News

Cambridge Residents Slam Council Proposal to Delay Bike Lane Construction

News

‘Gender-Affirming Slay Fest’: Harvard College QSA Hosts Annual Queer Prom

News

‘Not Being Nerds’: Harvard Students Dance to Tinashe at Yardfest

News

Wrongful Death Trial Against CAMHS Employee Over 2015 Student Suicide To Begin Tuesday

News

Cornel West, Harvard Affiliates Call for University to Divest from ‘Israeli Apartheid’ at Rally

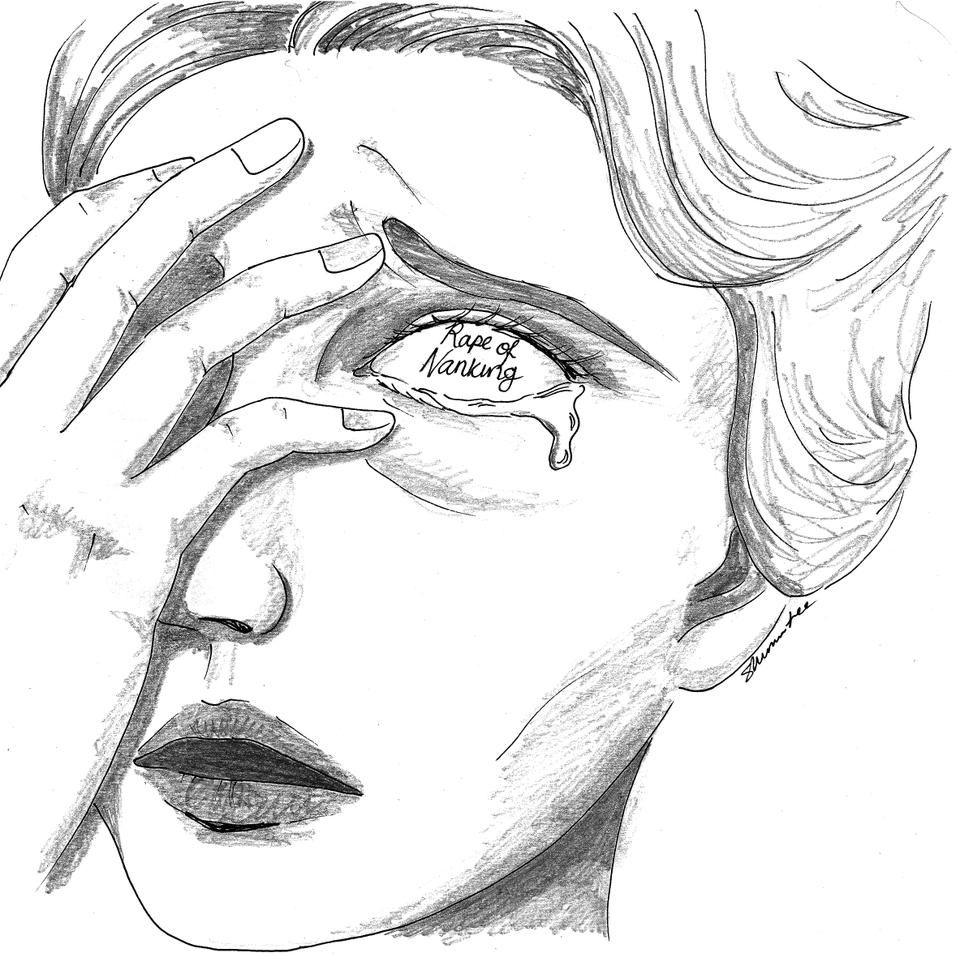

Despite Shallow Heroine, 'Nanjing Requiem' Moves

'Nanjing Requiem' by Ha Jin (Pantheon)

The opening paragraphs of Ha Jin’s latest novel, “Nanjing Requiem,” are as relentlessly brutal as the event they describe. With little fanfare Ban, a scrawny teenage messenger, recounts his experience as a Chinese captive of the Japanese Imperial Army, relating an onslaught of gruesome images: “Along the way every pond and every creek had dead bodies in it, humans and animals, and the water changed color. When we were thirsty, we had no choice but to drink the foul water.” Ban’s meager rice rations have a red tinge, leaving him with the taste of blood in his mouth for hours. At the end of Ban’s harrowing story, Jin’s narrator Anling merely adds, “I jotted down what he said.” Anling’s response may seem callous to contemporary readers, but Jin’s intent is not to create a historical account of the victims of the Nanjing massacre. “Nanjing Requiem” is instead an ode to an individual who fought against the atrocities, the American missionary Minnie Vautrin. Though Jin’s portrayal of Vautrin is less dynamic than one might expect from a National Book Award-winning novelist, he is nevertheless able to present a spare, compelling perspective on the calamitous events around her.

Vautrin—or Minnie, as she is called in the novel––was one of few foreigners who stayed in Nanjing during the Nanjing Massacre, a six-week-long period of genocide and mass rape at the hands of the Japanese Imperial Army, beginning in December 1937. Hundreds of thousands of Chinese civilians and disarmed Chinese soldiers were murdered, and it is estimated that 80,000 Chinese women were raped. Vautrin stayed as the dean of Jinling Women’s College, opening the campus to nearly 10,000 refugees. With little else but courage and a small American flag, Vautrin saved lives by confronting Japanese soldiers who entered the campus. Yet despite her efforts, the makeshift refugee camp was far from immune to the terrors of the massacre. Over the course of Jin’s novel, Japanese soldiers abduct civilian men and women from the camp and rape even occurs within its confines.

Jin’s stark prose is apt for these events; a more vivid lens would render the novel’s events even more unbearable. On more than one occasion, Minnie interrupts brutal rapes at the campus. “Startled,” Anling recounts, “the man pulled out his hand and rose to his feet, still smiling with his lips quivering. The woman, moaning in agony, closed her eyes and turned her head to the wall, a small birthmark below her right ear. Her body reminded me of a large piece of meat for cutting, except for the spasms that jolted her every two or three seconds.” The unrepentant soldier is able to leave the situation unscathed while his mutilated victim writhes on the floor. Minnie demands that this officer be punished for his actions and the superior officer’s reply is nearly as abhorrent as the rape itself. The officer grins, telling Minnie that the rapist is nicknamed “the Obstetrician.” Occasionally, though, Jin’s blunted language is less effective than in this harrowing passage. A technique that is necessary and powerful when describing atrocities does not export well to the dialogue. Because of this, the authenticity of the novel fluctuates, but overall this is a minor complaint and Jin’s style is mostly appropriate.

Minnie’s actions are filtered through the perspective of her fictional assistant, Anling, who narrates the novel with a stoic air. Her plainspoken observations are one of the few reasonable moments in an environment dominated by an unfathomable degree of violence. On one occasion, she notes that most of the Chinese recruits seem to be weak, illiterate teenagers from the countryside, “sent to the front as nothing but gun fodder.” Jin’s narrator with an “iron mouth and a tofu heart” is more than a convenient plot device and a recorder for Vautrin’s experiences. When Anling’s calm exterior finally breaks, the effect is startling, and her responses serve as a litmus test of the situation’s stress.

However, Jin’s portrayal of Vautrin is more reverential than multifaceted. Minnie works tirelessly to care for the refugees, who christen her “The Goddess of Mercy.” Though Anling is an effective narrator in many respects, Jin’s portrayal of Vautrin reveals little depth or introspection. Obscured by a veneer of moral certainty, Vautrin is portrayed just like her moniker suggests: as a goddess and a paragon of morality. Vautrin killed herself after surviving one of the worst genocides in history, haunted by her experiences and her guilt over not saving more lives. Yet Jin’s exploration of her trauma is a peripheral one, leaving her profoundly uncompelling as a character.

Despite the shortcomings of characterization, Jin engages with the political context of the massacre tastefully, imbuing the novel with subtle nods to the massacre’s legacy. An article casting the Japanese soldiers in a heroic light appalls the characters and alludes to decades of Japanese revisionist history of the event—some historians even claim the massacre did not occur. Jin does not explain the events, but instead allows the characters to discern their meaning for themselves, and when they do so, they are devastated by the injustice. For example, Jin does not simply state that General Chiang Kai-Shek is leaving Nanjing to its fate. Instead, Angling learns this when she sees Chiang’s wife’s donations arrive at the refugee camp: a piano and Victrola. Anling then realizes that he believes the Japanese invasion of Nanjing is unstoppable. The absurdity of the Chiangs’ frivolous donation is one of many ingredients that contributes to the novel’s sense of futility and hopelessness.

Indeed, the most significant contribution of “Nanjing Requiem” to the wealth of literature on the massacre is Jin’s elegant rendering of the event’s violence. Jin conveys how the events are not only fearful but also absurd, adding an extra layer of meaning to the characters’ suffering. Even though we are rarely granted access to Minnie’s internal thoughts, the immersive depiction of Nanjing’s horrors ensures that we can understand the cause of her psychological disintegration after the massacre. Despite the weaknesses in her portrayal, Minnie’s ability to function courageously in the Nanjing of Jin’s making gives this requiem its desired resonance.

—Staff writer Hayley C. Cuccinello can be reached at hcuccinello@college.harvard.edu.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.