News

Pro-Palestine Encampment Represents First Major Test for Harvard President Alan Garber

News

Israeli PM Benjamin Netanyahu Condemns Antisemitism at U.S. Colleges Amid Encampment at Harvard

News

‘A Joke’: Nikole Hannah-Jones Says Harvard Should Spend More on Legacy of Slavery Initiative

News

Massachusetts ACLU Demands Harvard Reinstate PSC in Letter

News

LIVE UPDATES: Pro-Palestine Protesters Begin Encampment in Harvard Yard

The Sophomore

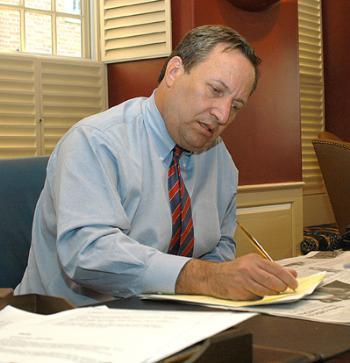

Summers sees success and consolidates power, but questions about effectiveness remain

Lawrence H. Summers rushed from meeting to meeting this year, his coterie of staffers struggling to keep up. More aides sweated away in the bowels of Mass. Hall, churning out briefing books by the ream. And these handlers and spokespeople lit up the University’s switchboards, following up on their boss’s latest whim.

This is the world of the Treasury Secretary turned University president, and this year, with his rocky start behind him, Summers began to produce some results. Trained in the D.C. jungle of red tape, the sophomore president was able to wield his authoritative, top-down style to productive ends.

Out of Summers' Mass. Hall office sprung several new deans, and with them new visions of the schools they were chosen to lead. He kicked off a much touted graduate student financial aid program that promises to help encourage public service around the university. And he did his best to mold Harvard to fit his executive style—taking steps to make the wildly decentralized and often chaotic University a little bit easier to lead.

But while Harvard may possess its share of red tape waiting for Summers’ shears, the University is no government agency. Summers has his superiors, the Harvard Corporation, to please. And he has his subordinates to help him execute his plans. But most of the University’s activities lie outside of this clear hierarchy—and in the hands of the faculty.

When it comes to his broader goals—the reinvigoration of the College, a focus on life sciences, and even planning for a new campus in Allston—Summers will need to have the faculty on board. Unlike the progress of the last year, Summers will not be able to order these objectives into being.

Summers has learned, to his frustration, some say, that universities do move at a different pace, as he’s found progress on his bigger goals to be slow-going.

But after another year at the helm, Summers still hasn’t proved whether he can persuade, push and cajole the faculty to rally behind his plans.

Navigating the Jungle

Summers didn’t begin his second year at Harvard with a completely clean slate.

The fall-out from his clash with former Fletcher University Professor Cornel R. West ’74—which dominated his first year—carried over from the spring.

But after Summers and new Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS) Dean William C. Kirby successfully lobbied the Chair of the Department of Afro-American Studies Henry Louis “Skip” Gates Jr. to stay at Harvard, that controversy subsided.

Summers continued to make waves, but his controversial moves were more deliberate and less distracting than last year’s Af-Am disaster, none coming to dominate his year.

In September, when Summers delivered a speech at morning prayers accusing some at Harvard and in the world of positions that were “anti-Semitic in their effect if not in their intent,” it was at the time and place of his choosing.

Summers, who publicized the speech heavily, seemed to have picked his battle carefully, and appeared satisfied with the mix of criticism and applause the provocative statements elicited.

Summers also drew scrutiny for his perceived influence in the English department’s November decision to cancel a poetry reading by Tom Paulin, whose works some consider to be anti-Israel.

But unlike the West debacle, both the anti-Semitism and Paulin debates faded into the background as the year progressed, allowing Summers to turn his attention to other areas.

“I think he’s toned down his rhetoric the second year,” said Kenan Professor of Government Harvey C. Mansfield ’53, a staunch Summers supporter.

Professor of Psychology Patrick Cavanagh, who wrote of “Ayatollah Summers” in a November letter to the editor in The Crimson about Paulin, has since eased his public criticism.

“I think he’s learning,” Cavanagh said last week. “I think he will lead Harvard into a great new era.”

Also in terms of the year’s internal turmoil, Summers managed to emerge with his hands relatively clean.

Though Summers was a strong supporter of course preregistration—defending it before undergraduates and telling them it was a done deal at House study breaks—he said its ultimate failure did not reflect on his year.

“Preregistration was FAS’s thing,” Summers said in an interview last month.

Indeed, little backlash was directed at Summers.

And though some College administrators said they saw Summers “pulling the strings” from the top, Kirby took full responsibility—and criticism—for the firing of Dean of the College Harry R. Lewis ’68 announced in March.

The result—a relatively smooth sail for Summers—allowed him to turn his focus to consolidating his power at the University.

King of the Jungle

Though his interactions with professors and students have resulted in the most public scrutiny, Summers’ chief policy initiatives have been designed within Mass. Hall and haven’t required much in the way of faculty support.

Picking four deans over the past two years, Summers has placed people who share his visions at the top of Harvard’s schools and in doing so has prescribed a direction for their future.

Ellen Condliffe Lagemann, who took the helm at the Graduate School of Education (GSE) last July, began a curricular review aimed at refocusing the mission of the school on K-12 education. While that review will require faculty mobilization, Summers’ contribution was in setting the school’s central priority.

In August, William A. Graham was promoted from acting dean to dean of Divinity School, and he too began a curricular review shaped by Summers’ call for more scholarly work.

Summers was quieter about his priorities for the Law School as he picked Elena Kagan to be its new head, but in his choice signalled that the school needs to seriously consider—as she has—the prospect of a move to Allston.

As Summers considers the College the heart of the University, he has been far more involved in FAS than other schools and articulated many of his priorities from the time of his arrival. Still, Summers used the appointment of Kirby to once again insist on the need for the College to revitalize itself.

On a more concrete level, Summers lists the creation of a heavily touted program to improve graduate student financial aid as among his successes of the year.

Summers will use $14 million in central administration funds to pay for fellowships primarily aimed at encouraging public service, in doing so fulfilling one of his installation speech pledges.

Though Summers communicated with deans to determine how each school would use its new aid money, the creation of the plan mainly required Summers’ prerogative and finances—not school-wide consensus or faculty support.

The plan bears Summers’ imprint—and title: the roughly 70 Presidential Scholars received his congratulations this spring.

Meanwhile, a more authoritative style than his predecessors has allowed Summers to make progress on the perennial goal of dealing with the fierce independence of the University’s autonomous schools.

In what would seem a relatively minor move, Summers implemented a change to fundraising policy that will encourage the University’s wealthiest alums to donate to priorities determined by the president. But the alteration to the so-called “class credit” system—which determines whether a given gift counts toward the total donation pool of a reunion class—was one proposed and beaten down in previous administrations. Schools with wealthier alums objected to the idea of sharing them with other parts of the University.

In pushing through an expansion of credit to “presidential priorities” he both brought the University closer together and increased his own power.

Summers cites as an accomplishment another unilateral move—the introduction of a new system of junior faculty appointment reviews by University Provost Steven E. Hyman—that will give the central administration a check on the academic direction of each school.

At the Kennedy School of Government, where the hiring of junior faculty was previously reported only to the Harvard Corporation, such appointments will now go through the Provost’s Office, Kennedy School Academic Dean Stephen Walt said.

Walt said he was unsure of the reasoning behind the shift.

“This was a decision taken between the Corporation and Massachusetts Hall,” Walt said. “The precise reason behind it, you’d have to ask them.”

Hyman said his new role in appointment reviews will depend on the school, but he will have the final approval for all junior appointments. The change allows him to “gather information on larger patterns, priorities, and challenges in faculty appointments,” he wrote in an e-mail.

These developments coming out of Mass. Hall are the successes of Summers’ direct style. But they also set Summers up for the future, putting in place mechanisms for further centralized and authoritative decision-making. He’ll have the money—next year will see a 10.4 percent jump in funding for the president and provost offices, and if it is successful, the class credit change will funnel more money his way. And his people are already in place—he has appointed a full one-third of the top deans in only two years and will have a close friend, rather than the rivaling strongman Lewis, in place as Dean of the College.

Waiting Game

Following on the heels of a soft-spoken, Renaissance-scholar president who inspired more sympathy than fear, supporters say the chief executive Summers brings a welcome sense of power and order to the table.

But as a man who is said to have won the presidency on the basis of his sweeping vision for the University, Summers needs to do more, to do big things.

He needs to watch over the once in a quarter century review of the College curriculum that will keep the University’s pedagogy a model throughout higher education. He needs to deliver on a promise to bring a greater focus on the life sciences to the University. And he needs to develop Harvard’s campus of the future across the river in Allston.

On these bigger issues, Summers isn’t going to be able to do it alone.

With the FAS curricular review, he can poke and prod, but ultimately a Faculty vote will usher in whatever change is to occur. Summers will have to go to the mat to wrestle out of wealthy donors the millions necessary to fund major new labs and cross-school collaborations, but the Faculty will need to be behind the initiatives for them to succeed. And while consultants, professional planners and administrators will design the ideal campus, the transition from blueprint to reality will require at least the grudging consent of the faculties that will call it home.

So far, Summers has yet to prove himself on these counts, and some suggest that he’s less comfortable with these consensus-requiring processes.

With curricular review, Summers was unable to order the process into action. While Summers said he understands that mobilizing the Faculty behind a curricular review takes time, others said he has been frustrated by the slow pace of the process.

Kirby wrote in an October letter that he hoped to have curricular review committees in place by the end of the first semester, but was unable to announce full committee rosters until May.

“I think his feeling is that the review should go faster,” Dean of Undergraduate Education Benedict H. Gross ’71 said of Summers. “But he understands that this is a complicated issue that will take time and that the Faculty needs to agree on it.”

And a University Hall source said the slow pace of change in general—and the need for consensus—has bothered Summers.

“Summers is very impatient, and wants to make decisions and have them implemented quickly, without a lot of consultation or even planning,” the source said. “He gets quite frustrated when he has made a decision and people continue to discuss and raise concerns or objections to the decision that has been taken.”

While Kirby succeeded in signing up several dozen professors to serve on the review committees—an accomplishment given the Faculty’s sometime aversion to administrative duties—there have been no clues whether or not Summers will be able to guide the Faculty toward his objectives.

With another of Summers’ top priorities—a push for new initiatives in the life sciences that would encourage collaboration between leading researchers at the Medical School, FAS and other Boston institutions—Summers has struggled to rally faculty to overcome their divisions. And some said he has been reluctant to engage faculty in a meaningful manner.

Summers has been promoting life science initiatives as “in the pipeline” since last year, but no progress has been announced. One proposal for a Harvard-MIT collaboration headed up by MIT Professor Eric Lander was reviewed by the Corporation yesterday, but Summers and Hyman refuse to comment on their plans.

“I can’t provide details on this matter right now since it remains an open topic of discussion among relevant faculty and administrators,” Hyman wrote in an e-mail.

Planning for these science initiatives is occurring mainly behind closed doors, and whatever faculty involvement there has been has been largely for show, several professors said.

One professor who sat on a committee that was studying possible initiatives last year said he knew about the proposal going before the Corporation this week, and was not surprised. The committee was not taken seriously by top administrators, especially Summers, he said.

“He’s more inclined to make decisions with perhaps less of the consultations and less building consensus, certainly than [former] President Rudenstine,” the professor said. “I think communications have been far from ideal.”

One FAS professor who has served on several committees agreed Summers has been reluctant to rely on faculty committees, a fact that has slowed progress on the life sciences initiatives.

“Summers seems to have less interest in using faculty committees than has been the practice in FAS,” the professor said. “He uses them mainly to get legitimacy, rather than input. But you can’t go very far in planning for the future of the sciences without involving faculty in a serious way.”

The jury is still out with regard to planning for Allston, another process taking longer than initially projected. One planner had suggested the University would have some direction by August, but officials have since said that date is not realistic.

Meanwhile planning proceeds in a number of venues, including a University-wide faculty planning committee. The committee has been receiving the reports of a pair of consultants studying issues related to the land in Allston, and the committee does remain a central body for faculty input. But planners say it is unclear whether the committee will continue its work next year, and in what form.

A number of the University’s schools have created their own planning processes and faculty committees to study the issues at their particular schools. These committees report to the schools’ deans, not Summers, underlining that despite efforts to centralize planning for the future campus, the various faculties will have to play a role.

Two years ago the Law School faculty nearly unanimously voted to reject the idea of a move, and it’s unclear whether Summers has worn down their opposition.

The test will come after Summers makes the internal decision of who will move, and then has to go out to sell the plan.

Leader of the Pack?

Though Summers has yet to realize many of the broader initiatives he has set forth, professors across the University disagree on whether they think he possesses the skills necessary to build consensus.

When Summers began involving himself in schools’ affairs last year, he was seen as aggressive, outspoken and relentless—and some say this earned him the respect of faculty.

Conant Professor of Education and GSE Academic Dean Judith D. Singer said that Summers’ propensity to take a stand may yield both friends and enemies.

“Larry has strong views and he lets his views be known...This means that not everyone will always agree with him,” Singer wrote in an e-mail. “However, I believe that many faculty respect him precisely because he is willing

“He certainly became well-known for his intrusion and micromanagement,” Cavanagh said.

But Cavanagh said he has since noticed a change in the president’s style which may enable him to garner more support. “I don’t see him doing that now, not that he won’t turn up and do something again,” he said.

Others argued that Summers’ style changed little, but that in this second year of his presidency more people grew accustomed to it.

According to Ramsey Professor of Political Economy at the Kennedy School Richard Zeckhauser ’62, a long-time friend of Summers, more people take the president’s aggressive style as given—making them less reluctant to back his views.

“My guess is he has changed his style slightly, but I think what has happened is more people have just gotten used to his style,” Zeckhauser said.

And those who have not quite grown accustomed to Summers’ authoritative nature may choose to support him out of fear, some professors said.

“He’s got this very aggressive style, which I think is sometimes frightening, especially to junior faculty,” Business School Professor Louis T. Wells said.

Mansfield agreed that the president’s agenda has not been seriously questioned, despite the verbal attacks on Summers following some of his gaffes.

“Though a lot of the faculty may be wary of him, no one has challenged him, particularly after the Cornel West incident,” Mansfield said. “He is an imposing intellectual figure, he’s not a person you can argue down and dismiss.”

But Summers’ style “certainly can make things more difficult,” according to the professor involved in the life sciences initiatives.

“I think he’s starting to get more used to how Harvard works, but in the end, the faculty has to be enthusiastic and involved,” he said. “Otherwise, things don’t get going.”

—Staff writer Jenifer L. Steinhardt can be reached at steinhar@fas.harvard.edu.

—Staff writer Elisabeth S. Theodore can be reached at theodore@fas.harvard.edu.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.