News

Cambridge Residents Slam Council Proposal to Delay Bike Lane Construction

News

‘Gender-Affirming Slay Fest’: Harvard College QSA Hosts Annual Queer Prom

News

‘Not Being Nerds’: Harvard Students Dance to Tinashe at Yardfest

News

Wrongful Death Trial Against CAMHS Employee Over 2015 Student Suicide To Begin Tuesday

News

Cornel West, Harvard Affiliates Call for University to Divest from ‘Israeli Apartheid’ at Rally

Humane Fantasy in ‘Knock’

'Suddenly, A Knock on the Door' by Etgar Keret (FSG Originals)

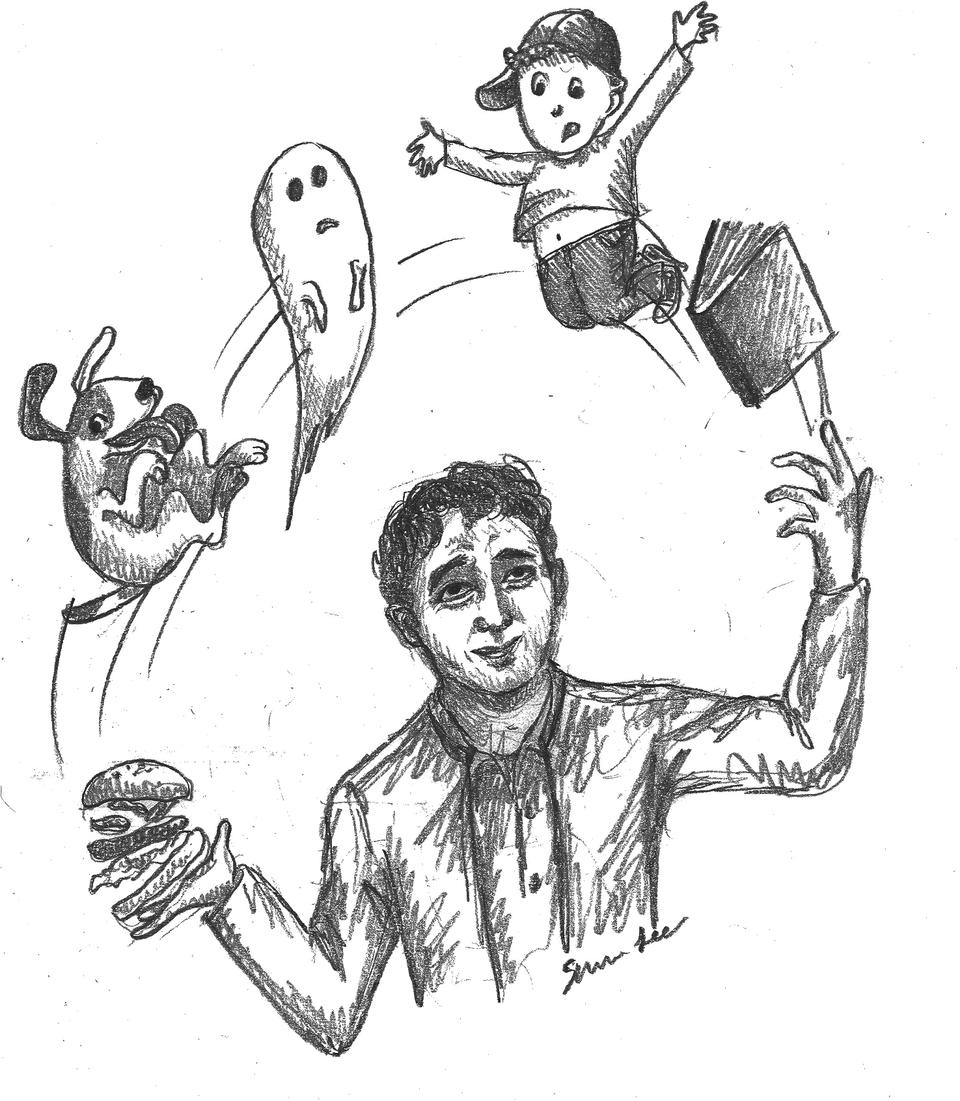

The first story in Etgar Keret’s latest collection of short stories is where it gets its title: “Suddenly, A Knock on the Door.” Three separate men force their way into the narrator’s apartment, and they demand a story from him. Despite his initial protests—that he’s a writer of stories rather than a teller—held at gunpoint, he goes on to attempt to appease them. His first story, which describes the “knock on the door” that announced the entrances of the three men, is met with disdain. “It’s exactly what’s happening here right now. Exactly what we’re trying to run away from. Don’t you go and dump reality on us like a garbage truck. Use your imagination, man, create, invent, take it all the way,” one of the intruders says. For the remaining 35 stories in the portable volume, Keret fulfills this fictional promise to use his outsized faculty for invention.

Perhaps it is this formal creativity in Keret’s writing that has led some critics to describe him as apolitical. Despite his upbringing amid the incessant polemics of Israel, his stories make only oblique references to politics. The almost flippant statement, “East is east, and west is west, and all that,” and a character snorting “contemptuously” at shekels in comparison to American dollars, are the closest things to an overtly political statement through the latest collection.

Keret’s stories are, instead, feats of pure imagination: his characters are outrageous and his plots unpredictable. In “Shut,” the narrator describes a man who daydreams so frequently that he even drives his car with his eyes closed. The story “Unzipping” shows the process of shedding a superficial identity, but in a strange and arresting metaphor. “She gently slipped her finger under his tongue—and found it. It was a zipper…When she pulled at it, her whole [boyfriend] Tsiki opened up like an oyster, and inside was Jurgen.” Halfway through the collection, the goldfish pictured on the cover of the novel is introduced as a magical goldfish who is fluent in Russian and Hebrew and who keeps a lonely immigrant company for many years.

It would be a mistake to conclude from this fantasy that Keret’s prose lacks realism or relevance. Though he refuses to adopt political positions—and though his stories can be as absurd as they are funny—they are always marked by sincerity that suggests a concrete point of genesis. “Because something out of nothing is when you make something up out of thin air, in which case it has no value. Anybody can do that. But something out of something means it was really there the whole time, inside you, and you discover it as part of something new, that’s never happened before,” says one of Keret’s many writer-narrators.

Without its grounding in reality, “Suddenly, a Knock on the Door,” would not have the emotional force that it does. In “Pick a Color,” most objects and people are ascribed an epithet of color—“A black man moved into a white neighborhood…They got married in a yellow church. A yellow priest had married them,”—and initially the trope seems childish at best. Then, a brown man kills the black man’s white wife, and the yellow priest reacts with anger towards his God. Keret writes in a “silvery God,” who shows up in person to the church, and tells the yellow priest and black man in frustration, “Do you think that I created all of you like this because it’s what I wanted? Because I’m some kind of pervert or sadist who enjoys all this suffering? I created you like this because this is what I know. It’s the best I can do.” It’s no wonder that Keret’s orthodox sister won’t let her 11 children read his works. Yet the fantasy of the silvery God is so moving because it comes from Keret’s honest sentiments.

Keret’s stories are so immediately engaging because of how strange and darkly funny they are. These characteristics though, may just be another hint of a humane social-realist impulse interwoven through the book. In “Teamwork,” when the narrator is accused of being crazy, he replies, “‘It’s not a crazy look,’ I say, and I smile at him. ‘It’s a touch of the human soul. It’s what we call feeling. Just because you have no trace of it in you doesn’t mean it’s a bad thing.’”

Perhaps Keret would agree that his unpredictable flights of fancy—whether they be in a story about a woman who only sleeps with men named “Ari,” or in a single sentence he calls “The Story, Victorious II”—are products of his all-too-predictable, sad, and shared humanity. Keret’s collection “Suddenly, A Knock on the Door” veers brilliantly away from this reality yet remains emotive and relevant.

—Staff writer Susie Y. Kim can be reached at yedenkim@fas.harvard.edu.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.