News

Cambridge Residents Slam Council Proposal to Delay Bike Lane Construction

News

‘Gender-Affirming Slay Fest’: Harvard College QSA Hosts Annual Queer Prom

News

‘Not Being Nerds’: Harvard Students Dance to Tinashe at Yardfest

News

Wrongful Death Trial Against CAMHS Employee Over 2015 Student Suicide To Begin Tuesday

News

Cornel West, Harvard Affiliates Call for University to Divest from ‘Israeli Apartheid’ at Rally

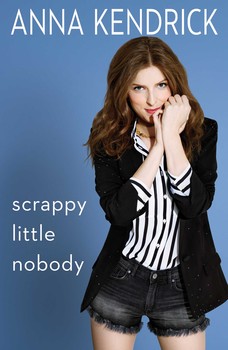

‘Scrappy Little Nobody’ Fresh and Authentic

"Scrappy Little Nobody" by Anna Kendrick (Touchstone)

Anna Kendrick, star of “Into the Woods” and “Pitch Perfect,” recently joined the growing club of celebrity authors with her debut memoir, “Scrappy Little Nobody.” Her edgy wit and instinctive sass (her Twitter account is living proof), however, beg to be recognized in their own right, separate from the world of ghost writers and self-admittedly semi-literate A-list actors. Still, is she ultimately just another celebrity posing as a novelist?

Kendrick is obviously not a writer: Odd attempts at wisdom close chapters of random anecdotes, sentence structure is often overly simplistic, and an outside hand (or thesaurus) seems to have thrown in obscure words in an attempt to refine the tone, making for some choppy passages and transitions. But these imperfections of her writing, along with her unabated candor and relatable frustrations with friends, boys, and money, make her memoir true to her and her voice. It overall succeeds in its purpose to humanize Kendrick as just a “normal” person, one who still gawks at the price tags of shoes, hides stains under rugs, and likes boys who don’t like her back.

She writes her memoir through a collection of autobiographical essays, starting with her childhood. With disclaimers that she is “not kool“ and “a very, very small weirdo,” she sets a consistent tone of playful self-deprecation. However, these initial chapters comprise the weakest part of the book. Her sarcastic interjections, meant to poke fun at the inevitable awkwardness that is adolescence, interfere with the content of her stories, which itself is interesting. When she recalls her experience playing Tessie from “Annie,” for example, she interjects, “We sang ‘It’s the Hard-Knock Life’! We did a dance with tin buckets and scrub brushes that was bursting with adorable scrappy rage! We got to embody the rollicking fun of being orphans!… So maybe I still had too much energy—they’re adding a TAP number?! Let’s go learn it!” Perhaps her humor does not deliver on paper as desired, or she attempted to match the immature banter of childhood (albeit with an abundance of expletives), but either way, her stories would have fared better without the added commentary.

But the beauty of her stories is Kendrick’s ability to normalize otherwise esoteric situations. Yes, she had an agent and a full-time acting job at the age of 10, but she also cleverly conveys both her unusual boldness at school and her normalcy among “crazy child actors”—a relatable sense of feeling different and not quite belonging. At age five, she got her start in acting when she performed a Shirley Temple classic at a recital but forgot the lyrics halfway through, stoically concluding to her mom, ”Well, that was stupid.” As she navigated the theatrical world full of “freaky” child actors—including a boy who complimented her name for its “syllabic symmetry”—she developed an aversion to precocious humble-braggers and arrogance. Her dislike of vain entitlement persists: After defending that she went to Payless to buy “respectable shoes” when she was 10, she apologizes, “I have been around rich people too long, and it has made me defensive.” Moving from theater to a movie career—a transition that could’ve used more explanation—her new celebrity status did not go to her head. Even as she donned thousands of dollars of diamonds on her neck, she still came home to a “squalid” apartment with Ikea furniture. She describes her double-life: “I grew more fearful that my filthy secret would spill out: I am—at best—a normal human, and this has all been a misunderstanding. A lot of people were devoting a lot of energy to maintaining the illusion that I was the ready-made ingenue. It made me feel disingenuous and guilty. I was participating in a con.” Here was a “normal” person who had somehow found her way to fame and was expectedly confused but was, in the public eye, just another celebrity.

Her fears of being “discovered” seem to stem from her intriguing attempts to cling to her humanness and all the struggles and mistakes that come with it. She writes, “I want to be a real person, even if that person wasn’t so great to begin with. I want to always be able to say, Hey, I’m not incompetent because I got famous, I’m incompetent because I’m a pathetic waste of humanity.” Thus, her memoir gives a glimpse of the diversity of the celebrity experience as she faces the repercussions of her own fiery independence and refusal to succumb to the norms of fame, including “being nice.”

Readers shouldn’t expect nor be disappointed by the lack of “good” writing, because in short, Kendrick is not a writer, nor does she pretend to be one. It is her alacrity to show herself in a realistic light that differentiates this book from the genre of celebrity glamor. Her final chapter, a satirical take on book club questions, epitomizes the interactive and lively nature of her book overall. The last question reads, “Anna makes a lot of bad decisions. Can you think of a time when you’ve made a bad decision? Oh wow, really? We’re gonna pretend you can’t think of a single example? YOU THINK YOU’RE BETTER THAN ME?!”

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.