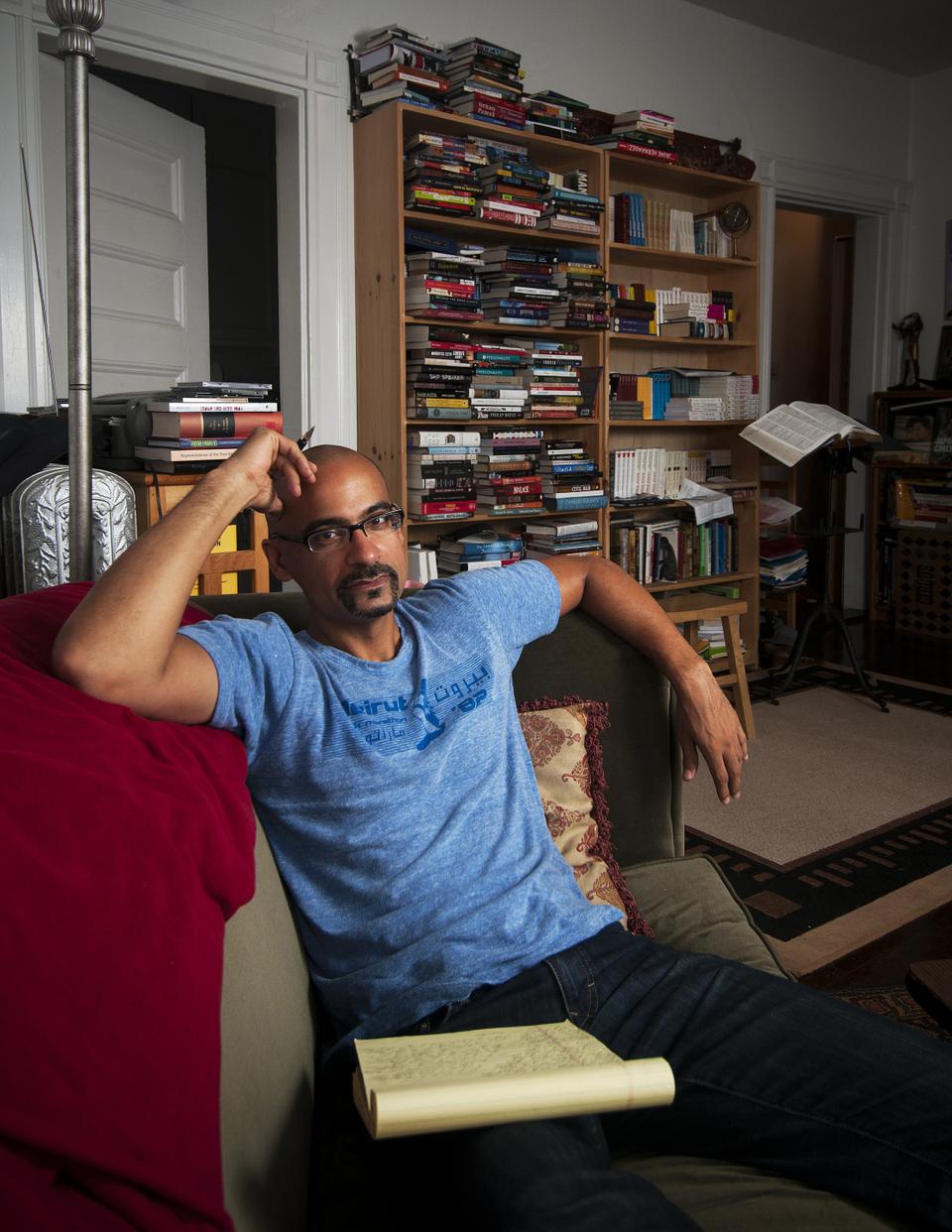

Fifteen Questions with Junot Díaz

Junot Díaz, author of “The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao” and “Drown,” meets me in front of the Harvard Bookstore. It’s 9 a.m. on a Friday, and the early September humidity is just beginning to spike. Díaz is wearing a mottled red t-shirt, dark grey jeans, running shoes, and a Boston Red Sox cap. He kisses me on both cheeks when we meet. Recovering from back surgery, Díaz finds sitting almost impossible so we begin walking down Bow Street towards the Charles River.

Fifteen Minutes: You did an interview with The New York Times recently and talked about many of your favorite books. It’s an impressive list—how do you find time to read all of those authors?

Junot Díaz: You have to understand: It’s what I do. When something is really important to you, I think you’re always looking for an excuse. I find reading more important to me than almost anything, including my writing. I consider myself a reader way more than I consider myself a writer. Perhaps what might have struck anybody about that interview was that this quantity of reading is more emblematic of the way I organize my life than anything.

FM: Did you read anything before we met this morning?

JD: Before I came here I read a chapter of a book on invasive species while I had my damn oatmeal, and I said, “I could have my fucking oatmeal and just chill. Or, I could put in 25 pages.” And so 25 pages are done. The book will be done by this evening because I sort of use these still, interstitial moments to burn through them. My favorite line of the chapter was the last line: “It is unlikely that anyone will ever again enter New Zealand carrying a red deer.”

FM: There’s one line that really struck me from a short story you wrote titled “The Cheater’s Guide to Love.” The line was: “The half-life of love is forever.” Can you explain that to me?

JD: I think you discover something—perhaps some of us discover it young, perhaps some of us discover it much older. You can get over a person romantically and never fall out of love with them. As a young person I had no idea that that was possible. I always thought that eventually a relationship would come to end, and your imaginary would find in time surcease. But I think when you really fall in love, there seems to be something permanent that happens to you.

FM: What do you think is that permanent change?

JD: Perhaps whatever insight the story was making is not particularly axiomatic. Perhaps it’s just something idiosyncratic about me. But it certainly feels that way when I stand and look back at all my relationships, beginning to understand that there are a few of them that never seem to diminish, neither in my mind nor my heart. You just manage them.

FM: A powerful idea.

JD: Love reveals us. Profoundly and unnervingly, love reveals us. I think this is something that can often be a source of comfort and dismay. Most of us are not used to being naked. And I can’t speak to the world, but that first time you disrobe—the first time you disrobe before someone you care about—shrinks in comparison to the first time you begin to unveil your internal self. What I think of the stories that I was overwhelmed by growing up, that astonished me growing up, I think they always drew upon that notion of how we are revealed in love.

FM: When did love stories first begin to captivate you?

JD: I was always one of those kids who was aware from an early age that there was a narrative partition along gender lines. I was aware that love stories were supposedly the bailiwick of girls, and adventure stories were supposedly the bailiwick of boys. Now, we know fundamentally that this is a lie. We also know that these kind of hierarchical dichotomies do a lot of oppressive ideological work. So as a kid I was always attracted to stories that I was told were somehow not pertinent to me.

FM: What were some of your favorite love stories growing up?

JD: So of course you know, standard English reader, the towering work of both a fictional bildungsroman, but also one of the great love stories of our language: “Jane Eyre.” There was also something far nerdier, but that came up at the same time. Most people never imagine children’s cartoons to have really good stories about love that are sophisticated and complex. And there was when I was growing up this anime that they were showing on TV. And I was a kid, man. This anime was called “Robotech.”

FM: What did the characters from these stories teach you?

JD: Sometimes the right choice is also the hardest choice. Often, most of us choose for safety. I think it is easier to go to Mordor bearing the ring of the enemy than to advance into the unknown wilderness of another person’s heart.

FM: Are most of the stories in your new collection “This is How You Lose Her” about love in some way?

JD: Love and its consequences. It’s really a book about the rise and fall of a Dominican male slut. How did the boy learn to be a male slut, or at least this particular boy? How he is formed, and how that formation undoes him in the end. Because one must reflect that many of the messages we labored under were piercingly contradictory.

FM: How so?

JD: On the one hand, we’re told that the sort of proof and excellence of a man is measured by how many girls he can get, by his lack of vulnerability, by his indifference and often his hostility towards what would be considered traditional women’s arenas: domesticity, love, familial bonds, nurturing, family. And then there’s the other side which is: Who the fuck can be whole, who the fuck can be human without intimacy, without encountering that profound terror that we call love? On the one hand, you’re being told that that shit doesn’t mean shit. That that shit is shit. And on the other hand, your heart is dying for it. And it’s not as if boys are victims. Boys, believe me, profit quite well from the patriarchal, heteronormative arrangement. But, on the other hand, there clearly is a price to be paid for being a loyal boy. I think it’s really, really interesting how we doubled down on our bullshit because we didn’t have anywhere else to go. If I get more girls, maybe I’ll feel better. If I’m more of a masculine prick, maybe I’ll feel better. Maybe you just dig yourself deeper into a hole.

FM: How did you begin to dig yourself out of this masculine hole?

JD: I’m an artist. I kind of was already vulnerable to vulnerability. And I had fucking awesome women in my life. I went to Rutgers, and it was the best time of my life. I was such a moronic fool. I still remember once saying right at the beginning of my tenure at Rutgers, raising my hand and asking our teacher, an avowed and passionate feminist, why we were reading so many women. The beatdown from my female classmates was thorough, sustained, and merciless. It was fucking great. I can still hear the blows in my head from their genius. And yet, I think that without those blows I would never have become an artist. But, man, what a struggle with self. I was a moron for a very long time. It’s like being an asshole—if the show only runs five seasons, being an asshole for four and a half.

FM: So you don’t consider yourself an asshole anymore?

JD: Oh, of course I do. That never goes away. Come on, one doesn’t let oneself off the hook that easily. I think that it’s not the situation where one is transformed, where one is instantly converted and the conversion sticks. The truth is that you manage that shit. But that shit doesn’t fucking go away—that’s why I think it’s sort of dishonest when dudes are like, “I’m a feminist.” I’m not certain if, given all the training we’re given, men can be feminists. I believe myself a feminist ally, but a feminist? I think it would be possible only when we have the matriarchal revolution we’re all dreaming for.

FM: Do you think there will be a matriarchal revolution?

JD: Well, I mean, what the fuck are we around for if there’s no hope for that? Do you want to see this shit go on for another fucking 40,000 years? Look at this fucking nonsense. I mean, honestly. My shit isn’t that somehow women are transhuman, that their essence is morally, ethically superior. My thing is, “Okay motherfuckers, we’ve been at this game now 40,000-plus years depending on how you rank Homo sapien civilization.” I think it’s time for a time out. For real. Dudes could use a 10,000-year time out, minimum.

We cross Mass Ave., halfway between Harvard and Central Squares, then wander up Harvard Street. Díaz lives a handful of blocks away.

FM: Why do you live part-time in Harlem and part-time in Cambridge?

JD: New York is home in ways few places are. I feel like I have Jersey and the Dominican Republic, and they come together in New York City because New York has about a million Dominican immigrants. When I want to get midway to Santo Domingo, I’m in upper Manhattan, so that’s where I live.

FM: So why the Red Sox hat?

JD: I’m a Mets fan, so there’s no contradiction. And I’m Dominican. And you gotta remember that the Boston Red Sox, for a long time, has been the second Dominican national team. The only reason the Red Sox won their rings was because of fucking Pedro, was because of Manny, was because of D. Ortiz. And those are all Dominican players. So we, as a sort of a national identity, were rooting for these boys because they were our boys. They were the height of our athletic prowess. But no, I’m a Mets fan, and fucking the Mets, man. The Mets. You want to talk about a fucking eternal battle with failure? There you go.