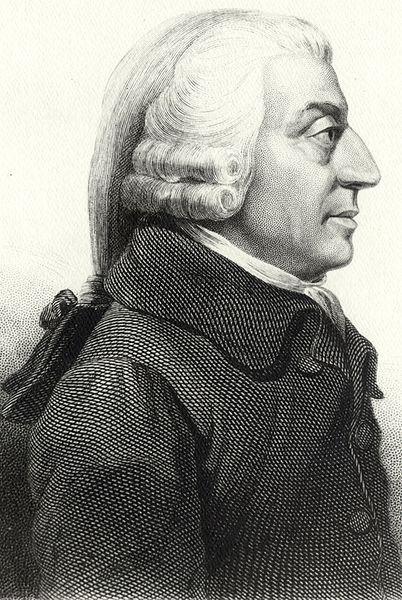

Empathy, Obama, and Adam Smith

Defending his nomination of former Harvard Law School Dean Elena Kagan to the Supreme Court, President Obama has studiously avoided the “e-word” that got him into so much trouble in the past: empathy. As a candidate, and then again when he nominated Sonia M. Sotomayor, Obama listed empathy among the most important virtues a justice could possess. His opponents insisted that the term could only be code for an “activist” judge, which in turn is code for a left-wing judge. But to understand Obama’s insistence on empathy, we need to consider the classic statement on the subject by an 18th-century author who is usually understood to stand on the right of the political spectrum: Adam Smith.

In October 2008, then-Senator Obama surprised many when he included two works by Adam Smith on a list of the books that most deeply influenced him. The question of whether “The Wealth of Nations” has been an inspiration for Obama’s response to our current economic troubles will have to be saved for another occasion. Smith’s other book, “The Theory of Moral Sentiments,” has had a more obvious effect on the president’s worldview.

Smith is an important source for Obama’s conviction that just and impartial judgment must be grounded in a sense of empathy for our fellow human beings. Although the president’s critics have insisted that justice must be blind and that empathy can only bias judicial opinions, Smith knew that justice would be an impossible ideal were human beings unable to share each other’s thoughts and feelings.

The word “empathy” was coined in the 20th century to describe our ability to feel our way into another’s point of view. Smith called this ability “sympathy.” He saw every instance of sympathy as involving an implicit form of moral judgment. When empathetically engaging with the situation of others, we are led to imagine how we ourselves would react in their situation and don’t sympathize with reactions that are inappropriate. This is why sympathy can serve as the basis for our sense of right and wrong, what Smith called our “moral sentiments.”

Sentiments of justice involve what Smith called “divided sympathy,” in which multiple individuals with conflicting interests are the objects of our empathy. When two or more parties are in conflict, we must empathetically evaluate each of them. Only after having done so can we determine to what extent each has behaved properly toward the other. And only after that can we determine the principles of justice governing the case at hand.

Consider the famous scene in “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” in which the slave trader Mr. Haley hunts down the heroine Eliza to regain the property that she stole from him. Although readers might conceivably sympathize with Haley as a victim of theft, we in fact only feel sympathy for Eliza. After all, the property she stole is her own five-year-old son. It is Haley, not Eliza, who is being unjust.

Smith goes on to argue that rules of justice can be generalized from our individual moral sentiments. We conclude that slavery is unjust from the fact that we sympathize not only with the fictional Eliza but with all those who really suffered under slavery. Our society can then be called just to the extent that the law reflects these general rules. When it fails to do so, the law needs to be changed. Smith was an outspoken opponent of slavery when legal systems around the globe still permitted it.

Admittedly, the role of judges is not to change the law but to interpret it. Yet every judicial opinion, if it is to be impartial, must empathetically consider the position of both sides of the case. Far from a source of bias, broad sympathies are the best protection against it. Without our ability to see the world from the perspectives of countless others and share their feelings when appropriate, impartial judgment would be impossible.

At Harvard, students and faculty alike pride themselves on their intelligence. But sheer intellect alone is never sufficient for sound moral, political, or legal judgment. We also need to cultivate a wide-ranging imagination, emotional sensitivity, and all the other empathetic capacities of the human heart and mind. There is much debate as to whether these non-rational abilities can be taught in the classroom. What clearly can be taught, however, is the tremendous importance of empathy in human life—a fact recognized by 18th-century philosophers and 21st-century neuroscientists alike.

For the past three years, I have been proud to teach both of Adam Smith’s great books to a selection of Harvard’s brightest students in Social Studies 10. Each year, I wondered who among them might end up on the Supreme Court, or even in the presidency. My hope is that, when they attain positions of power, they remember what Smith had to teach them, not only about economics, but also about empathy.

Michael L. Frazer is an assistant professor of government and social studies at Harvard University.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.