News

Cambridge Residents Slam Council Proposal to Delay Bike Lane Construction

News

‘Gender-Affirming Slay Fest’: Harvard College QSA Hosts Annual Queer Prom

News

‘Not Being Nerds’: Harvard Students Dance to Tinashe at Yardfest

News

Wrongful Death Trial Against CAMHS Employee Over 2015 Student Suicide To Begin Tuesday

News

Cornel West, Harvard Affiliates Call for University to Divest from ‘Israeli Apartheid’ at Rally

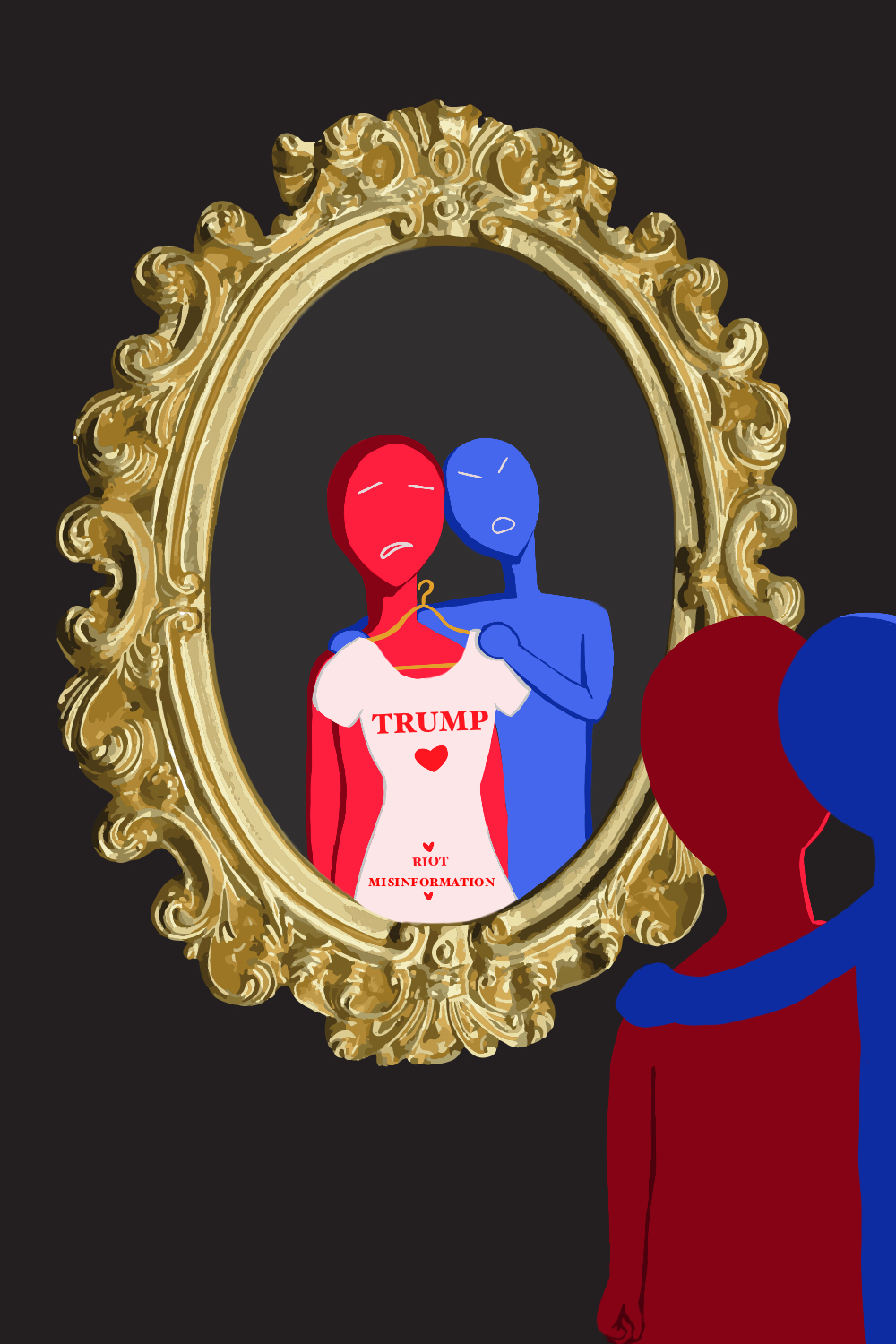

Who is to Blame for the Capitol Insurrection?

The insurrection at the Capitol on Jan. 6 has left Americans looking back on the collapse of a presidency and the collateral damage of divisive rhetoric. President Donald Trump’s unwillingness to concede the election and his inflammatory language enabled the loss of five lives and the desecration of a sacred symbol of democracy. As a conservative, I join in many Americans’ — including Democrats’ — outrage at this political violence and disrespect for constitutional processes.

As the dust settles, especially after a chaotic impeachment period, students are left thinking about who is responsible for the insurrection. Trump and the rioters themselves are the most immediately culpable, but how broadly does the blame spread? Is it all Trump voters? All Republicans? All non-liberals even?

At a place like Harvard, where many affiliates are connected to the Trump administration, it’s crucial that we grapple with this question. The problem, however, occurs when the finger pointing goes too far: Blame becomes ambiguous, reconciliation impossible.

Students, particularly on the far left, have started to interpret and assign the charge of enablement — the action of giving someone the authority or means to do something — far too liberally. The bigger problem, however, is that they have become obstinate against engaging with any perceived “enablers.” Should this continue, there will be a weaponization of “enablement” to shut down any opposing narratives.

The Crimson Editorial Board, of which I am a member, wrote in January that “every Trump supporter enabled the Capitol insurrection.” I believe it’s a little more complicated than that.

There needs to be more precision in the use of the word “enable” and a greater recognition of its multiple layers. In my opinion, anyone who lied about election fraud, especially those in places of power or with major media presence, enabled the insurrection. They gave credence to a false claim that had sparked unfounded outrage across the country since Nov. 3.

But does the same apply for Republicans and Trump supporters at large? Trump voters enabled the president’s effort to fan the flames of misinformation, which indirectly emboldened rioters. However, saying that voters directly enabled the rioters is a bit more tenuous.

There were 74 million Trump voters. 74 million. Those are our neighbors, our relatives, and our friends. Are we to write off each and every one of them an insurrection enabler, especially when many denounced the riots? Are they fully to blame for other people's decision to storm the Capitol?

The accusations of enablement are concerningly broad at Harvard, especially. And once someone is labeled as an enabler, they are written off as part of the “Trump problem” and ascribed all of its ugliest facets — all of their opinions are assumed to lack merit.

A striking example is the recent petition and open letters to develop new accountability measures that could block former Trump administration officials from teaching, speaking, or serving as fellows at the University. Some students who supported the petition even called for banning everyone who served in the administration.

But this too is an oversimplification. Miles Taylor, former chief of staff in the Department of Homeland Security and author of “I Am Part of the Resistance Inside the Trump Administration,” wrote that “many Trump appointees have vowed to do what we can to preserve our democratic institutions while thwarting Mr. Trump’s more misguided impulses until he is out of office.” Surely there is some virtue in this type of attachment to the Trump administration. Is it not possible that government officials could have been trying to thwart Trump's plans, to maintain order, from their public service posts?

After President Joe Biden won the election, I had conversations in which my peers explicitly endorsed the sentiment that non-Democrats are no longer needed in national politics and that bipartisanship is obsolete. With growing worry, I watched students and other Harvard affiliates endorse the view that any relationship with a Republican, or even a non-liberal, was a relationship with someone who was politically and morally irreconcilable.

In an Institute of Politics conversation with U.S. Representative Ayanna Pressley (D-Mass.), she said that “bi-partisan is a talking point. The goal is justice.” Justice, of course, is a necessary goal. Rooting out racism, sexism, and other forms of discrimination should be integral to any lawmakers’ vision. However, you can’t hop from wanting justice to achieving it. There’s a system of government; our politicians need to work with fellow legislators, especially when they represent half the country. Yet, Representative Pressley’s devaluation of bipartisanship, though cloaked in the name of justice, rejects the spirit of collaboration that this country was built on, and needs to uphold in order to make progress.

It feels like burning the bridge across the aisle is the new standard for Harvard political discourse. This is a grave disservice to students. Engaging with the opposition, rather than shunning them, is a positive any way you look at it. It gives students a chance to publicly criticize leaders they do not agree with and a chance to learn about a new perspective. If people continue to retreat further into their ideological camps, there is no future for this country and no road to reconciliation.

So cycling back to our 74 million Trump voters, are they all culpable enablers of the attack on the Capitol? While each and every Trump voter enabled the former president, I do not see this as equivalent to enabling the Capitol riots. While they may have enabled Trump’s problematic behavior, they could not all have anticipated such a drastic culmination of his presidency. While they voted for a divisive president, they should not be written off as criminals, complicit with Jan. 6.

It’s time to work with these voters again and to understand their frustration. Only then can we address the divisions in the country. Our newly-elected president said that “unity is the path forward” in his inaugural address. Unity is not spreading blame so far that we lose accountability; unity is moving forward and striving to find the common ground.

Carine M. Hajjar ’21, a Crimson Editorial editor, is a Government concentrator in Eliot House. Her column appears on alternate Wednesdays.

Have a suggestion, question, or concern for The Crimson Editorial Board? Click here

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.