News

Progressive Labor Party Organizes Solidarity March With Harvard Yard Encampment

News

Encampment Protesters Briefly Raise 3 Palestinian Flags Over Harvard Yard

News

Mayor Wu Cancels Harvard Event After Affinity Groups Withdraw Over Emerson Encampment Police Response

News

Harvard Yard To Remain Indefinitely Closed Amid Encampment

News

HUPD Chief Says Harvard Yard Encampment is Peaceful, Defends Students’ Right to Protest

The Rise of Student Research

Harvard continues to invest in improving and increasing undergraduate research opportunities, but with cuts to the federal budget, the supply of funds might not match growing demand

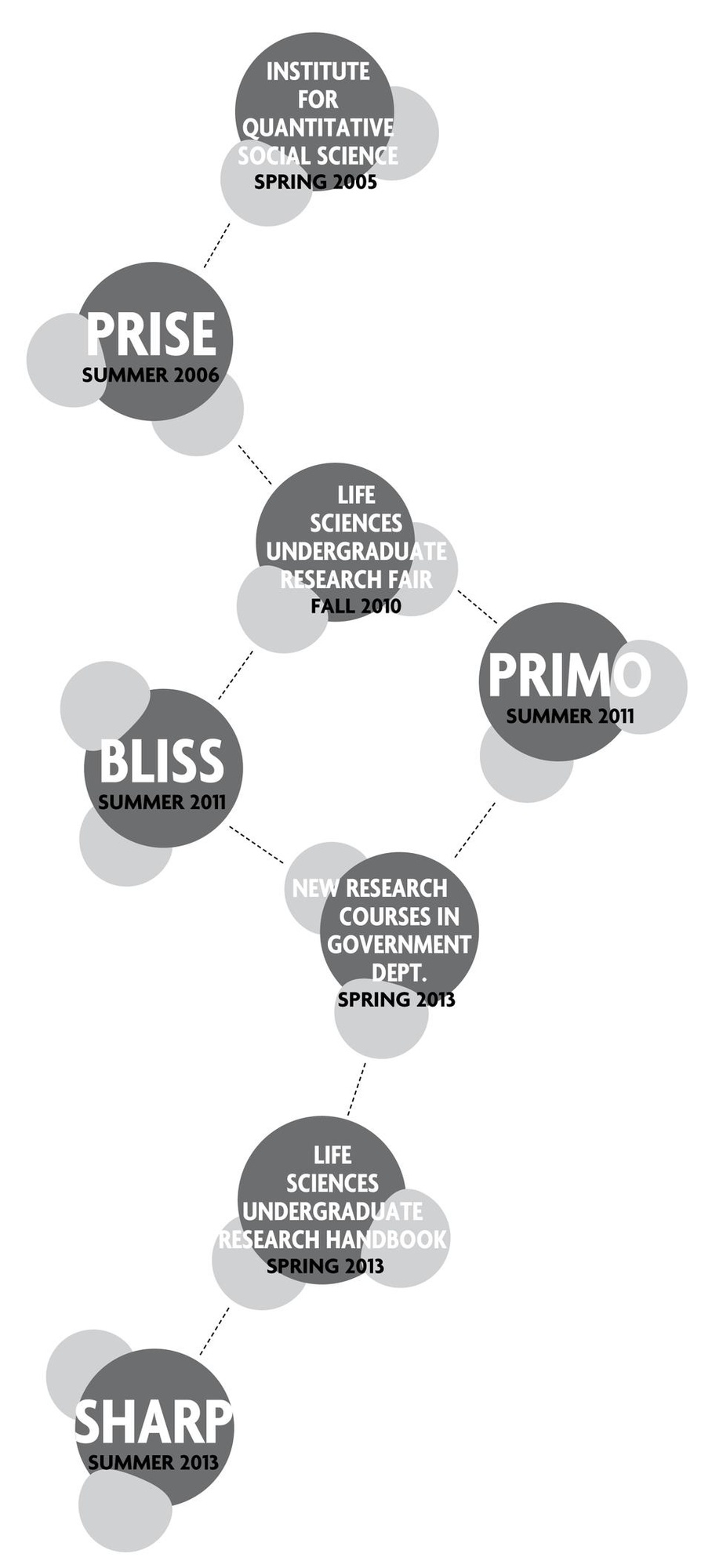

On June 10, 176 Harvard undergraduates will return to campus to participate in the Program for Research in Science and Engineering, the Behavioral Laboratory in the Social Sciences, the Program for Research in Markets and Organizations, and the Summer Humanities and Arts Research Program, ten-week summer research programs coordinated by the Office for Undergraduate Research Initiatives. These students represent less than half of the applicants, according to Gregory A. Llacer, research office director and PRISE coordinator, and just a small percentage of Harvard undergraduates who decide to pursue research during college.

Harvard has bolstered its investment in research through opportunities like those listed above and the Harvard College Research Program, which receives approximately 150 term-time applications for funding per semester and approximately 400 for the summer, according to Student Employment Office director Meg Brooks Swift ’93. Swift said the program typically funds about 80 and 70 percent of those requests, respectively.

Now, as Harvard sees some of its key research grants reduced by the federal sequester, which set funding cuts into motion on March 1 to reduce the federal budget deficit, University programs like the HCRP may experience greater demand as student interest in research continues to grow.

Nevertheless, students still see research as one of Harvard’s primary assets, and faculty and staff are confident the University will be able to match that interest.

“I think as long as students come in wanting that research experience, the pressure is going to remain on the institution to find ways, both from a faculty support as well as a funding perspective, [to support undergraduate research],” said Brooks Swift.

HARVARD’S “SELLING POINT”

Chemical and Physical Biology concentrator Richard Y. Ebright ’14 came to Harvard with some high school research experience, but his work through PRISE on a cancer drug discovery after freshman year and two more years of follow-up work in the same Harvard laboratory enhanced his desire to become a professional researcher.

Brooks Swift described access to top-quality research as Harvard’s “big selling point” for high school seniors like Ebright. And faculty and staff across disciplines are consistently striving to create—and publicize—new opportunities.

One of the major players behind this effort is Ann B. Georgi, an undergraduate research adviser for life sciences. Improvements under her tenure have included the introduction of the undergraduate research fair in 2010, which attracted about 250 mostly first-year students last fall, and the creation of an undergraduate research handbook, made available online and in print this year.

“I’ve seen more freshmen getting started in labs and finding the right lab in the beginning and just being happy there for four years, and that’s a huge advantage for a student because they become a fully integrated member of the lab,” Georgi said.

Assistant professor of government Ryan D. Enos, who will serve as a faculty sponsor for BLISS this summer, said that increasing data analysis and infrastructure demands in the social sciences have opened up new investigative possibilities for students outside of the natural sciences as well.

“As social science becomes bigger and bigger in terms of what we can do, we need more and more manpower. We can’t just do with graduate students and professors,” Enos said.

Two new courses in the government department and the Undergraduate Research Scholars program at the Institute for Quantitative Social Science, a Harvard-affiliated research institution established in 2005, offer students the possibility to learn about political science research.

Even the humanities, which traditionally receive limited support for research, have developed new opportunities like the SHARP summer research program, which engages ten students with interdisciplinary projects that range from philosophy to digital mapping.

FUNDING UNDER THREAT?

According to Georgi, most life science concentrators who submit “well thought-out and cogent [research] proposals” will receive support for their research from Harvard funds. But federal budget cuts that went into effect earlier this year as part of the sequester have already dipped into some of Harvard’s most important government grants, with the extended impact on undergraduate research left to be seen.

Rachelle Gaudet, professor of molecular and cellular biology and a member of the PRISE selection committee, said undergraduates will not necessarily be hurt even if laboratories do see their grants go down because supporting undergraduate research is “a fairly low-cost endeavor” compared to adding graduate students.

Nevertheless, a reduction in any kind of lab staff could have long-term effects.

“The capacity to host undergraduates is sort of limited by the presence of people who are able to, you know, supervise them day to day,” Gaudet said.

Brooks Swift said she thinks more students may apply for HCRP funding as opportunities like the Research Experiences for Undergraduates grants—a program funded by the National Science Foundation—are reduced as a possible result of federal cuts. Enos expressed similar concerns over limitations on NSF funding for political science projects.

Yet students remain optimistic about research prospects.

“I predict that funding for research will rebound in the future, and that this is more than likely a temporary reduction,” said Samuel F. Wohns ’14, a social studies concentrator and recipient of the HCRP grant for independent research. “Our country sooner or later will have to realize that funding for research, like funding for other programs that serve the public interest, cannot be slashed without serious consequences.”

FUTURE ON TRACK

Pursuing innovative research is one of the highlights of achieving professorial tenure, but as tenure positions become more competitive, so too will the market for new researchers, according to Enos.

“The ratio between people with Ph.Ds and tenured members is getting worse and worse,” he said.

But even if tenured opportunities are harder to come by, Enos described the alternatives as numerous, ranging from University-affiliated research institutions that employ non-tenured faculty members and students to the private sector, where startups and political campaigns are both sources of research jobs.

Gaudet also mentioned intellectual property law and science policy as professional paths in the life sciences.

Additionally, she noted that future professional prospects are hard to predict, because budget contractions and expansions are often cyclical.

“It’s quite possible that in five years things will pick up again,” Gaudet said, adding that she encourages her students to pursue research. “The time scale of establishing a career in the sciences is such that it’s not quite clear to an undergraduate what he will be after graduate school or a postdoc.”

—Staff writer Francesca Annicchiarico can be reached at fannicchiarico01@college.harvard.edu. Follow her on Twitter @FRAnnicchiarico.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.