News

Cambridge Residents Slam Council Proposal to Delay Bike Lane Construction

News

‘Gender-Affirming Slay Fest’: Harvard College QSA Hosts Annual Queer Prom

News

‘Not Being Nerds’: Harvard Students Dance to Tinashe at Yardfest

News

Wrongful Death Trial Against CAMHS Employee Over 2015 Student Suicide To Begin Tuesday

News

Cornel West, Harvard Affiliates Call for University to Divest from ‘Israeli Apartheid’ at Rally

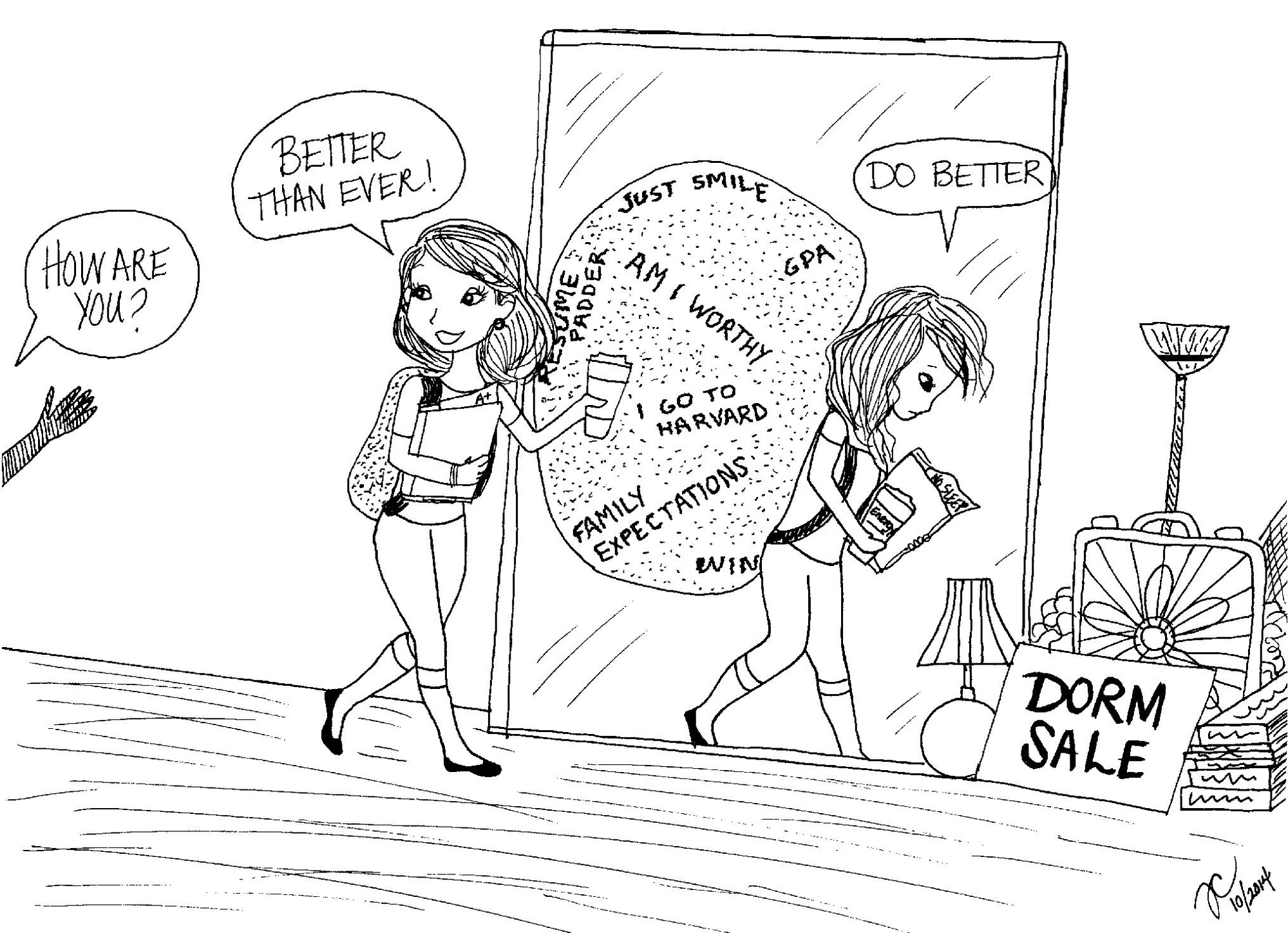

Lying to the Man in the Mirror

Self-affirmation and its pitfalls

I guess it’s kind of strange that I read articles on Buzzfeed that talk about “loving your own body.” In my defense, they do seem to be everywhere. And studying gets boring sometime. So why not read?

Though these articles are usually aimed at those outside my demographic, it is not hard to pick up on the ridiculously positive message. The topic covered in these articles reach farther than the concerns of stressed, bored college students. Individuals in our generation (fat, skinny, or anything in between) are obsessed with trying to establish their own sense of self-worth.

This issues does not deal only with body image. Almost everything about an individual is subject to a feeling of dissatisfaction and, ultimately, meaninglessness. The solution, at least according to Buzzfeed, boils down to looking in the mirror and learning to “love yourself.”

Our society runs with this solution. We seek affirmation of our own importance, whether consciously or not. As a matter of fact, this principle applies to the mass politics of our day. Some apparatchik stands up in front of a crowd and tells them that their problems and issues matter. And then, after the speech is done, said official sticks around to take photos with voters dying to update their Facebook profile.

So begins the cycle of self-affirmation.

When we don’t get that validation from other people–say, at a place where everyone is ridiculously talented in some way–the tendency, understandably, is to sulk. In order to have any kind of productive society, people have to believe that they can contribute something.

Of course, that is a pretty utilitarian view of how societies work. The issue of self-worth deals with people’s emotional and psychological states, not what role they would fulfill in an efficient utopian society. We are better off in a world where people are convinced that they can contribute something.

And yet, the end result oftentimes ends up being tragically ineffective.

The unspoken consequence of self-affirmation–of telling yourself that you are a decent human being– involves the search for your own singularity. In other words, you must be better than others at a certain thing. As a result, the idea of who feels better about themselves becomes a competition in and of itself.

Nobody likes to be a complement. We like to take control of our own destinies and shape the direction in which our lives go. That is why the idea of self-worth is itself so appealing. Finding our individual value apart from the accomplishments of others is a noble undertaking. It is a way to ensure that we find our place and role in the world.

But imagine a world in which everyone is always trying to convince themselves that they’re worth something. There would a lot of existential angst–but that is a topic best left to columnists, not the general populace.

This dialogue can just as easily swing in the opposite directions with reminders of how not awesome we are. Sometimes, our generation as a whole needs to hear that nobody cares what cool places they’ve been to or the awesome things they’ve done. But there are countless others who are keenly aware of the fact that their lives are not that awesome. Chiding, condescending remarks don’t do much for them.

But the danger is that we stay stuck in one place. Like the voters receiving the glad-handing politician’s compliments, we end up getting the things that make us feel better about ourselves. This is part of the reason why people seem concerned with making others think that they are confident in their own skin. We would rather lie to ourselves than acknowledge that we have real areas where we can improve. The fact that we are able to notice our faults is a blessing, not an unwanted consequence of self-awareness.

Life is not about admiring who we are now. Some people would still argue that the best solution is, in today’s vernacular, to “love yourself.” But self-affirmation requires a love that is honest. It acknowledges flaws and mistakes, pointing us to places where we could do better. It seeks improvement, not ego-pruning.

I look in the mirror and see that I don’t like the shape of my body. It’s not a call to love who I am. It’s a call to real improvement, not psychological self-deceit.

Al Fernández ’17 lives in Eliot House. His column appears on alternate Fridays.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.