News

Pro-Palestine Encampment Represents First Major Test for Harvard President Alan Garber

News

Israeli PM Benjamin Netanyahu Condemns Antisemitism at U.S. Colleges Amid Encampment at Harvard

News

‘A Joke’: Nikole Hannah-Jones Says Harvard Should Spend More on Legacy of Slavery Initiative

News

Massachusetts ACLU Demands Harvard Reinstate PSC in Letter

News

LIVE UPDATES: Pro-Palestine Protesters Begin Encampment in Harvard Yard

‘Flatscreen’ a Dark yet Humorous Portrait of Wasted Youth

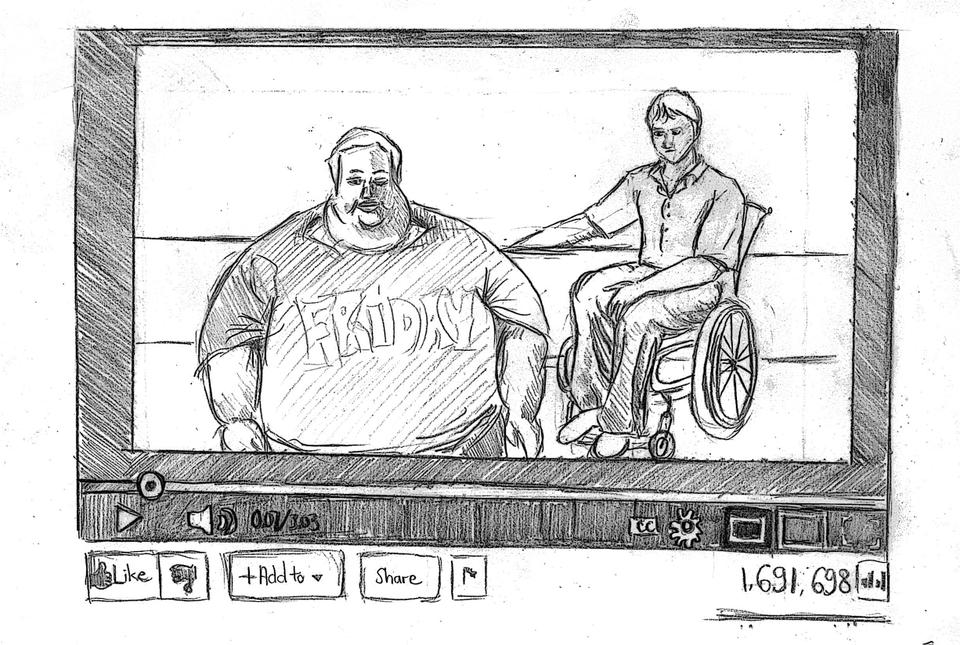

'Flatscreen' by Adam Wilson (Harper Perennial)

The much-maligned Millennial generation has been accused of many things: laziness, ingratitude, and gluttony, to name a few. If these terms apply to any 20-something, they apply to Eli Schwartz, the perfectly depressing embodiment of modern America. He is overweight and jobless, lives in a basement, and uses copious amounts of drugs. As the product of divorced parents who spoiled him out of guilt, Eli has quite a repugnant personality. Yet in his poignant debut novel “Flatscreen,” author Adam Wilson introduces a pensive and sensitive side to a character that, based on first impressions alone, is easy to abhor. The book is an effective homage to a generation of Facebook-obsessed, thin-skinned internet nomads. This timely topic creates an allure to Wilson’s writing, and college readers may sense in the realist work a pang of self-recognition. Yet instead of veering into pretentious judgement of an emerging generation, he instead grounds his novel in sharp wit and satirical slant—an impressive and unexpected amalgamation of J.D. Salinger’s commentary on youth and South Park’s relentlessly crass yet astute observations.

Eli’s existence, which is usually spent in a tattered L.L. Bean robe, consists of nothing more than television, food, drugs, the internet, and daydreaming about futures he could never attain and girls he could never sleep with. He is dependent almost to the point of parody: he lives off the guilt-sodden checks from his unfaithful father, takes advantage of his helpless mother, and burdens his older brother. At the beginning of the novel, Eli’s mother’s house is sold to a paraplegic, drug-addled, lonely, and sex-addicted retired TV star named Seymour Kahn. His life runs parallel to Eli’s sense of purposelessness; the pair soon become close, and Kahn assumes a position of a father figure, albeit one with unlimited access to Oxycontin and prostitutes.

Eli is a typical burnout—high in synagogue, high in high school, high at Thanksgiving—and, having grown up comfortably middle-class, he cannot defend his drug habits with an excuse of life on the streets. His sheltered and spoiled life makes him the farthest thing from a pitiable character, at least judged from the advantageous circumstances in which he was born. However, through his narration of the story, the reader gains insight to his mind—and that mind is surprisingly relatable. After a drastic disappointment, he thinks, “I’d seen this movie. Obvious ending: outright betrayal, lesson learned, life is heartbreak, people who mean well still fuck you over, everyone’s sad, greedy, looking out for number one, no consideration for the fragile fat boy whose displayed cynicism only masks a deeper hope that everyone’s okay, will ultimately end up all right, that love exists, that happiness may not be stable but at least comes in bursts, that everything worthwhile wasn’t just a self-created illusion.” His self-awareness is compelling, and his ability to honestly voice his often meaningful and depressingly realistic opinions is a boon to the story.

As Eli drifts through life on a constant high, he replaces his familial and friendly relationships with the soft sigh of a hit of a joint, the swift excitement of a line of coke, and the numbing embrace of various pills, crack, and even a stint with Viagra. His dependence on these drugs for variety in his life catalyzes a series of events that lead to his being cut off from his father, becoming a YouTube sensation, sleeping with a married woman and then getting beat up for it, and getting shot. These moments of mindlessness, however, sometimes come off as trite moralizing on the part of the author, which distracts from the selfish and drifting nature of the protagonist’s worldview.

Unexpectedly, and to the book’s credit, there is ultimately no predictable eye-opening realization by Eli that his life would be better without an endless barrage of drugs. Wilson delves deeper into the psychological and societal underpinnings of Eli’s drug abuse and complete self-centeredness. He explores the result of growing up with unloving parents (“My existence underscored her failure,” says Eli of his mother), living with no perceptible drive for a successful future, and never needing to work for anything.

Complete with lists, short chapters, inconclusive tangents, citations of films, screenplay snippets, and subject-less verbs, the book is a literary reflection of society’s short attention span. “Ways In Which I am Like a Rapper,” Eli posits. “Absent father, bullet hole, verbal dexterity, limited education, love of butts.” Wilson writes for a modern audience with an insatiable appetite for constant fast news, and he employs various writing tools to help the reader remain interested. He masterfully couples deep musings with forceful droll to create the perfect oxymoron: a likable asshole. His writing—like the rapper list—is fresh and witty and drips with both pop culture references and philosophical morsels that create a reading experience that is enjoyable beyond a superficial level. The story seems too generally dark, however, for its marketed label of comedy; the lives of the various characters are reminiscent of the lives of countless suburban families depressingly hiding behind material possessions.

Wilson concludes the novel adroitly, given its focus on a genuinely mediocre character for whom a traditional happy ending seems implausible. He concocts 19 “Possible Endings,” from which the readers can claim their own desired conclusion. At first glance, this is perhaps a cowardly way to end a story, yet Wilson pulls it off and gives at least a glimmer of hope in Eli’s future.

This arresting and raunchy novel begs attention. Wilson’s practically flawless ability to meld a philosophizing monologue with a scene of someone drugged out on a high school football field with an enormous erection creates a balanced novel for both those who want to be entertained and those who want to be inspired.

—Staff writer Charlotte M. Kreger can be reached at charlottekreger@college.harvard.edu.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.