News

Cambridge Residents Slam Council Proposal to Delay Bike Lane Construction

News

‘Gender-Affirming Slay Fest’: Harvard College QSA Hosts Annual Queer Prom

News

‘Not Being Nerds’: Harvard Students Dance to Tinashe at Yardfest

News

Wrongful Death Trial Against CAMHS Employee Over 2015 Student Suicide To Begin Tuesday

News

Cornel West, Harvard Affiliates Call for University to Divest from ‘Israeli Apartheid’ at Rally

El Pueblo Unido

“For 300 years she has been a slave, a force of cheap labor, colonized by the Spaniard, the Anglo, by her own people (and in Mesoamerica her lot under the Indian patriarchs was not free of wounding)”―Gloria Anzaldúa, “The Wounding of the India-Mestiza”

Ruben: I do my own laundry. It’s tempting to pay HSA to do it for me, but it’s an expense I can’t justify to myself. In one of my first weeks in Leverett, as I was bringing two weeks’ worth of dirty clothes to the laundry room, I heard a surprisingly familiar Spanish drawl. It carried the way my abuelita’s words carried through her adobe house in rural El Salvador. It sounded like my tios and tias gossiping around a table at one of countless family cookouts, their words finding a rhythm with the sizzling of pupusas cooking in the background. In my dorm that day, thousands of miles from home and even further from El Salvador, the words came from a conversation between a cleaning lady and a maintenance man. Their Spanish was distinctly Salvadoran.

Zoe: Sometimes, I feel lost. It’s as though I’m on this impossible quest attempting to find something that reminds me of home. I’m constantly seeking out the hints of color in the otherwise blinding sea of white, because when the cold sets in and I’m reminded of how far away I am from home, I just want the comfort that comes from those moments of familiarity. I was walking out of a section for my Social Studies class when beautiful, lilting Spanish words immediately transported me to images of the paleta man coming down the street, hardworking brown bodies, and food so spicy that water can never be very far away. I turned the corner and found the source in two of Mather’s Latinx custodial workers joking and laughing with each other. The familiar sounds of rolled r’s and rapid-fire words fell from their lips, providing me with a warmth I fail to find in predominantly white syllabi and classrooms where the moments I find a face that looks like my own are few and far between.

R: I saw myself and my family reflected in them. And this wasn’t the first time I’d found myself reflected in my university’s labor force. Many of the Harvard University Dining Services staff are brown and black people, and, in their accented English, it isn’t too difficult to hear my father and mother when they first moved to the United States. When the HUDS workers went on strike last fall, I joined the picket lines and demonstrations not only because healthcare and living wages are human rights, but because they are rights I wanted for those who feel like family. Chanting with HUDS felt like Sunday morning sermons, and, in rallying with them, I felt amongst family again. University administrators try to create a sense of home for incoming students, but exchanging hellos with the labor staff feels more like home than most classrooms and student organizations.

Z: Home is a place filled with people of color, inside of Houston where the signs and advertisements are just as likely to be in Spanish as English. It is the joy I felt when I was wearing my Harvard Latina shirt and one of Mather’s HUDS workers pointed at it and told me she loved it, because she was a Latina, too, a Dominicana, and proceeded to make me feel as comfortable as she could. Yet the reminder that my roots are in stark contrast to those of the majority of Harvard students came in the form of conversations centered around the strike, when a girl told me that she just couldn’t quite understand why the HUDS workers were striking. Didn’t they know, she proclaimed, “that certain jobs just make certain wages?” I felt sick. Her words haunted me as I yelled “Harvard, escucha, estamos en la lucha,” as I became a part of the we, a we dominated by faces with skin painted a color so similar to my own, nuestra comunidad.

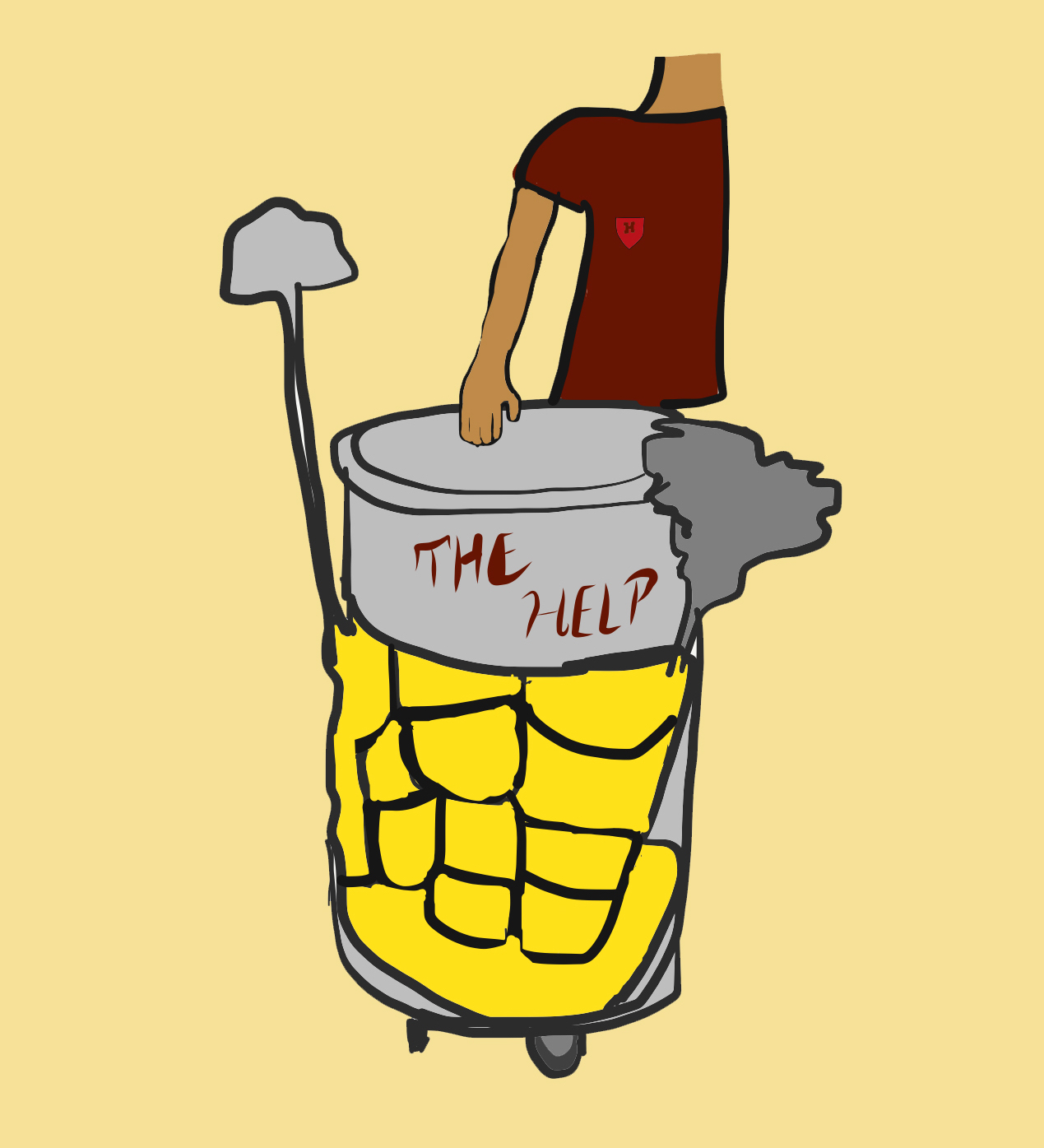

R: And when people disrespect labor staff, by leaving their trays in the dining hall or not cleaning up their puke after a night out because they know a brown body will come in the morning to clean, it feels painfully personal. When people opposed the strike on principle, failing to see the HUDS staff’s humanity, it felt like a denial of my own humanity. When my peers ignore labor staff, it feels like they could just as easily ignore me in the classroom. And given that in 2014, only 14 percent of FAS executive, administrative, and managerial jobs went to minorities—compared to 61 percent of maintenance and service jobs—it makes sense that students would associate brown skin with nothing but labor. It’s a narrative fed to us by movies and television shows, and the vast underrepresentation of Latinx individuals in most major professional careers. Fixing the issues of misrepresentation and underrepresentation benefits all Latinx individuals, regardless of the socioeconomic background from which they come.

Z: We were fighting. Fighting a Harvard, a world, that said that we deserved to make “certain wages” because we were in those “certain jobs.” I wondered if that girl would have sung a different tune if she could see her community reflected in the brown hands roughened from serving the privileged students at one of the most prestigious universities in the world. If she could see her roots reflected in the eyes of people who were in some way the products of a hope for a better life, only to be forced to fight for the basic right to affordable healthcare and more than just the “certain wage” that the privileged have deemed nuestra communidad worthy of receiving.

R+Z: Disrespect towards staff members, or disregard for their livelihood, shouldn’t be tolerated, regardless. Compounded on the way that we relate and hear ourselves in the Spanish staff speak, it becomes an attack on your peers as well. We constantly claim to strive for a campus community that is inclusive of all, regardless of ethnicity or background, but until we start acknowledging labor staff as part of that community, students of color will continue to struggle to feel fully included.

Ruben E. Reyes Jr. ’19, a Crimson editorial chair, is a History & Literature concentrator living in Leverett House. Zoe D. Ortiz ’19, a Crimson editorial executive, is a Social Studies concentrator living in Mather House. Their column appears on alternate Mondays.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.