News

Pro-Palestine Encampment Represents First Major Test for Harvard President Alan Garber

News

Israeli PM Benjamin Netanyahu Condemns Antisemitism at U.S. Colleges Amid Encampment at Harvard

News

‘A Joke’: Nikole Hannah-Jones Says Harvard Should Spend More on Legacy of Slavery Initiative

News

Massachusetts ACLU Demands Harvard Reinstate PSC in Letter

News

LIVE UPDATES: Pro-Palestine Protesters Begin Encampment in Harvard Yard

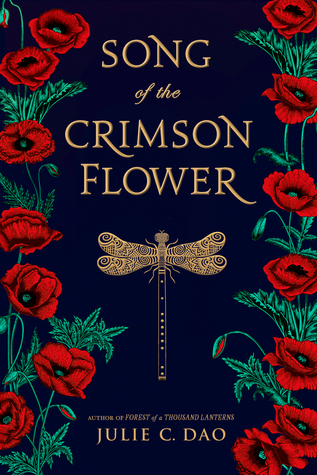

‘Song of the Crimson Flower’ Has a Romance that Fails to Bloom

2.5 Stars

Julie C. Dao’s “Song of the Crimson Flower” is a frothy, contrived concoction of pleasure reading and little more, offering far more shallow style than substance.

The “Song of the Crimson Flower” begins when young Lan, a wealthy member of the aristocracy, rejects the heartfelt proposal of Bao, a poor orphaned fisherman and physician’s assistant. After such a vicious, flinty dismissal, Bao flees his home and proximity to Lan and her family, and on his journey encounters a powerful river witch who seems to know him and casts a spell upon him. She reduces Bao’s essence to a ghostlike form inside his flute and decrees that the only way to reattain his true form is if a declaration of true love is made before the next full moon. She tells him to head south to the Gray City, the ominous birthplace of black spice, an opium-esque drug that pollutes Dao’s fictional society, to find his mother, who should surely love him. When Lan finds Bao’s flute and discovers the tale, to amend for her former cruelty, she accompanies him on the long trek, avowing to atone.

On the one hand, Dao’s fictional landscape is richly envisioned and lavishly textured; she describes the docks near Lan’s home with luxurious care: “Boats swept over the water, packed with nets of wriggling fish, buckets of jackfruit and spiny durian, and baskets of sweet, fragrant pastries wrapped in banana leaves… Men and women who had once played as children on the riverbank now rowed their goods to shore.” Likewise, Dao paints the tainted opulence of the Gray City’s drug trade with sinful decadence; Bao’s “skin crawled at the sight of the bronze-and-cypress furniture, the rare painted scrolls, and the jeweled trays… Death and black space had gilded each table and upholstered each chair with silk.”

But “Song of the Crimson Flower” is unfortunately a novel of surface-level embellishments that lacks a concrete foundation. Though Dao lavishes pages on expositional descriptions, she skims other vital points of narration. She does not, for example, describe a large battle that happens at the Gray City; rather, she diverts the reader’s attention to the escape of the protagonists from the palace. They emerge to find that the battle has more or less been miraculously won. Difficult, all-encompassing questions of plot progression do not develop and build over time. Instead, Dao places her protagonists against a backdrop of a war that conveniently falls into place around them.

In fact, Dao charts both plot and character development unevenly. She does not introduce the concept of a larger war until a third of the way through the novel, which is not terribly long to begin with. Likewise, she introduces a tangential romance to a group of side characters that appears hastily constructed. She simply does not devote enough attention to the romance and its development to make it credible — or, in a much more real sense, interesting for the reader. Dao has the unfortunate habit of introducing plot digressions far too late into the novel that she does not fully resolve. If she does reconcile them, she does so in the last few chapters, with hastily murmured declarations of love and miraculous battle techniques that the reader never actually sees.

One of the larger issues with the “Song of the Crimson Flower,” though, is its tendency toward the trite. It’s a novel of tropes, many of them world-wearied and worn. The motif at the center of the story, after all, is the unrequited love of a hapless peasant at the hands of a member of the nobility. Look at Wesley and Buttercup in William Goldman’s “The Princess Bride,” Anne and Captain Wentworth in Jane Austen’s “Persuasion,” or, even in a less literary sense, at Rose and Jack in the “Titanic.” The romance at the center of the “Song of the Crimson Flower” is wholly unexcitable; even its eventual outcome is predictable. The love story is so formularized, in fact, that it makes its progression almost boring for the reader. It ends with Lan’s tearful remission: “I’m sorry I wasted so much time. I’m sorry I never saw how wonderful you were.” Forget trite: It’s tired.

This all said, the “Song of the Crimson Flower” is not an irredeemable read. It’s pleasant, light fare, if one does not pay too much attention to a somewhat slapdash plot and unoriginal storyline, and Dao is a skilled worldbuilder. It’s a novel meant for quiet, unconcerned escapism.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.