News

Cambridge Residents Slam Council Proposal to Delay Bike Lane Construction

News

‘Gender-Affirming Slay Fest’: Harvard College QSA Hosts Annual Queer Prom

News

‘Not Being Nerds’: Harvard Students Dance to Tinashe at Yardfest

News

Wrongful Death Trial Against CAMHS Employee Over 2015 Student Suicide To Begin Tuesday

News

Cornel West, Harvard Affiliates Call for University to Divest from ‘Israeli Apartheid’ at Rally

Divinity and Desperation at the Forefront of Kunzru’s Latest

"Gods Without Men" by Hari Kunzru (Knopf)

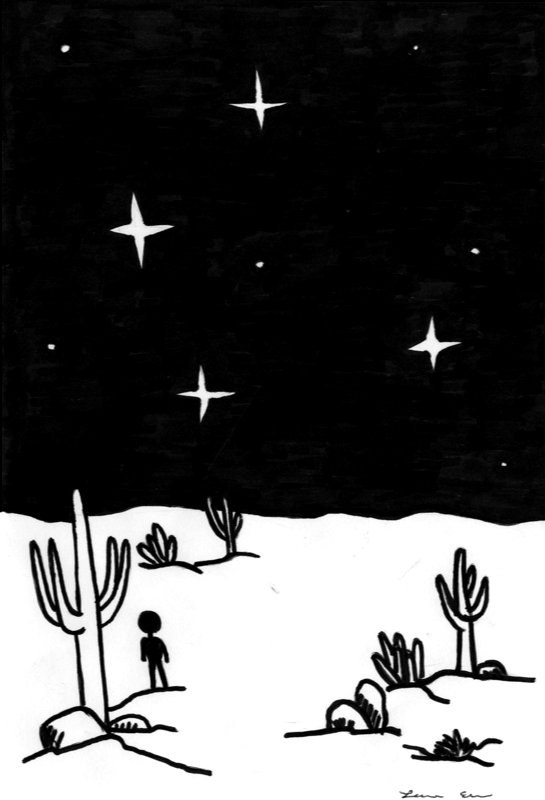

Did you know that a god-like coyote created methamphetamines? According to author Hari Kunzru’s novel “Gods Without Men,” at least, he did. The Coyote God of mischief and schadenfreude mixes up chemicals, blows his face off—don’t worry, he is resurrected three times by various animal friends—and is left with 100 grams of pure crystal whose use explains the delightfully psychotic nature of Kunzru’s latest work. The novel grapples with different portrayals of gods in the lives of characters as diverse as a mystically “cured” autistic boy, a jealous man with a Sikh background, and a desperate woman with a Jewish heritage. Through devotion to careful diction and seamless fluctuation between a dozen different writing voices, Kunzru’s novel shines as brightly as the setting’s desert sun.

The action follows Jaz and Lisa Matharu, two well-educated professionals who are vacationing in the Mojave Desert with their severely autistic four-year-old son Raj. Kunzru beautifully captures the anguish of a mother who is determined to cure her son: “Soon she’d abandoned her old reading altogether, the literary novels with bleak endings, the books about environmentalism or human rights. Those things felt like luxuries now, baubles for people who had no battles of their own.” Kunzru’s description of this frustration against a condition that both tears apart families and also invites endless public scorn proves incredibly realistic. One poignant portrayal of this derision is the Matharu family’s forced exodus from a series of hotels due to Raj’s loud tantrums. When Raj wanders off into the desert and returns with the capacity to learn, Lisa’s rediscovery of her Jewish roots comes as a highly satisfying moment—her prayers have been answered, and the reader has born witness to the emotional turmoil behind her decision.

Kunzru also focuses on an eclectic list of supporting characters who all have their own ties to spirituality and gods. Early in the story, Kunzru introduces a cult leader named The Guide who allegedly makes contact with aliens by digging a bunker in the middle of the Mojave and painting “Welcome” on the roof. Deluded by guilt from his experience fighting in World War II and the advent of nuclear weapons, The Guide preaches a message of world peace to followers who engage in bizarre, chanting cult rituals. The switch in narrative voice to this character’s calm demeanor serves as excellent juxtaposition to the Matharus, whose prayers for a miracle are so interrupted with real-life stress that they could never hope to achieve the The Guide’s calm fatalist perspective.

The most compelling voice, however, is not the relatively mainstream Matharus or wacky The Guide, but rather that of disillusioned rock musician Nicky. He runs away to the desert with peyote and a gold-plated gun to escape from Los Angeles squalor. Every character in the novel interacts mystically with the desert, but Kunzru’s portrayal of an artist who can hardly string together everyday thoughts yet exhibits unexpected compassion is especially admirable. More than anyone else, Nicky truly understands Raj. Like all the other characters, he also has a pseudo-religious experience in the desert—”The cacti raised their arms up to heaven. He wondered about joining them, praying for forgiveness. He felt sick. Would [his girlfriend] forgive him? What about all the others? He got down on his knees. Sorry, he whispered. I didn’t mean anything by it.”

Thus, Kunzru’s descriptions of religion run an impressive gamut from the commonplace to the unexpected. He describes parents praying for a cure for their child and using religion as a barrier against strangers, a rock musician using substances and women to distract himself from suicide, a guilty soldier atoning through religion, and the impious Coyote—who serves as the only representation of a real god in the novel. Five more perspectives supplement the novel with further ideas about the interactions between religion, spirituality, and this desert.

However, instead of falling into an established pattern of magical realism, the strongest parts of the novel are the moments rooted in human nature; indeed, a more fitting title might have been “Men Without Gods.” For all of the divine encounters in the Mojave Desert, it is the personal travails of each of the characters that make for compelling reading. Jaz and Lisa’s struggle against the media attack following their son’s disappearance is more powerful than Raj’s transformation in the last quarter of the book; likewise, the ability of The Guide to gain such a cult following based on a ridiculous premise is more intriguing than his original alien encounters. The supernatural ultimately retreats before the endless fascinating aspects of human suffering and triumph.

“Gods Without Men” is carefully written, constructed, and packaged; the prose is beautiful, every character is fully developed, and the desert itself will prove memorable even as the sands of time blow grittily across the novel’s pages.

—Staff writer Christine A. Hurd can be reached at churd@college.harvard.edu.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.