News

Progressive Labor Party Organizes Solidarity March With Harvard Yard Encampment

News

Encampment Protesters Briefly Raise 3 Palestinian Flags Over Harvard Yard

News

Mayor Wu Cancels Harvard Event After Affinity Groups Withdraw Over Emerson Encampment Police Response

News

Harvard Yard To Remain Indefinitely Closed Amid Encampment

News

HUPD Chief Says Harvard Yard Encampment is Peaceful, Defends Students’ Right to Protest

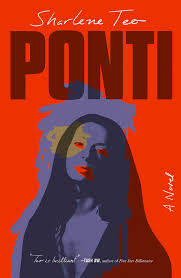

‘Ponti’: A Spin on Your Classic Coming of Age Novel

3.5 Stars

What seems like a typical coming-of-age novel about a high school teen struggling to fit in transforms into a complicated story filled with teenage rebellion, familial conflicts, and Singaporean culture. “Ponti,” a novel written by Sharlene Teo, follows three Singaporean women, Szu, Circe, and Amisa, who struggle in a cutthroat environment that heightens their insecurities.. Szu is Amisa’s only daughter, and a major disappointment in Amisa’s eyes. Whereas Amisa is a stunningly beautiful, retired actress who enchants almost every man with just her looks, Szu is the typical coming-of-age character: unattractive, overweight, and unliked by her peers. She has only one friend, Circe, another misfit who plays an important role in Szu’s dark childhood. The story, while including unique turns that reveal that these characters are not one-dimensional, remains mundane and like many other young adult novels. The story has an unoriginal plot about the life of three different women prevalent in many young adult novels, but the plot reveals that these characters are not as one-dimensional as they seem and struggle through their own internal conflicts.

The novel starts as young adult novels often do: A young teenage girl who finds herself, yet again, in a position of shame in a social setting. Immediately, Teo introduces themes of insecurity and constant comparison between the main character and those that surround her. She desperately wishes to be like other girls, with boyfriends who go on group dates to the movies. “Ponti” brings up rather superficial topics of beauty and wealth through the contrasts between characters. Much of the book talks about how Amisa and Szu have been treated based on their looks. On one hand, Amisa is offered a role in a movie while working in a movie theater and on the other hand, Szu is rejected by her mom because of her weight. However, as the novel continues, it’s clear that there is more to these relationships than pettiness or simple rivalries. The underlying tensions can be characterized with layers of trouble that have been brewing for a long time, something that keeps the novel interesting and new.

Teo’s decision to simultaneously switch from first person to third person, between characters as well as between time periods, creates a holistic understanding of the characters. Amisa isn’t just the critical mother nor is Circe Szu’s supporting sidekick. The shift between past and present could be confusing but instead, Teo finds a way to utilize cliffhangers and plot reveals to keep the reader interested. The way the reader is forced to piece all of these memories mirrors Circe’s and Szu’s respective points of view as they themselves try to remember everything from their past. This adds to the suspense, making it more enjoyable, and allows the readers to get attached to the story.

The most refreshing aspect of this novel is how Teo writes about her depiction of a Southeastern Asian experience which veers far from the stereotypes seen in many other novels. Teo, who was born in Singapore, writes about the everyday lives of women in Singapore, a daily life that is extremely relevant to teenage girls, despite its cultural specificity. How Szu and Circe “take the train to Bugis, but the movie [they] want to see is sold out so [they] buy giant cups of Diet Coke and sit by the giant pillars in the cinema lobby because this is habit,” seems to mirror a simplistic and relatable life. On the other hand, Teo also cleverly mentions Bugis, an area that was once known for its large shopping complex, restaurants and nightlife, but is now a popular spot for Singaporeans rather than tourists. As they experience their ups and downs, the continuation of these routines seems almost necessary and their interactions are genuine in their own way. So, while Teo does not bombard the novel with Singaporean specialties and it is easy to forget that this takes place in the Eastern Asian country, it is realistic in the way that everyone’s life can be generalized: Not every culture is specific to their most commonly known customs.

“Ponti” can be both a quick read and a thought-provoker. There is both a lightheartedness and a sincerity that seems to make the novel a page turner and rather easy to read. “Ponti” may seem slow, generic, or typical at first glance, but the secrets that are uncovered about why Amisa is so cold-hearted and distant, and how these untied ends are resolved, are far more engaging than other coming-of-age novels.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.