News

Cambridge Residents Slam Council Proposal to Delay Bike Lane Construction

News

‘Gender-Affirming Slay Fest’: Harvard College QSA Hosts Annual Queer Prom

News

‘Not Being Nerds’: Harvard Students Dance to Tinashe at Yardfest

News

Wrongful Death Trial Against CAMHS Employee Over 2015 Student Suicide To Begin Tuesday

News

Cornel West, Harvard Affiliates Call for University to Divest from ‘Israeli Apartheid’ at Rally

Straub's 'Other People' Charm with a Wry Smile

'Other People We Married' by Emma Straub (FiveChapters Books)

There is not a single plucky heroine or Prince Charming to be found in Emma Straub’s endearing new collection of short stories about love. Her predominantly female protagonists are humorous, but Straub does not resort to the typical hallmarks of ‘chick-lit’ to entertain. Instead of having her protagonists fall over themselves in the pursuit of men, Straub makes incisive, brutishly funny observations without a trace of cloying sweetness. Consider what Amy, the young but pessimistic professor in “Some People Must Really Fall in Love” has to say about her student’s hygiene: “it got worse in the spring when the layers began to come off, like my students were twenty-five little onions, all waiting patiently to make me cry.” But despite her occasionally pungent observations, Straub’s narratives are not without heart. Without resorting to clichés or melodrama, her short stories create realistic portraits of their wry and weary protagonists. Although her characterizations are occasionally repetitive, “Other People We Married” not only satisfies, but elevates its genre through precise touches of wit and sentiment.

Straub’s talents shine brightest in three of her stories. “Some People Must Really Fall in Love” follows Amy, perhaps the wittiest of Straub’s heroines, as she deals with being passionately in love with one of her students while halfheartedly dating an older man. As seen in the other stories, Amy’s pain is beautifully, acutely detailed. The realistic, vivid ending of the story offers insight on the character’s hopeless circumstances.

In the third story, “Pearls,” Straub turns a familiar scenario—two college roommates attempting to ignore their romantic tension—into a heartfelt exploration of the raw emotions of youth. Though she draws upon stereotypes in her characterizations by endowing one of the roommates, Jackie, with more masculine attributes than the object of her desire, Franny, Straub focuses on their youth and innocence, something scarce amongst the other heroines. She allows their love to be touching but never sentimental or hackneyed.

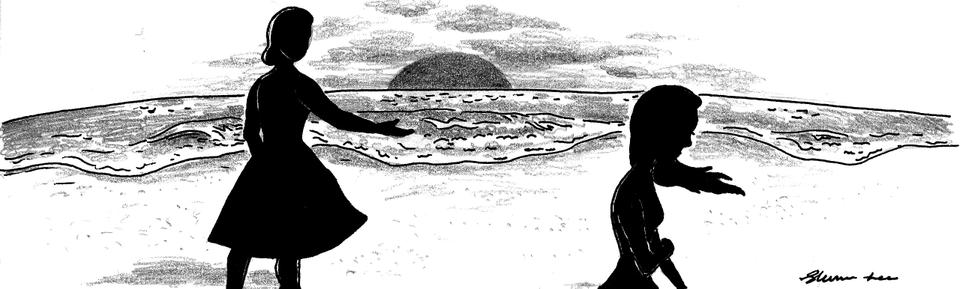

Straub applies the same precision she uses for the disappointments of her older protagonists to young Jackie’s crushing, sudden realization that Franny is unwilling to continue their romance after their brief vacation in Palm Beach. When Jackie waves to Franny, asking her to come closer to the surf, Franny stays still and Jackie thinks of “the faceless boys on Broadway, and the way that Franny would have run to them, without even giving it a second thought, just because they were handsome and tall and exactly what she’d always imagined she would have. Jackie hadn’t imagined that ever.”

The third highlight of the collection, “Hot Springs Eternal” is the only story without a female protagonist. It follows a gay couple, Richard and Teddy, as they take a trip to Colorado that will determine the fate of their tenuous relationship. Richard, the older and more sophisticated of the two, is tired of waiting for Teddy to mature. Richard has taken to closing his eyes in times of stress. His therapist calls this “taking stock;” Richard calls it “the no Teddy zone.”

Straub’s witty characters are remarkably realistic, but some are too similar to others. This restraint from exploring other types of characters sometimes weakens her writing—her continual variations on the same themes can become tiresome. In “Map of Modern Palm Springs,” two sisters with a dysfunctional relationship take a trip together, but Straub’s resistance to differentiating them produces a weak portrait of the pair. Neither of the sisters has any particularly engaging characteristics. Although they are at different stages in life, the most memorable difference between them is that one is annoyingly compliant and the other annoyingly domineering—a simplistic binary that means their bickering only irritates, even though Straub is clearly attempting to entertain.

She also chooses to revisit Franny, the girlish roommate from “Pearls,” in two other stories, showing her as a wife and a mother. Featuring Franny in other stories has the potential to add a level of sophistication to Straub’s structure. However, the conceit fails because it feels inconsistent and arbitrary—Franny is the only character that is privileged this way. The author never explores the repercussions of Franny’s relationship with Jackie, and Franny’s portrayal grows more cartoonish with age.

Likewise, though Straub’s abrupt endings normally work to her advantage, creating the tantalizing sensation that the story will continue without us, her deftness works against her in some of the stories, particularly in the extremely short “Orient Point.” This story’s melodramatic ending feels insufficiently developed, given its brevity.

By ordering her stories roughly according to the characters’ ages, Straub has made an enlightening commentary on the large and unknowable theme of love. She opens the collection with youthful characters, like Amy, the lonely professor, and Jackie and Franny. She then transitions gracefully to stories of older women—some widows, others involved in marriages that have long since passed their honeymoon stage. Examining the classic conflicts of love with fresh eyes, Straub ends the collection with the wholly modern love story of “Hot Springs Eternal.” One of the few tales with an ending more sweet than bitter, Straub’s last word is an optimistic one. Her cerebral protagonists are never destined for fairytale endings, but when Richard finds Teddy at a party after their argument, the story’s realistic, relatable resolution is just as satisfying. Teddy is wearing another man’s shirt, but Richard, in a quiet gesture of forgiveness, simply offers Teddy his own shirt and tells him to “put this on.”

Happy endings are rare in “Other People We Married,” but the poignant conclusions to each of the 12 stories complement Straub’s genuine, complex characters. This realism serves to create a nuanced, thoughtful depiction of love and loneliness in the modern world, all while avoiding the stylistic pitfalls associated with the chick-lit or romance genres.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.