News

Pro-Palestine Encampment Represents First Major Test for Harvard President Alan Garber

News

Israeli PM Benjamin Netanyahu Condemns Antisemitism at U.S. Colleges Amid Encampment at Harvard

News

‘A Joke’: Nikole Hannah-Jones Says Harvard Should Spend More on Legacy of Slavery Initiative

News

Massachusetts ACLU Demands Harvard Reinstate PSC in Letter

News

LIVE UPDATES: Pro-Palestine Protesters Begin Encampment in Harvard Yard

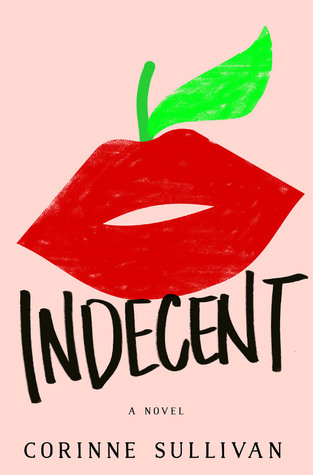

‘Indecent’ Botches its Feminist Love Story

1.5 Stars

“Heterosexual romance has been represented as the great female adventure,” Adrienne Rich writes in “Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence.” There’s always been a dearth of female characters whose narrative revolves around something other than romance, and in the wake of the #MeToo era, that type of story carries more value than ever. Unfortunately, “Indecent,” Corinne Sullivan’s debut novel, is not that story. When Imogene Abney secures a teaching position at the Vandenberg School for Boys, an elite boarding school, she thinks her lifelong obsession with boarding school culture has finally been gratified. But when she starts an affair with a student, Adam “Kip” Kipling, she puts her entire career in jeopardy, in a world that “shatters her sense of victimhood and blame,” according to the back cover blurb.

“Indecent” falsely advertises itself as a book that examines the sexual politics of teacher-student relationships in a critical and innovative way. What Sullivan delivers instead is a variation of a clichéd theme, narrated by an obsessed 22-year-old woman with the sexual experience and emotional complexity of an immature teenager. What’s being “shattered” is less a stereotype about female victimhood, and more Imogene’s own sense of autonomy. In a literary landscape that demands multifaceted and self-determined female characters more than ever, “Indecent” does not undermine the patriarchal hegemony—rather, it does everything in its power to uphold it.

“Indecent” hinges on many of the same impulses as another debut novel, Emma Cline’s stunning 2016 book, “The Girls,” which is about a teenage girl who joins a Manson-like cult. But while Cline’s sharply lyrical prose delves into the nuances of female adolescence, Sullivan’s borrows the voice of a young adult novel, and then proceeds to sap the voice of its vivacity. Like in “The Girls,” Sullivan’s plot presents the opportunity to draw out the systemic factors at work to hold accountable the society that socializes women to scrutinize their flaws, undermine their own ambition, and defer to their male counterparts. Instead, Sullivan provides a character sketch of an infatuated archetype, a woman so caught up nursing her own self-destructive impulses that she becomes uninteresting. “I wanted him to see different sides of me, to wonder what else I could be,” Imogene thinks. Sullivan spends so much of the novel elucidating Imogene’s self-sabotage that the reader begins to wonder whether those other sides exist. Indeed, Imogene spends a great deal of the novel crying: She weeps in the stairwells of Adam’s dorm, and sobs outside until someone finds her, and lies in bed for days at a time, wallowing. “The only way to indulge fully in my misery was to continue to believe Adam Kipling was the best thing that had ever happened to me,” she reflects. “And so I did, and I thought of him and dreamed of him and alternatively rubbed myself between my legs and sobbed until snot dripped down my chin.”

What’s even more tiresome than Imogene’s melodrama is the fictive world that seems inclined to forgive her, even when she shows up to class with a hangover after a wild night in the city, or only realizes that she’s forgotten to write the midterms on the day of the exam. This is a world in which many men—from an oft-referenced college fling to her superior, who is 10 years her elder—desire Imogene. Yet confusingly, she still pines for a barely-legal 17-year-old, whose attention often strays to other girls.

Imogene’s acute unpleasantness would be less obvious if her world wasn’t populated with characters who are infinitely more capable and more interesting than her—but it is. There’s Chapin, the unapologetic cool girl who becomes Imogene’s confidante (“Around Chapin Dunn, I was struck dumb, like a boy with a crush”). There’s Raj, Imogene’s attractive co-apprentice and Kip’s R.A. (“The idea of him having sexual experience made him unexpectedly alluring”). Even Joni, Imogene’s younger sister, contains the multifaceted depth that Imogene lacks (“I wished—as I had many times before—that I could be more like Joni. She never seemed afraid to take risks”). These characters, the objects of Imogene’s reverent fantasies, seem cursorily interesting—yet perhaps because of those fantasies, they quickly fall prey to the same one-dimensionality with which Sullivan treats her protagonist.

It might be possible to set aside these narrative flaws—perhaps chalk them up to an unreliable narrator. After all, there’s space in the world of books for genre novels that compensate for merely passable prose with a buzzy soap opera plot and a cast of attractive characters. But the sex in “Indecent” isn’t remotely alluring. It’s not just bad sex, but bad sex that Imogene imagines to be great sex, which is its own transgression. “Use your magical mouth to make me magically hard,” Kip says in one scene—the same scene in which he flicks his flaccid penis, “a useless pendulum,” and says “Uh-oh, SpaghettiOs.” Imogene finds Kip’s sexual attraction to her armpits endearing: “You know you’re into a girl if you’re into the smell of her pits,” he says. Later: “The way he pretended my nipples were buttons and would poke them with his finger and go, ‘Boop-boop!’” There isn’t enough legitimate literature about female desire, so it’s a shame that Sullivan squanders an opportunity to treat Imogene’s as anything more than a caricature of itself.

By the end of the novel, even Imogene seems exhausted from crying, from complaining, from having to contend with her own self-pitying storyline. “I feel even more pathetic,” she concludes. “I am a problem too unpleasant to contend with.” At least she gets that right.

—Staff writer Caroline A. Tsai can be reached at caroline.tsai@thecrimson.com. Follow her on Twitter @carolinetsai3.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.