Behind the Scenes of HUCTW's Negotiations

Though this year’s negotiations were long, sometimes riddled with frustrations and other times with rewarding compromises, HUCTW members said this process was decidedly less antagonistic than previous negotiations.

When Harvard and its largest employee union last came together to negotiate a contract, the process extended eight months past the expiration date of their contract. Protests by student groups and union workers highlighted the union members’ exasperation and frustration with the University.

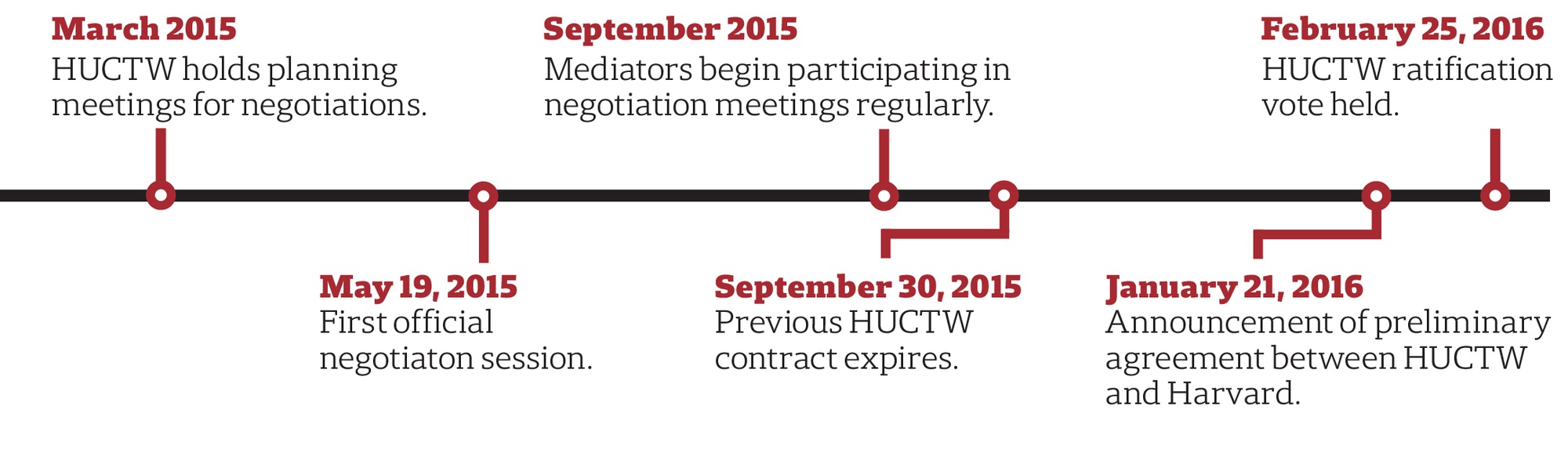

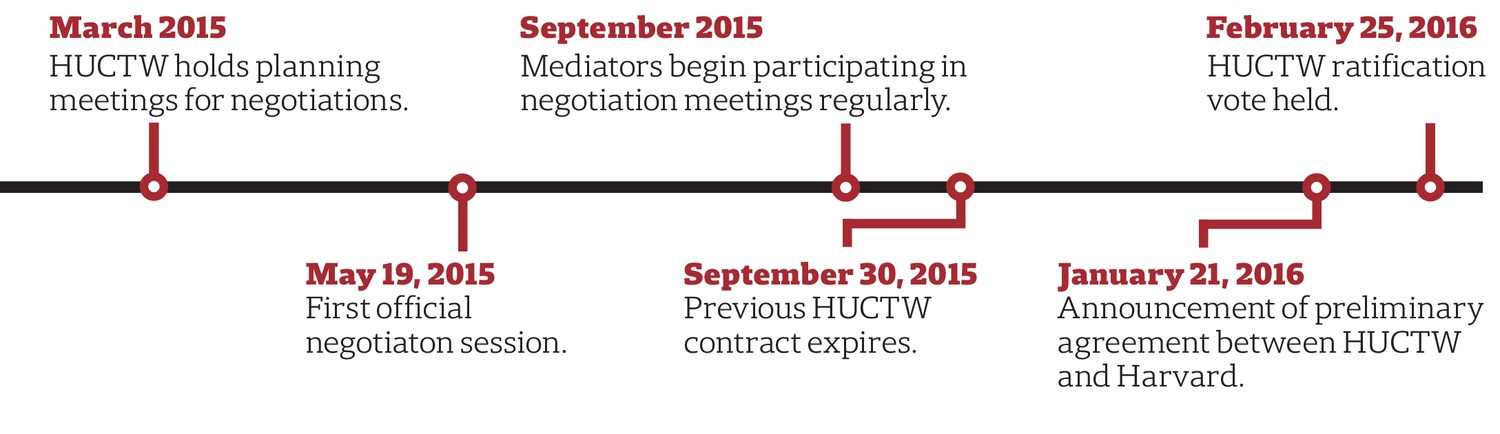

This time, the process was much more amicable. Indeed, the negotiations were lengthy and, at times, strained, but members from both sides of the table agreed they ended up with a contract that was satisfactory for both sides. The finalized contract came in late January, and the Harvard Union of Clerical and Technical Workers officially ratified it last week.

In order to foster a cooperative relationship with Harvard, it was important to frame the negotiation’s outcome in a “way that doesn’t make it look like somebody’s winning and somebody’s losing because that’s never going to be productive,” Donene Williams, a member of the negotiation team for HUCTW, said.

Yet, by the time both sides arrived upon a mutually acceptable agreement, four months had passed since the expiration of the previous 2013 contract. More than 95 percent of HUCTW members who cast their ballots voted in favor of the contract’s adoption last Thursday.

Though this year’s conversation was long, sometimes riddled with frustrations and other times with rewarding compromises, HUCTW members said this process was decidedly less antagonistic than previous negotiations.

The working relationship between HUCTW and Harvard has improved substantially and dialogue between the two parties has become more cooperative—enough so that HUCTW members are optimistic at the outcome of future negotiations.

A PROLONGED PROCESS

The year of negotiations was marked by debate over wage increases and health benefits—the latter becoming so contentious that Harvard and HUCTW appointed outside mediators to facilitate discussions.

Both sides formally met more than 40 times over the course of the year, according to a Harvard press release. Carrie Barbash, a HUCTW union organizer, said the meetings typically lasted a minimum of two hours each, and took place twice a week during the spring and the fall in rooms at 124 Mt. Auburn St.

Amanda H. Wininger, a union member who works in Widener Library, said she had to allot “four hours a week of standing meetings in [her] calendar for months and months.”

Individuals from both sides sat across from each other at a table to negotiate, and they had “secondary rooms set aside where, if we needed to caucus—talk to our teams—we could,” Barbash said.

At times, the conversations became tense, and the smaller rooms were helpful when the negotiators needed to regroup.

“If we were frustrated with one another, sometimes it made sense to sort of separate and have the mediators sort of, well, mediating between us,” Barbash said. “And then we can react to things without them having to see it, because those reactions can sometimes upset people. Plus, your initial reaction isn't always what you come around to.”

Roughly 18 to 20 HUCTW members were part of the union’s negotiating team, and each individual had a specialized role. For example, Wininger focused on wage increases, while Williams and Susan M. Kinsella focused on health care.

Thanks in large part to a recent controversy over non-union employees’ health benefits, debate over health care often eclipsed other topics of discussion. Several HUCTW members said they were concerned about potentially receiving a similar package to what Harvard offered non-union employees in 2015. In 2014, non-union employees—many of whom were faculty members—primarily criticized the plan for its deductibles and copayments.

Harvard and HUCTW began by discussing each party’s general interests and specifying contract details as their conversations evolved. Harvard wanted a healthcare plan they could give to the majority of their employees; HUCTW sought one without the deductibles included in Harvard’s non-union package. The result: a prolonged process.

“It wasn’t just a simple conversation of the University saying ‘Here, we’d like to take this’ and us saying ‘no thanks,’ Williams said. “It was a lot more nuanced than that. There was a lot of discussion about why the University believed it would be a great idea for everyone to be on the same plan, and we didn’t disagree with that—we just didn’t believe that it was the right plan.”

Because of disagreement over health care, negotiations stagnated. As the expiration date of the previous contract from 2013 loomed ever closer, both sides called in mediators from Harvard and MIT to resolve debates over procedural items and expedite the negotiations process, Bill Jaeger, the Executive Director of HUCTW said.

The departure of Harvard's director of labor relations, Bill Murphy, in the middle of negotiations complicated the negotiations, Williams said.

Preparation for union negotiations itself was an extensive process. Both HUCTW and Harvard sought the expertise of consultants in health care and living standards prior to formal negotiations, according to Jaeger and Katie N. Lapp, Harvard’s executive vice president. Harvard initially focused on data collection, “including national and regional health-care and labor costs and trends,” Lapp wrote in an emailed statement.

Additionally, Barbash said, union representatives met individually before negotiations officially began in order to plan their discussion strategies.

HUCTW leaders sent a survey to union members in May and June 2015 to better understand their health care and wage concerns. In a report of the survey’s findings, individuals who led the negotiations wrote that they “have been using the stories and statistics from the survey to shape and strengthen” their discussions with Harvard.

As negotiations progressed, conversations about specific policies became more pointed, Jaeger said.

“At some point, probably in the fall, we moved past the sort of carefully designed and planned early phase of the conversations into a period where the disagreements were sharper, and the ideas being put forth by the two sides were more specific,” Jaeger said.

A HIGH STAKES GAME

Both stakeholders had to take into consideration the various constituencies they represented when negotiating. Harvard negotiates with nine unions and more than 6,000 unionized employees, while HUCTW must juggle the individual interests of each of its 4,600 members.

For Harvard, negotiations can become especially complex because the University cannot disproportionately allocate more financial resources for one union’s benefits package than for others.

In the negotiations, HUCTW members wanted to ensure that the deductibles included in Harvard’s recent non-union health benefits package—which union member Danielle R. Boudrow described as the “most dangerous part” of the plan—were not included in their new contract. Ultimately, Harvard offered HUCTW a package absent of any deductibles with a new premium contribution tier for employees whose salaries fall below $55,000, and featuring moderately increased copayments. Union members largely praised the contract.

Lapp wrote that Harvard tried to consider the increases in health care and living costs while also providing “strong wage and benefits packages to all employees in ways that also support our fundamental mission of research, teaching and learning.”

Though union members said they were at times frustrated with the length of the whole process, they said they would rather have a satisfying contract than an incomplete contract that was hastily agreed upon.

“It's more important to get the best possible agreement rather than the fastest agreement,” Boudrow said.

Under the new contract, a typical HUCTW employee will receive a 3.4 percent annual pay increase—an element similar to the previous contract with Harvard. Pay increases are scheduled for Oct. 2016 and 2017, and union members will receive retroactive pay increases for 2015.

Sarah E. Hillman, a HUCTW member and employee at the Harvard Medical School, said the contract’s wage increases were especially important because of the rising costs of living in Boston.

“I need a wage that can keep up with what it costs me to live in this area,” Hillman said.

Overall, HUCTW members said the negotiation process was positive. Williams said she believes the increased collaboration the parties saw this year will aid future negotiations.

“It’s a relationship, so what we do together in the next two and half years, that’s really going to be what helps us have a smooth negotiation process next time around,” Williams said.

When asked if there was anything that could be improved about the negotiation process, Williams laughed: “We could just agree on things sooner.”

“We were so far apart at the end of September, that it wouldn’t have been worth it to agree then just to meet the deadline,” Williams added.

Though negotiations extended past the deadline, there are still details to be worked out, including stronger language for guiding discussions about flexibility with employers and provisions addressing the union members’ parking and transportation concerns.

“We have a little bit of unfinished business, but we don’t usually, when we have unfinished business, wait three years to talk about it,” Wininger said. “We keep the conversation going.”

—Staff writer Brandon J. Dixon can be reached atbrandon.dixon@thecrimson.com. Follow him on Twitter @BrandonJoDixon.