News

Progressive Labor Party Organizes Solidarity March With Harvard Yard Encampment

News

Encampment Protesters Briefly Raise 3 Palestinian Flags Over Harvard Yard

News

Mayor Wu Cancels Harvard Event After Affinity Groups Withdraw Over Emerson Encampment Police Response

News

Harvard Yard To Remain Indefinitely Closed Amid Encampment

News

HUPD Chief Says Harvard Yard Encampment is Peaceful, Defends Students’ Right to Protest

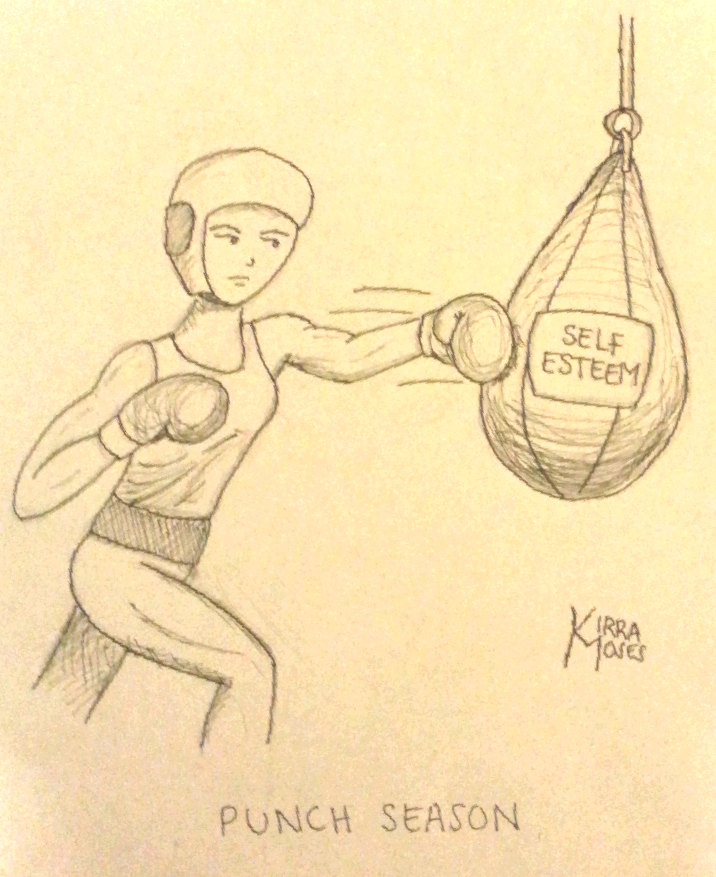

You Can Punch If You Wanna

But if your friends don’t punch, then they’re still friends of mine

I lost punch.

Of course, to lose a game, you have to play it in the first place (which is why I avoid beer pong at all costs). And punch is a game, after all.

Think about it. One must conduct oneself according to a carefully outlined set of rules, some spoken and some not. Take the dress code, for example—a guideline to which an aspiring club member must adhere as loyally as humanly possible. “No heels, please,” no problem, thanks. That’s an easy enough instruction to follow. But “casual chic” offers no clearer direction than would “nice clothes,” and an invitation that mandates “cocktail casual” attire would do just as well—and just as oxymoronically—to require that hopefuls arrive in “ballroom sleepwear.” Add explicit requirements like these to a host of implicit dos and don’ts (do smile until your cheeks hurt, don’t mention that you write for The Crimson), and you have your parameters of play.

Then there’s the competition. And this isn’t a soccer match: This is cross-country. Not just because it takes as much endurance to girl-flirt for an hour straight as it does to pound through eight kilometers of hill and dale, but also because your teammates aren’t just teammates; they’re rivals, too. That’s not to say that your friends will stick their legs out to force you off the course and into a ditch with a twisted ankle. But their winning does not necessarily lead to your winning. No one player carries the team on her back. Each runner alone puts one foot in front of the other to reach the finish line. And when you earn a medal, it means someone else does not.

So punch is a game, and I joined in. I pulled back my arm and took a swing. I missed by a mile, and I felt sad. That’s one of the problems with punch, of course: It can introduce or reinforce the idea that a select group of older Harvardians may determine a select group of younger ones’ worth. Final clubs also will never shed their air of elitism, a vestige of the notorious Old Boys’ Club Harvard of yore, even though they now can boast substantial racial and socio-economic diversity.

It’s dangerous to punch thinking that success translates into grabbing the highest stone on a social rock wall or that failure signifies the first step toward pariahdom. It’s also dangerous to punch thinking that you must change your behavior or disguise your background in deference to the imaginary refined, blue-blooded punch powers that be. But if you punch knowing that a final club would be just one added dimension to your life at Harvard, just something you want to join because why not, then who’s to tell you you’re in the wrong? No, we should not be ashamed of lacking wealth, of appearing uncultured, of any of our mannerisms or traditions. But we also should not be ashamed of seeking to belong to something.

Belonging is as fundamental a human desire as food and shelter. We find belonging in a host of places: In our blocking groups, our relationships, our sports teams, our newspapers and literary magazines and theater troupes and service groups and fraternities and sororities and, you guessed it, final clubs. Perhaps the forces of racism, sexism, and exclusivity can permeate the final club scene, and perhaps some club members do feel superior to the masses that line up at their doors. But that doesn’t mean that most sophomores who choose to punch do so to foster a great schism between the haves and have-nots. We punch to belong, and there’s nothing wrong with that.

Thankfully, Harvard presents enough opportunities for belonging that final clubs do not even come close to ensuring or endangering student happiness. That’s why the disappointment of losing punch, while sharp at first, fades away with time and a few tea lattes. I did not—do not—think I am better than punch, and I also do not think punch is better than me. Punch is just punch, nothing more and nothing less. None of us needs it. But neither should any of us feel guilty for wanting it.

Molly L. Roberts ’16, a Crimson editorial writer, lives in Cabot House. Her column appears on alternate Mondays. Follow her on Twitter at @mollylroberts.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.