News

Cambridge Residents Slam Council Proposal to Delay Bike Lane Construction

News

‘Gender-Affirming Slay Fest’: Harvard College QSA Hosts Annual Queer Prom

News

‘Not Being Nerds’: Harvard Students Dance to Tinashe at Yardfest

News

Wrongful Death Trial Against CAMHS Employee Over 2015 Student Suicide To Begin Tuesday

News

Cornel West, Harvard Affiliates Call for University to Divest from ‘Israeli Apartheid’ at Rally

As Investor Interest in Allston Grows, Opportunities for Prospective Homeowners Dwindle

A little over a year ago, then Brighton resident Paola M. Ferrer was preparing for another disappointment in her search for a home in Allston.

For at least the seventh time over a span of six years, Ferrer had fallen in love with a property in North Allston, the largely residential community north of the Massachusetts Turnpike in which most of Harvard’s land lies. The previous properties had all been scooped up by investors paying in cash before Ferrer could even make an offer, leaving her “heartbroken.”

Realtors, brokers, and friends told her that at her price point she could afford a much bigger home in other neighborhoods and towns in the Boston area. Ferrer, however, could not give up on Allston, she said.

“I felt I was really building community here,” she said. “It was important for me to stay here.”

Ferrer’s perseverance ultimately paid off. After a six-year search—juggling student loan debt, strict housing loan regulations, and the expiration of the contract at the apartment she was renting—she closed on a condominium in North Allston last spring.

“The universe just kind of aligned all of these pieces, and I was able to do it,” she said.

The obstacles Ferrer faced were not unusual, according to Carol Ridge-Martinez, the executive director of the Allston Brighton Community Development Corporation, an organization that creates affordable homes, educates first-time home-buyers, and fosters community leadership.

In recent years, Allston’s location near three large universities—Harvard, Boston University, and Boston College—has compounded the difficulties potential Allston homeowners face. As these universities expand and develop, they alter the housing environment in the neighborhood.

Residents say that cash-paying investors seeking to rent out properties swoop in and purchase newly available houses before potential homeowners have the chance to make a bid. And they worry that the influx of transient students that these investors market the properties to threaten the family-friendly character of Allston, forcing out lower-income families and decreasing the quality of the neighborhood’s housing.

TRIPLE-DECKER

Over the last ten years, and especially since the recent economic recession, Allstonians have faced the same difficulties in the housing market that have plagued many Boston communities.

Jessica B. Robertson has lived in Allston for ten years and two years ago started looking for a home to buy in North Allston.

“Almost nothing is coming on the market,” she said, adding that the units that do are often out of the price range for young people looking to buy their first home. In addition, Robertson said that community members are growing concerned over the increase in rental prices, the median of which spiked over $300 between 2009 and 2012, according to annual reports by the city of Boston.

Allston residents said that the dearth of available housing as well as rising rental prices can be traced in part to a trend of investors purchasing homes, dividing up the units, and renting them out to populations willing to live in groups, such as university students.

These investors buy up properties—increasingly single-family homes—with cash, making it very difficult for prospective homeowners to be competitive, Ridge-Martinez said.

Buying single-family housing in Allston had not traditionally been cost-effective for investors, making these properties accessible to prospective homeowners such as Ferrer and Robertson, Ridge-Martinez added. But an influx of 20- to 35-year-olds to Allston who are willing to live together and split up rents has made buying up single-family homes a much more lucrative investment in the neighborhood, she wrote in an email.

According to Melina A. Schuler, a spokesperson for the city of Boston, the switch to an investor-owned model was precipitated by the recent recession. Residents who owned their triple-decker homes were hard hit by the foreclosure crisis and often sold their buildings to investors. The recession-induced trend intersected with another, longer term shift in the Boston real estate market that has seen Boston become a center for investment in the last decade, especially for international investors, who approach sellers with cash.

Allston is especially attractive to investors due to Harvard’s expansive development of North Allston over the next decade and the high student demand from BC and BU for off-campus housing, according to Brian Swett, chief of environment and energy for the city of Boston. The neighborhood is relatively cheap and convenient, compared to others in Boston, for students hoping to live off campus, according to annual reports on median rents by the city of Boston.

Though these trends have brought Allston an occupancy rate higher than any other neighborhood in Boston, many Allstonians say they are concerned that rental units catering exclusively to students could lead to a community of mostly transient populations who never settle down in Allston.

“It is important for neighborhood stabilization for renters like me to find a home and be able to stay,” Robertson said. This is difficult when landlords market properties to groups of students, instead of young renters looking for a more stable community, she added.

“So long as we continue to have a very short-term renting situation, it’s going to be really difficult to get people to take some pride in the neighborhood or get involved,” Ferrer said.

INVESTMENT BUZZ

These community concerns arise within a neighborhood that is growing and changing demographically. The population of Allston grew 14 percent between 2000 and 2010, a growth rate almost three times that of the City of Boston as a whole, according to U.S. census data compiled by the Boston Redevelopment Authority.

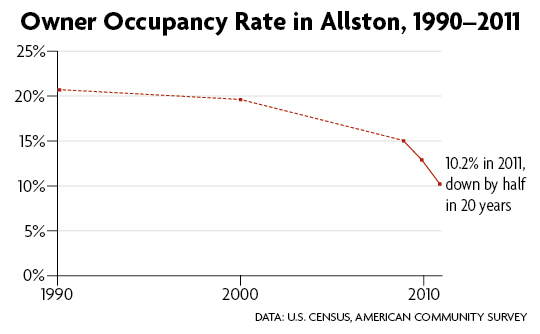

Swett said that the housing stocks of many neighborhoods in Boston, including Allston, have switched to investor-owned models. Only 10.2 percent of housing units in Allston were resident-owned in 2011, down from 15.0 percent in 2009 and 19.6 percent in 2000, according to census data compiled by the BRA. Swett estimates that number is even lower today.

He also noted that as of 2010, 75 percent of investor-owned property in Allston-Brighton were triple-decker homes, which have traditionally been family-owned.

Ridge-Martinez attributed gentrification in Allston to a general increase in interest in urban living as well as to the allure of Harvard’s development in the neighborhood, among other forces.

“The buzz of Harvard’s master plan is very attractive to a lot of people,” she said.

Harvard has embarked on a ten-year institutional master plan in North Allston that will include 1.4 million square feet of new development and 500,000 square feet of renovations.

The projects within the IMP will parallel construction of a science complex on Western Ave. that will house the engineering school and a mixed-use development at Barry’s Corner including both residential and retail space that broke ground last December. Ridge-Martinez said that these development plans have played a role in driving increased investment interest in neighborhood properties.

Allston resident John Eskew similarly described the effect of Harvard’s development in Allston.

“Developers try to get ahead of that wave and that definitely drives up prices and pushes out the working class people,” he said.

With prices increasing, Ridge-Martinez said that the city and organizations such as the Allston Brighton Community Development Corporation must develop strategies to allow lower-income families to stay in the neighborhood.

“We have a vision of Allston-Brighton as a mixed-income community,” she said. “Can we keep a placeholder for maintaining some of the character of the community?”

FINDING A BALANCE

While community members and city officials largely agree that the changes to Allston’s housing stock are eroding the cohesion of the community, a variety of strategies for addressing residents’ unease have been proposed involving both the city and the universities flanking the community.

“The community does not resent the students for living here,” Allston resident Richard Parr ’01 said. Instead, he said, homeowners and other residents are frustrated by absentee landlords who split up properties for transient populations and neglect their units.

Both Allstonians and city officials said that universities in the area have a responsibility to increase housing for their students. Students from BU and BC make up the majority of students renting in Allston, as Harvard students currently tend to cluster across the Charles River in Cambridge.

“The city of Boston has an interest in making sure universities provide as much on-campus housing as possible,” Swett said, adding that the city is working with universities both to promote on-campus living and to get information about where students are living off-campus to prevent overcrowding.

Swett also pointed to the Dec. 2012 establishment of a chronic offenders registry for Boston landlords who fail to correct issues on their properties as a recent development in combatting negligent landlords. Those on the registry, which is still in development, are subject to heavy fines. Swett hopes that universities will advertise the registry to their students once it is opened and in so doing help alleviate the most egregious problems with landlords.

Allstonians also noted the need for a strong city response to negligent landlords.

Allston resident Matthew Danish noted that community members were pleased with an new inspection program that went into effect in January. The program requires property owners to register unoccupied properties with the city and pay a $25 registration fee per property, with property inspections once every five years. Though some landlords claim the program is a burden, Danish sees it as the city “stepping up inspection services” and helping those in need.

Allston residents often emphasize the potential for development on the vast tracts of Harvard-owned land in North Allston, especially the undeveloped property along Western Avenue, for commercial and residential purposes.

“Harvard has a lot of vacant land at a time when there’s a desperate need for housing,” Robertson said, adding that the community was very pleased with the Barry’s Corner Residential and Retail Commons, where the University partnered with a private developer to build private housing as well as retail space.

The University included a $3 million homeownership stabilization fund in its community benefits package to Allston. The package is part of Harvard’s institutional master plan and was approved last November by the Harvard-Allston Task Force, an advisory board the BRA has charged with acting as a liaison between the neighborhood, the city, and the University.

For her part, Brigid O’Rourke, Harvard’s communications officer for University planning and community programs, wrote in an email that Harvard and the BRA are still crafting the specific details of the cooperation agreement that includes the fund, which will be managed by a third-party organization.

“Community members recognize that there are no easy answers,” Danish said, even as the University and the city have begun to confront Allstonians’ concerns over the changing nature of the neighborhood’s housing stock. The extent to which Harvard’s development will bring other real estate developers to Allston also remains to be seen and emphasizes the uncertainty of the future of the patterns that worry residents, he added.

In the meantime, for prospective homeowners looking to buy in Allston, the struggle to compete with investors’ deep pockets is unlikely to change.

—Staff writer Karl M. Aspelund can be reached at karl.aspelund@thecrimson.com. Follow him on Twitter @kma_crimson.

—Staff writer Marco J. Barber Grossi can be reached at mbarbergrossi@thecrimson.com. Follow him on Twitter @marco_jbg.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.