News

Cambridge Residents Slam Council Proposal to Delay Bike Lane Construction

News

‘Gender-Affirming Slay Fest’: Harvard College QSA Hosts Annual Queer Prom

News

‘Not Being Nerds’: Harvard Students Dance to Tinashe at Yardfest

News

Wrongful Death Trial Against CAMHS Employee Over 2015 Student Suicide To Begin Tuesday

News

Cornel West, Harvard Affiliates Call for University to Divest from ‘Israeli Apartheid’ at Rally

Revamping Congressional Redistricting

Congressional Democrats are on the warpath. In November 2004, they saw five Democratic house seats in Texas succumb to Republican challenges as a result of mid-decade redistricting. With the Georgia Republican Party planning to repeat the Texas gambit, Democrats are anxious to return fire with mid-decade redistricting efforts in Illinois, Louisiana, and New Mexico, according to a recent report by the Capitol Hill newspaper Roll Call. While we understand the Democrats’ frustration, the long-term answer to efforts such as those that occurred in Texas is not retaliation, but reform.

In seeking to follow the Constitution’s vague declaration that “Representatives shall be apportioned among the several States…according to their numbers,” states have traditionally redrawn congressional district lines every decade to account for population shifts evident in the Federal Census. The only requirements imposed by the courts are that each district must be contiguous and composed of approximately the same number of residents. The vast majority of state legislatures have given themselves the authority to preside over this process.

Of course, most state representatives do not take on this cartographical responsibility out of altruism or a concern for fairness: from the very beginning, self-interested partisans have manufactured districts with bizarre shapes, splitting apart logical geographical communities in an effort to maximize a given party’s political advantage. “Gerrymandered” districts additionally serve to bolster the power of incumbents. When coupled with disparities in campaign contributions, cleverly crafted districts make the possibility of an upset by challengers (often consisting of women and minorities) incredibly difficult. The success of these plans is evident in the fact that incumbents are routinely re-elected at extraordinary rates. In last November’s Congressional elections, 98 percent of incumbents were reelected.

While gerrymandering has existed since the early days of the U.S., recent developments have exacerbated the problems inherent in any system which gives the power of redistricting over to politicians. In addition to the advantages of computer technology in crafting elaborate districts, the timetable for these battles has shifted. A recent unprecedented effort at mid-decade redistricting in Texas, orchestrated by House Majority Leader Tom DeLay (R-Texas), succeeded in picking up five Democratic seats this past November. While politically motivated redistricting schemes have long been de rigeur, the timing of DeLay’s actions have set a dangerous precedent. Assistant Professor of Law Heather K. Gerken explains, “The rules were, fight it out once a decade, but then let it lie for ten years. DeLay’s tactic was so shocking because it got rid of this old, informal agreement.” If the leaders of majority parties in other states follow as it appears that they will, the example set by Texas Republicans—attempting to maximize their political strength through perpetual legislative battles over redistricting—could lead to general democratic instability and greater cynicism on the part of the American people.

Either the judiciary or the states must stop one of America’s most undemocratic practices from spurring an electoral crisis. Since the Supreme Court instituted the “one man, one vote” concept in Baker v. Carr in 1962, it has played a pivotal role in regulating election law, sparking what many scholars have termed the “reapportionment revolution.” Unfortunately, the Court has been reluctant to intervene in cases involving partisan gerrymandering. Last year, in Vieth v. Jubelirer the Court ruled that it would not invalidate Pennsylvania’s highly partisan redistricting scheme, which sent twelve Republicans and only seven Democrats to the House in 2004 from a state that has not supported a Republican presidential nominee in nearly two decades. As the Washington Post lamented, the Supreme Court “examined a fundamental breakdown in American democracy and responded with a shrug.” If Vieth’s tenuous five-to-four majority remains in place, then the Court probably will not intervene to stop any partisan redistricting plans. That precedent, coupled with the potential repercussions of the Texas redistricting scheme, have laid the groundwork for a crisis in the democratic process. The next time a party wrests control of the executive and legislative branches in a large state, its leadership may imitate Delay’s tactics. Such a move would wreak havoc on the democratic process.

Without the Supreme Court’s intervention, the onus is now upon state governments to reform the redistricting system. Some have already taken steps to overhaul their redistricting processes. Independent commissions have drawn the lines in Iowa since the 1990 census and in Arizona since the 2000 census. California governor Arnold Schwarzenegger has made redistricting one of his top legislative priorities, and the Florida Democratic Party has also made plans to introduce redistricting efforts. While these recent efforts are laudable, many of them are still overtly political. California Republicans, such as Schwarzenegger, support redistricting in large part because the most recent alternative plan favors Democrats. Florida Democrats want redistricting reform to increase their share of representatives in the state’s congressional delegation. The movements in California and Florida have focused their plans on increasing electoral competition, itself a political end. Under their plans, redistricting would remain a political process.

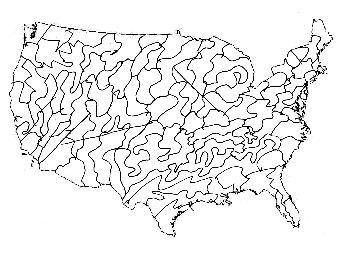

The focus of redistricting reform should not be a political one, such as competition or partisan gain. Rather, it should be on taking the politics out of redistricting and on drawing districts that are geographically and demographically consistent. The Redistricting Policy Group of the Institute of Politics has sought a non-partisan solution to the redistricting crisis. Comprised of more than twenty Harvard College students from a variety of political persuasions, we have formulated a blueprint for redistricting reform that we are introducing at the John F. Kennedy, Jr. Forum tonight at 6 p.m. Our plan would shift control of congressional redistricting into the hands of a nonpartisan commission independent from the state legislature. We layout several guidelines that commissioners should follow: every district should be as compact as possible, district lines should coincide as much as possible with municipal, neighborhood, and physical boundaries, as well as with state legislative district lines. States, of course, vary in their institutional make-up, and we do not expect our plan to be one-size-fits-all. We do, however, hope that states will incorporate the non-partisan spirit of our report into its plans.

For decades, partisan gerrymandering has gotten steadily worse, and citizens, confronted with this complicated process, have generally responded with confusion and indifference. However, as the situation degenerates into political chaos, and blatant inequities with the status quo become evident to all, we are confident that more and more Americans will join us in pressing for meaningful reform.

Paul B. Davis ’07 is a history concentrator in Kirkland House. Ari S. Ruben ’08 lives in Matthews Hall. Both are members of the Redistricting Policy Group at the Institute of Politics.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.