A Social Social Studies Thesis

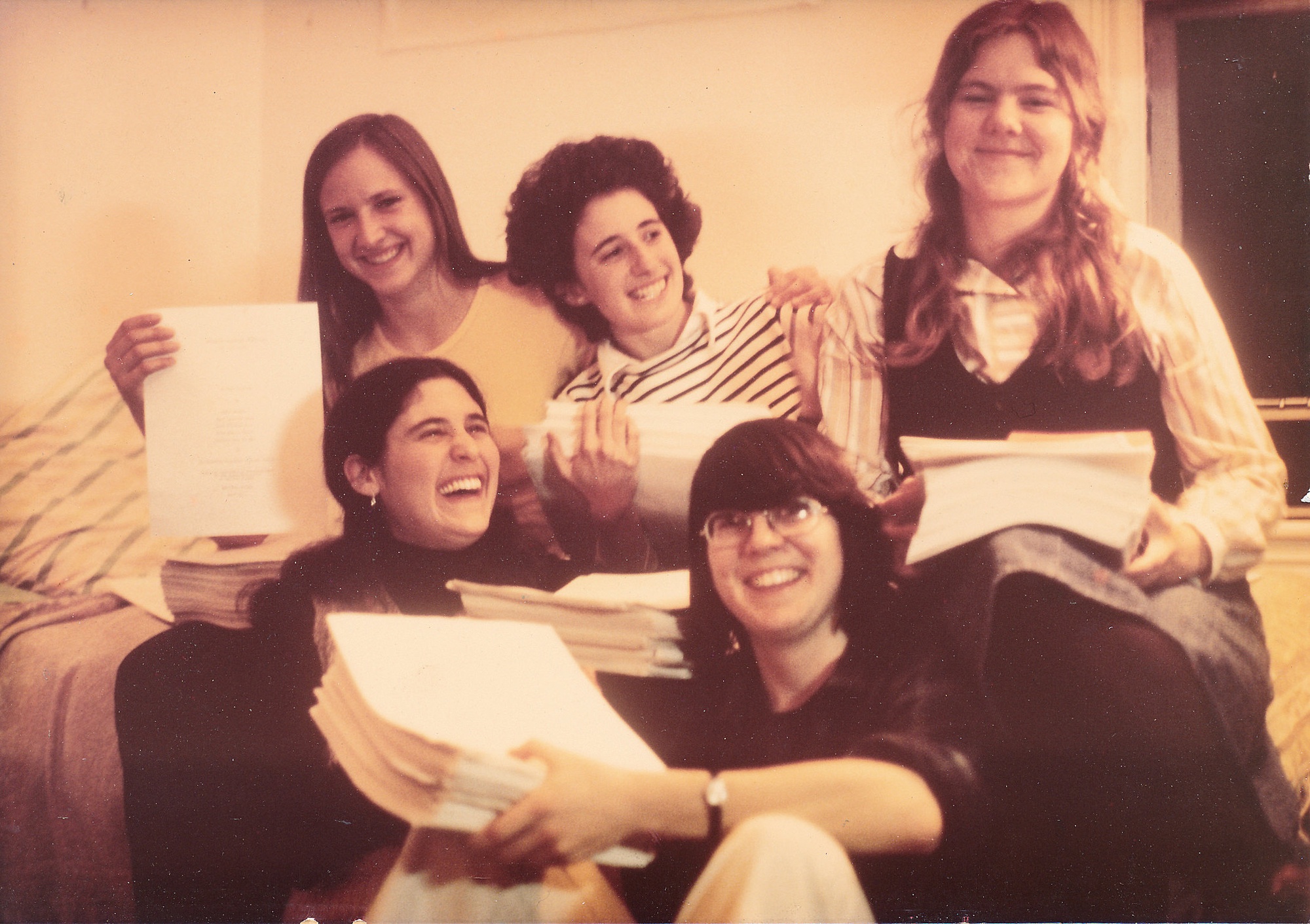

Bound in the weathered covers of three black volumes lie pages upon pages detailing one of Harvard’s hidden gems: A senior thesis with the unassuming title “Direct Action Organizing in the 1970s.” As the dust scatters from the typewritten pages, a story of five women, four advisors, and one vision comes to life.

The year is 1978, and five women gather outside the office of Social Studies department chair Michael Walzer. As they wait, shoes tapping, they discuss the most recent Phillips Brooks House Association meeting and debate strategies for empowering marginalized groups. They are here to write their thesis — together, not alone.

In several meetings like this one, these five women — Adair Dammann ’79, Susan C. Eaton ’79, Sarah E. Royce ’79, Karen R. Scharff ’79, and Stephanie A. Van Dyke ’78 — relentlessly advocated for themselves and their idea of writing the first —and to date, only — group Social Studies thesis in Harvard College history.

Walzer was convinced that they were ruining their academic careers by challenging the norm of thesis-writing based on individual thought and opinion. But the “Gang of Five,” as they came to be known, had no doubt that they made the right choice. After all, they were studying collective political action and saw no better way to do so than to work in a collaborative fashion. Together, the women persisted and finally received departmental approval.

All passionate about activism, the women focused their thesis on comparing the inner workings of the five community organizations where they had respectively interned the previous summer. Each woman then wrote a case study of her respective organization in the thesis after conducting interviews and analyzing data.

Despite their independent work, the process remained highly collaborative. “Everything started in one person’s typewriter and then went through everybody else’s,” says Dammann.

In taking on this project, the women challenged a widely-held definition of intellectual excellence — sitting alone in a library, independently working through one’s thoughts. Instead, the Gang of Five charted a unified path to a coherent and academically rigorous collective thesis.

Working in a group gave the Gang of Five a unique set of advantages. “We got so much more from what we got from talking with each other and from the ability to compare these five different organizations, and nobody writing alone could have had that set of data,” Scharff recalls.

“We intuitively believed we were smarter together than we were individually,” Dammann says. They knew they could achieve their highest level of academic excellence through working collaboratively.

Though still plagued by the perennial problems that all thesis writers experience, the Gang of Five had each other to lean on for support. When Dammann was crippled by writer’s block, her “friends circling up” around her and her sense of responsibility to the rest of the team helped her keep writing. After months of hard work, the Gang of Five turned in their final draft.

But, their story did not end there. The hours they had spent laboring over the one thesis had created an unbreakable bond. To this day, the Gang of Five gathers annually — always making sure that long walks and coffee are part of the agenda — and they regularly consult each other on every aspect of their lives, both professional and personal.

Recently, they realized that they could create a book club using Zoom, a video conferencing app. Chuckling, Dammann admits that the book club is just an excuse to catch up on their lives. “We get on our Zoom call for 90 minutes and we mainly talk about husbands and children and lives and careers, and we talk about the book for 10 minutes.”

In 2003, the Gang of Five faced the death of one of their own, Susan Eaton, who died after a battle with leukemia. To honor her memory and her service to Harvard and the greater community, they rallied classmates together and created the Susan C. Eaton Research Fund in Organizing, Leadership, and Social Change. “It seemed very logical to try and help people, to help Harvard students that were interested in working for social justice and social change,” Royce says. With the grant, they hope to enable students to pursue the work to which Eaton had dedicated her life.

Since graduating college, these five women have stuck together, only growing closer with the passage of time. “We do all major life events with the Gang of Five,” Dammann says. “We are with each other at every step.”

It has been 40 years since the Gang of Five turned in their thesis, and while so much has changed in their own lives and in the world around them, their core belief has not: They are, undoubtedly, better together.