News

Cambridge Residents Slam Council Proposal to Delay Bike Lane Construction

News

‘Gender-Affirming Slay Fest’: Harvard College QSA Hosts Annual Queer Prom

News

‘Not Being Nerds’: Harvard Students Dance to Tinashe at Yardfest

News

Wrongful Death Trial Against CAMHS Employee Over 2015 Student Suicide To Begin Tuesday

News

Cornel West, Harvard Affiliates Call for University to Divest from ‘Israeli Apartheid’ at Rally

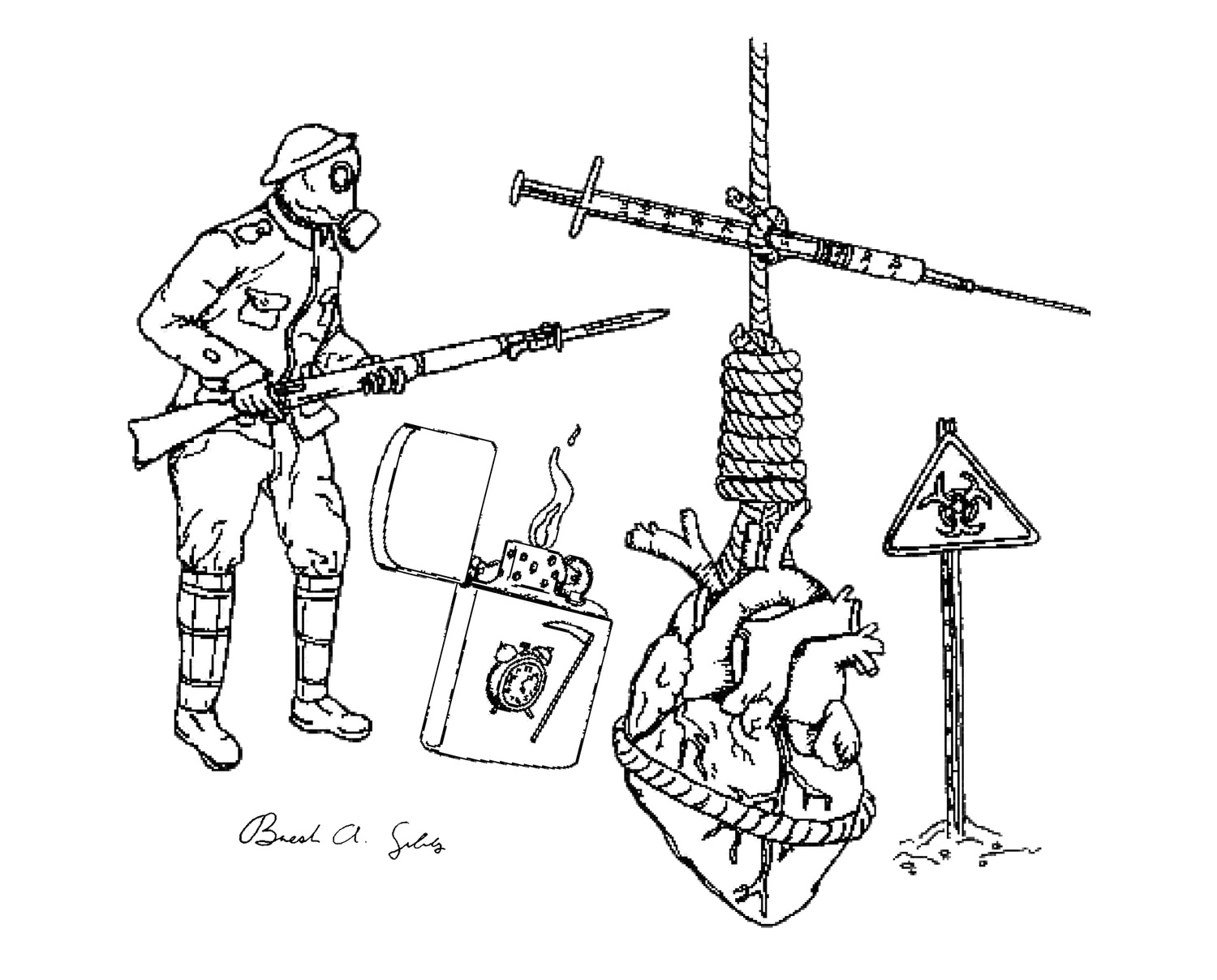

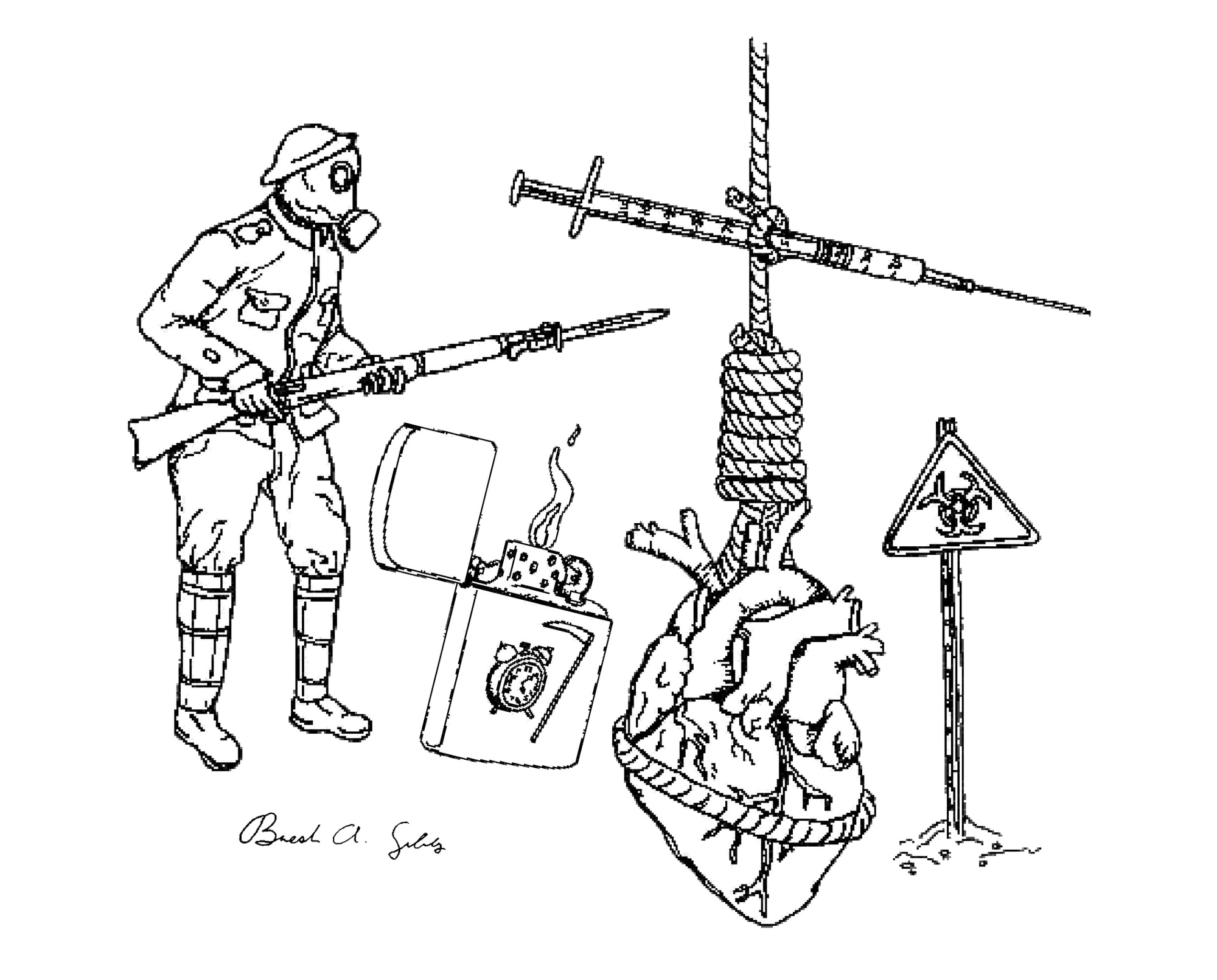

Before I Wake

Thirteen ways to die and why they require your attention

If I should die, I want my death to be as glorious as life. I want to be swung up in flung fate on the brink of a car crash, shifted in the blank air like broken glass. I want to be the oldest person on earth. I want the knife pointed at my throat. I want to protect something devastatingly right. I want it all: elegies, rhapsodies, tears, news clippings, and those wicked laughs in the backroom. I want my body folded wrong; I want destruction for construction. I want to die from Pop Rocks and Coke. I want to die next to someone I’m desperately in love with. I want to have known that person for three days. I want to have known that person for 70 years. I want to do it like Svidrigailov. I want to grow old. I want to dream up heaven, and I want it to look so much like a Greek mansion that even Athena hides in the kitchen. I want to encompass death, to wear it on my sleeve or keep it under my skin, because, well, if you can’t find something to live for, you sure should find something to die for.

That paragraph was blunt. I wrote it with abnormal, un-conversational conviction. I wrote it to both glorify and qualify, to make death as close as breath. I wrote it in a world where the dead do not die but pass away, kick the bucket, depart this life, meet their maker. Where death is often viewed as dark. Where death in the media takes form in ghosts, zombies, and other members of the supernatural more often than not. Where death seems unnatural and deviant, something too far to touch.

But there is no other controversy like death, like Michael Brown’s blood oozing onto the streets of Ferguson, like Trayvon Martin’s and Walter Scott’s and Brendon Tevlin’s and so many others. There is no other market like death, like medicines meant to expand lifespan, like the fountain of youth, like the funeral industry. Americans hate death. Americans love death. While some accuse Americans of erasing and denying it, others accuse them of glorifying it. While some view suicide, especially that of young people, as a catalyst to reevaluate cultural kindness and societal values, others accuse those who do commit suicide, even Vincent Van Gogh or Virginia Woolf or Robin Williams, for not thinking long enough to find a reason to live. We deal with death by “forgetting it.” We deal with death, even with national tragedies, by “getting over it.” Or we don’t deal with death. We love to live. In too many ways in American society, death, unlike life, isn’t individually practical, isn’t profitable, doesn’t have potential to get a college education or raise a family, doesn’t have any potential, period.

But death is real. Some psychologists claim that conversations about mortality will become increasingly important over the next decades, as America’s largest generation, the baby-boomers, die off in unprecedented numbers. As Dr. Lawrence R. Samuels wrote in an article in Psychology Today, “I…conclude that the emerging ‘death-centric’ society will be a period of considerable turmoil, perhaps equivalent to that of the countercultural 1960s and 1970s.” Though I don’t think about death in such overarching, dramatic social terms, I understand that if understanding death is not sociologically important, it is personally, even if not politically, essential.

We should think about death as brilliantly and deeply as we think about life. We should think about how we want to die as much as how we want to live. Because the world is made up of counterparts and opposites, yin-and-yang and complementary colors. My high school English teacher believed that Javert could not exist without Jean Valjean, that Razskolnikov did not have meaning without Svidrigailov. The cliché states that you can’t know happiness if you don’t know sadness, that there is no male without a female. Understanding both, a topic and its opposite, deepens the meaning of both. So it is strange to believe that we can live life meaningfully without thinking of the nature of death incessantly; it is strange to think we can live if there is nothing to die for, or that we can live long enough to forget the impact of death and grief, that we can chase death away further by taking the right, precautionary steps to live.

Question death because it holds life. Glorify it. Grieve it. Love it. Hold it. Hate it. Want it. Watch it. Because there are so many truths in these statements, so much bubbling under the surface. So much to know about those who want to grow old, who want to fade to nothingness, who want to love an idea or a person so much it becomes fatal, who want to die young. Because those who question want to know what’s important and want to believe in why. They don’t want to live; they want to survive. To live while they die. To die while they live. They don’t want to die; they want to begin. So come. Question. And watch it all unfold before you.

Christina Qiu ’19, lives in Matthews Hall. Her column appears on alternate Tuesdays.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.