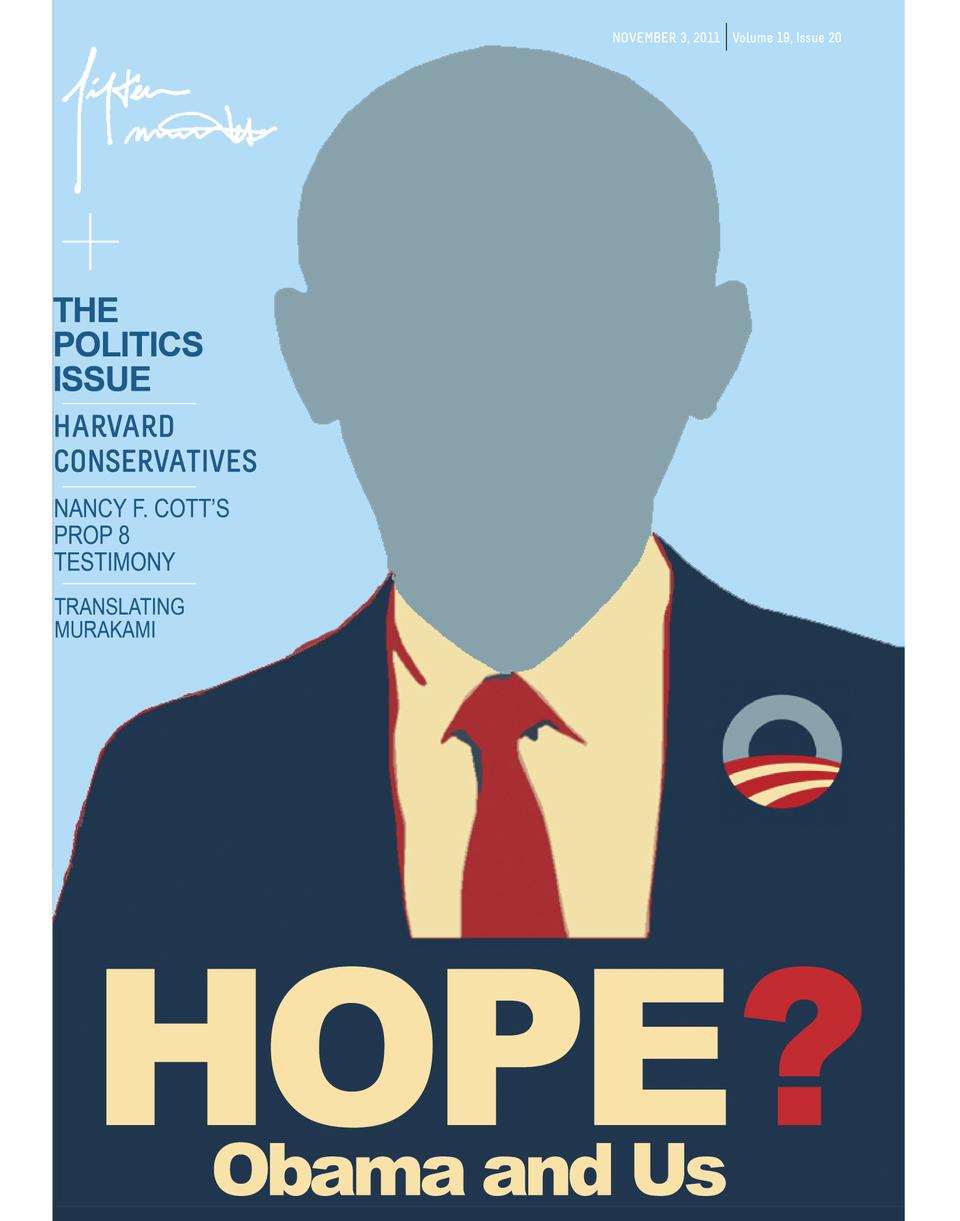

Obama and Us

Lingering around a dining hall table after dinner one October evening, a group of Kirkland seniors recalls Election Day, 2008. For Talia B. Lavin ’12, what defined that November night was the euphoria.

“We ran around in the streets, watching the election results,” she says. “I called them joy riots at the time. We stopped the traffic, jumped up on cars ...” Her friends laugh. “... OK, maybe didn’t jump up on cars.”

Anne Y. Polyakov ’12 agrees about the atmosphere. “There were lots of drunk people,” she adds.

“I was putting off my Chinese homework to watch all this,” adds Jeffrey M. Epstein ’12.

The political discussion turns to the present day.

“I think a lot of people are disillusioned with Obama,” says Lavin. “He promised to be a promoter of change.”

“He did some things ...” begins Polyakov. Lavin interrupts, “We didn’t elect him as a compromiser.”

“That might be because we misunderstood him,” Joanna Y. Li ’12 counters. “Was it possible to have done any of this right?”

“It’s hard to misunderstand hope, change,” says Lavin. “I was really gung-ho, and now ...” She trails off. The conversation stops.

It’s a natural pause in tracing the trajectory of the current president, from his 2008 campaign and election to the current state of the union. Not all Harvard students supported Obama in 2008. Not all who did are disappointed with him now. But in a Crimson poll a week before the election, 82 percent of students indicated that they intended to vote for Obama, and 11 percent that they intended to vote for McCain.

In this sense, Harvard reflects a broader national trend. Shortly after taking office, Obama had an 84 percent approval rating among voters ages 18 to 29. By this past August the figure was 52 percent. Last week, a Democracy Corps poll had the rating at 40 percent.

That things have changed is undeniable. It’s a change from which the student body has not been exempt. Three years ago Cambridge residents and Harvard students took to the streets, making traffic stop, singing the national anthem. Those who were freshmen then are about to graduate. Today, near the end of an administration, doubts have appeared about Obama in his supporters, necessitating a new way of negotiating the divide between Obama and us.

***

Lavin classes herself among the disillusioned. The 2008 election was the first in which she could vote. Initially, she saw Obama as a chance for a “clean slate.”

“During the Bush era we’d had the continual expansion of the power of the presidency, and the pretty egregious violations that came with that,” says Lavin. “There was the sense that Obama ... would actively dismantle that structure.”

To her, the structure has persisted. “I think [Obama] came in on a platform of very broad promises,” she says. Instead of making good on them, “he set about making himself a compromiser—and a compromiser in a time when the opposition is more radical than it’s been.”

Lavin is not alone in drawing this distinction: an expectation of rigid idealism set against a duller reality of compromise.

Marshall L. Ganz ’64-’92, a senior lecturer at the Kennedy School, sketches a similar portrait. “I think [Obama] promised a certain kind of presidency,” he says, “and became a different kind of president.”

Ganz, who had played a key role in developing the Obama campaign’s grassroots organizing model, diagnosed this distinction in a Los Angeles Times article published on Nov. 3, 2010, entitled “How Obama lost his voice, and how he can get it back.” In the article he contrasted Obama’s “transformational” leadership style during the campaign with a “transactional” one as president.

After the election, says Ganz, “He seemed to think that that required him to be a mediator; to be unclear about what direction he was leading in; to somehow try to create some bipartisan thing that there was no basis for.”

“He lost tremendous ground,” Ganz concludes, “not because of a specific policy failure, but because of a leadership failure—and that’s really hard to make up.”

James T. Kloppenberg, Charles Warren Professor of American History, places the blame elsewhere.

“When President Obama was elected,” says Kloppenberg, “a lot of people projected onto him their own hopes for a dramatic transformation of American politics and American culture.”

Obama was always a compromiser, says Kloppenberg, whose book, “Reading Obama: Dreams, Hope, and the American Tradition,” traces the sources of this characteristic through the people and ideas that have influenced the president. A pragmatist at heart, Obama “doesn’t believe in the existence of absolute truth”; rather, “he recognizes that you move in the direction of the truer point of view through the juxtaposition of contesting arguments.”

Within such a system, change can be only gradual, evolutionary rather than revolutionary. The lack of a clear majority of Congressional Democrats in the second two years of his first term could only prolong this interval. Young people are disappointed, then, because “they expected more from him than he was ever going to deliver,” says Kloppenberg.

“If people had known him better, they would have had more realistic expectations,” says Kloppenberg. “And if they had a more sophisticated understanding of how American politics works, their hopes wouldn’t have been as high in the first place.”

High hopes, or at least high expectations, certainly characterized the 2008 campaign. Adam B. Kern ’13, who identifies as a Republican (more precisely, a classical liberal), acknowledges that the excitement of Obama’s candidacy stemmed largely from his connection to ideas and ideals. “I did feel kind of threatened by this candidate,” says Kern. “He was promising a lot, and I was really afraid that he was going to deliver on it—there was a very real sense that he could.”

In that sense, says Kern, “I was glad to see him come down to earth.”

The same aspects of Obama and his campaign that seemed to strike a chord with many young liberals were, unsurprisingly, anathema to conservatives. “Part of the conservative scorn for Obama when he was a candidate—and he ran on this platform of change—is that it was so vague,” says Kern.

From the other side of the spectrum, Jonathan M. L. Rosenthal ’13 coincides in the feeling that Obama’s campaign was more ideological than concrete. “He represented this ideal of hopefulness and change,” says Rosenthal. “There was a sense that if he got elected it would represent a shift toward a more reasonable form of politics and away from a sort of partisan hackery.”

Instead, says Rosenthal, Obama allowed the ideal to wither through compromise in negotiations with Congress. “He started the compromise from a weaker position than he ought to have done,” says Rosenthal, “and that’s resulted in policies that at times seem more like Republican policies than Democratic policies.”

Rosenthal concedes that this emphasis may not have been a complete surprise. “He certainly talked a lot about compromise in the election,” he says, “... but on the other hand, I think a lot of people on the left still thought of him as a strong fighter for liberal policies. I think that he is not—at least he has not appeared to fight enough for liberal policies.”

As in any presidency, political grievances among the youth (and the general population) are numerous, varied, and complex. In one sense, the different versions of “our Obama” are vital in making sense of Obama as a president and of the policies of his administration. In another sense, however, who Obama is and what he stands for is less significant than how he is perceived. The American youth, the 18-29 voting bloc, saw something in Obama that they latched onto (or in fewer cases, were repulsed by), characterizations and ideals and images that he was seen as emblematizing in some presidential way. These images were always mired in subjectivity: perhaps they were justified projections, perhaps naïve ones. Perhaps the images say less about Obama than they do about his followers, disciples, and detractors themselves.

***

Peter D. Davis ’12 is less disillusioned than indignant. He finds it difficult to sit still while talking, impossible to sit while talking about politics: leaning forward, sitting back, then springing forward again. Sometimes he adds a chuckle, shaking his head, as if to show how self-evident his arguments are. At one point he cites the 2.5 million Americans who sleep in a prison every night. He brings up Woodrow Wilson, FDR, comparing and contrasting their policies and leadership styles with Obama’s. He quotes Lincoln.

Davis believes change is still necessary, and he wants to help bring it about. He is indignant because he thought Obama would enable him and others like him to “solve the great problems of our time,” a phrase he often repeats. He is indignant because he thinks this hasn’t happened.

“We had 40 years of not much happening in the country with regard to youth activism in the left,” Davis begins. He speaks with some nostalgia concerning youth involvement in the 1960s, on Martin Luther King, on sit-ins and marches. “We’re grasping at wanting to have equally big lives,” he says, “equally important lives.”

Departing from the skepticism of the previous, “postmodern,” generation, as he calls it, Davis felt that his would be “a problem-solving generation—and Obama talked about that.”

In 2006, Davis skipped school one morning to drive a group of people out to the primary, “because I thought things would be different.”

Several factors ended, as Davis puts it, “my relationship with Barack.”

Part of it is what he sees as the failure of some of Obama’s loftier campaign goals to materialize: “No attempt to restructure how Washington works, even though that was a major part of his campaign. No campaign finance reform, no ethics changes, no making sure lobbyists have less power.”

Another piece, however, has more to do with his own relationship to politics: how he fits in, or would like to.

“I get emails every week,” Davis says, “that either ask me to donate money to the [Democratic National Committee], or go out and door-knock for the midterms, or go out and donate money to Obama’s campaign.”

“All we are to them, which is all we are to any other campaign, is money and votes and boots on the ground. The number one mobilization of the president should not be to help him and his party; it should be to get us to be better citizens.”

Davis is unhappy with Obama’s presidency not only because of specific policies (he brings up health care reform: Obama’s invitation to lobbyist Billy Tauzin to the White House, after having publicly disparaged Tauzin during the campaign). He also wants to act, to enact change, on his own account. Davis sees the youth as possessing a strong potential and will for civic action: he sees Obama as having failed to tap into this current, after appropriating it so successfully during the campaign.

“I don’t want this to come off as negative,” Davis adds. “Because I’m actually more hopeful than ever that we’re going to solve the great problems of our time.”

To Davis, Obama has only a peripheral role to play in a new paradigm of change.

“In the end, we should decide to solve these problems,” he says. “Elections are one tool we can use to solve public problems ... It’s not the only tool we have.”

“We can start innovative tech startups, we can convince civic associations to solve problems.” Or, Davis says, “we can start tent cities in the middle of Zuccotti Park.”

***

On Sept. 17, some disgruntled citizens took matters into their own hands. The half-acre grounds of Zuccotti Park, originally called Liberty Plaza Park, a name some protesters are now reverting to, was quickly covered in sleeping bags and camping tents, protest signs and banners. The media attention concerning the protest has only grown, perhaps reaching a crescendo with a mass march over the Brooklyn Bridge, which resulted in approximately 700 arrests. The protests have spread worldwide, including to Boston’s Dewey Square.

Davis was there and gave a speech. Lavin performed with a student group, and witnessed the police action on the night when police arrested 129 protesters, including at least five Harvard students and alumni.

Davis cites the movement as an example of an alternative to reliance on electoral politics.

While the diversity of the Occupy movement has increased since it began, youth involvement and intensity have continued to play a central role. Yet youth participation in extra-governmental movements or protests is hardly new. For Ganz, in fact, what was striking about youth involvement in the 2008 Obama campaign was that it took place within, rather than beyond, the electoral system.

“Young people are very much engaged in movements,” he says: “civil rights, the environment, the women’s movement.”

Ganz cites Protestant theologian Walter Brueggemann, whose book “The Prophetic Imagination” points to two sources of transformational energy: on the one hand criticality, or a reasoned assessment of limits, and on the other, hope. “Young people come of age with a critical eye on the world they find,” he notes, “but with almost incessantly hopeful hearts—which means that there is an energy in youth for change and social transformation.” Criticality plus hope: for Ganz, it is a formula that has driven social movements for decades, if not centuries. It can be seen in the French Revolution; in the American civil rights movement; in the Arab Spring.

Part of Obama’s success in 2008, he says, stemmed from his ability to harness such idealistic energy, and steer it back into the political system. This energy was channeled into avenues like social networking initiatives, an army of volunteers, and a record-high voter turnout.

“Obama has a lot to be grateful to young people for,” says Ganz. But he questions whether Obama will be as lucky the second time around.

“I don’t see any evidence that that’s there again,” says Ganz. “People were clamoring to come work for Obama in 2007 and 2008. Maybe that’s happening.” He shrugs. “I haven’t heard about it.”

That doesn’t mean, however, that the transformational energy Ganz is talking about will disappear. “That energy was movement energy,” he says. Rather than fading, it is more likely to be redirected: “We’re seeing some of it pop up in these occupations all over the place.”

The “energy” Ganz discusses was an unmistakable aspect of the 2008 campaign: it was part of what supporters called hopefulness, potential for change; part of what naysayers called vagueness or lack of direction. Throughout the 2008 campaign there was much talk about the youth as a single bloc: the youth movement, the youth mobilization, the youth vote.

Ganz is one of many who doubt the continued existence of such a bloc. Many young people care passionately about a single issue, whether social, environmental, or economic, rather than about “politics” in general. What Ganz calls “movement energy” stems from a critical mass of youth involvement directed toward a single one of these issues: which in 2008, uncommonly, happened to be the election of a candidate. If the youthful energy directed toward Obama has splintered back into energy directed toward specific issues, change becomes contingent upon the experiences and opinions of individual youths, rather than upon a homogenous and indistinguishable mass.

Apart from the Occupy movement’s status as a reaction to increasing inequality and the corporate responsibility for it, the nebulousness of its demands presents, to some, an alternative to change within a political framework.

To frame the movement as an either-or scenario would be an oversimplification: no one spoken to for this article planned not to vote, and the liberal students interviewed all said they would “probably” vote for Obama. Populist protests and civic initiatives will continue to coexist and overlap with youth involvement in more traditional politics. The shift is rather one of inflection. It suggests a redirection of the transformational energy Ganz talks about: a renewed emphasis by young people on movements beyond government, rather than within it.

***

For Lavin, the Occupy Movement is “the most visible image of this political disillusionment on a massive scale, particularly for youth.”

“What really draws me in,” she says, “is the sense that a lot of the inequities that America is facing are too big to be solved by one man—by one presidency—and really are systemic.”

Lavin is not entirely convinced that the movement offers a comprehensive alternative to change within the electoral system. “I do question the efficacy of a mass movement in working out reforms of a very complex financial system,” she says.

Yet she continues to be attracted to the idealistic bent of the Occupy movement. “For the first time since civil rights,” she says, “it’s really brought back justice into the political arena. It’s brought back inequities within American society. It’s brought back issues like compassion and the social contract.”

Issues, the insinuation is, that were worthy of a recently-elected Obama but seem to be getting compromised over today. In their absence, perhaps the youth are looking for a different direction.

“Since freshman year, I’ve become a thousand times more political,” says Lavin. She smiles and qualifies: “By which I mean more informed, more willing and able to form coherent political opinions.”

She adds, “Disillusionment with the administration was part of my political education.”