What Critical Race Theory Was — and is — at Harvard Law School

Former Harvard University President Derek C. Bok vividly recalls the day that he, then dean of Harvard Law School, flew to California to recruit Derrick A. Bell Jr. to the Law School’s faculty in 1969 — more than five decades ago.

“We had gradually developed a fairly substantial number of Black students in the Law School, and we had nothing in the curriculum about the role of race in the law as it affected a number of fields of law,” Bok said.

“There was nobody really in a position on the faculty that could relate in ways that only a Black professor at that time could really understand and help with,” he added.

Bell became the Law School’s first tenured Black professor in 1971 and called for the school to diversify its faculty. In 1990, Bell took what he called a “leave of conscience” — a voluntary unpaid leave of absence — and said he would not return until the Law School hired its first Black female tenured professor.

The school, however, did not do so until 1998, leading Bell to ultimately forfeit his tenure in 1992, spending the rest of his career at New York University.

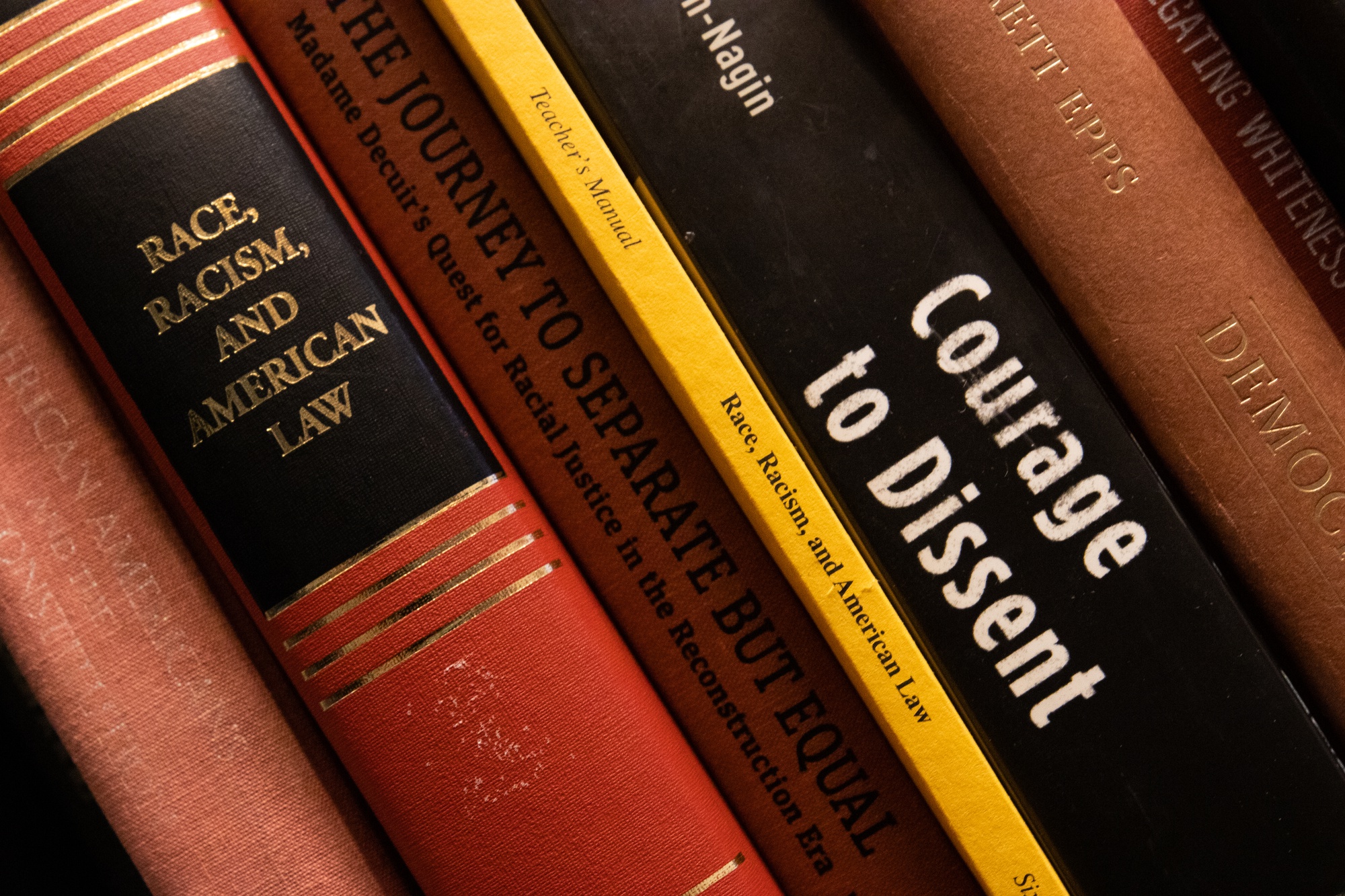

While at Harvard, Bell published the casebook “Race, Racism, and American Law,” which — as he wrote — was motivated by the question, “What does it mean to say that racism is a permanent feature of American society?” Much of his work aimed to address this issue, studying how racism had been incorporated into America’s legal framework.

Bell’s scholarly work and writings are widely credited as being foundational works of critical race theory, a field of legal scholarship that has become a lightning rod for conservative backlash in recent years. Multiple state legislatures have limited the teaching of critical race theory in public schools, and several more are considering laws that would do the same.

A number of Republican politicians — including Florida Governor and Law School alum Ron DeSantis and former Vice President Mike Pence — have publicly condemned critical race theory, with DeSantis tweeting that it is “state-sanctioned racism.”

Legal scholars, however, say that the political attacks and laws against critical race theory are baseless and misrepresent what the term actually references.

“These statutes are — in some fundamental sense — ridiculous, that they’re aimed at a nonexistent target. A second version of that point is the people who are supporting these statutes have literally no idea what critical race theory is,” said Mark V. Tushnet ’67, professor emeritus at Harvard Law School. “It’s just a label they’ve attached to ideas that they don’t like, ideas about the importance of race in U.S. history for example. The word I use is fundamentally silly.”

Rather, to legal academics, critical race theory is a school of legal thought that seeks to examine how the concept of race is codified by the law and the consequences of these codifications, such as systemic racial inequality.

Bell and a number of Harvard Law School alumni — including University of California, Los Angeles and Columbia University law professor Kimberlé W. Crenshaw, who is credited with coining the term, and University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Law School professor Mari J. Matsuda — are considered to have been instrumental figures in critical race theory’s development.

How has this legal field been shaped by Harvard Law School and how do its students and scholars view conservative attacks on the field?

‘A Splinter Conference’

Many of critical race theory’s pioneers passed through the Law School on their scholarly journeys.

While at the Law School, Crenshaw and Matsuda were engaged in organized discussions on critical race theory, which called on the school to increase diversity among its faculty and to better incorporate race into the school’s curriculum.

In 1983, Crenshaw and Matsuda led a group of Law School students in organizing an “Alternative Course” called “Racism and the American Law.”

The 14-week project — based on Bell’s “Race, Racism, and American Law” — was supported by proponents of critical legal studies on the Law School’s faculty and invited visiting professors from other law schools to teach at the school. More than 100 students attended the “Alternative Course,” one of the goals of which was to call on the Law School’s administration to offer an official course that studied race in the law.

Critical legal studies — a prominent legal movement of the 1970s and 1980s that was especially influential at Harvard Law School — sought to study the relationship that the law had with social and political issues.

Critical race theory emerged as an offshoot of the critical legal studies movement after the originators of critical race theory contended that critical legal studies and other legal approaches of the time failed to properly examine the relationship between race and the law.

“Critical race theory originates in kind of a splinter conference that breaks off from the general CLS conference,” said Robert W. Gordon ’63, professor emeritus at Yale and Stanford law schools and a former Crimson Editorial chair. Gordon was one of the original scholars of critical legal studies.

As Crenshaw wrote in her 2011 Connecticut Law Review article “Twenty Years of Critical Race Theory: Looking Back to Move Forward,” 24 scholars attended a 1989 conference at the University of Wisconsin called “New Developments in CRT” — which Crenshaw added represents the first use of the term.

Among the event’s participants were Bell and several Harvard Law School graduates — including Crenshaw, Matsuda, Western State College of Law professor emeritus Neil T. Gotanda, University of Buffalo Law School professor emeritus Stephanie L. Phillips, and others — a number of whom first interacted with critical legal studies at Harvard and met during their time there.

These academics, characterized by Crenshaw as “a motley crew of minority scholars” who attended the “backdoor speakeasies” of American Association of Law Schools and critical legal studies annual meetings, hoped to “move beyond the non-critical liberalism that often cabined civil rights discourses and a non-racial radicalism that was a line of debate within CLS.”

In the years since critical race theory’s inception, Harvard Law School has incorporated critical race theory and other approaches to the law related to identity — such as feminist legal theory — into courses in its curriculum, though many argue the school has not gone far enough in these efforts.

Institutional Support

Today, Harvard Law School offers two courses focused on critical race theory. This past fall, Law School professor Kenneth W. Mack taught a course titled “Critical Race Theory” and this past spring, Law School professor Guy-Uriel E. Charles taught a seminar called “Critical Race Theorists and their Critics.”

For Charles, teaching the seminar was appealing because he wanted “to try to understand why critical race theory was viewed as so controversial.”

“When I first started, it was focusing as much on ‘What is critical race theory?’ as ‘What [do] the critics of critical race theory think that it is?’” he said. “This semester, when I’ve taught it, I’ve focused much, much less on the critics.”

Charles added that conservative criticisms of critical race theory have factored into how he teaches the class, saying that “part of the focus of my class is to make sure that my students have a pretty good understanding about what critical race theory is.”

“Just to give a basic example, critical race theory is not diversity, equity, and inclusion — DEI — those are just two different things,” he said. “It doesn’t mean that they’re necessarily incompatible — doesn’t mean that they are or they are not incompatible — it just means that they’re different things.”

When asked if the conservative attacks on critical race theory had impacted its teaching and study at Harvard, Law School professor Jon D. Hanson answered, “Mostly no, but a little bit yes.”

“The ‘mostly no’ has to do with the fact that there isn’t any direct prohibition or attempt to prohibit what is taught in schools here in Massachusetts, much less law schools,” Hanson said of teaching critical race theory. “I can’t imagine a school like Harvard capitulating to pressure not to do that.”

“On the other hand, I would say, it is striking to me that, as an institution from which we could say critical race theory emerged and an institution that purports at this point to value the insights of critical race theory, I think it is striking how quiet we have been about what could be described as fascist trends in this country,” he added.

Boston University School of Law professor Aziza Ahmed said when she taught a seminar on critical race theory at Harvard Law School in spring 2021, she wanted her students to “understand what the background rules — legal rules — and structural conditions were that essentially contribute to the ordering of society along racial lines.”

Ahmed — a graduate of Harvard’s School of Public Health — said she was also interested in “how science gets mobilized in the context of law to essentially make racial claims,” which motivated her selection of cases to study in the class.

Sean R. Wynn, a rising second-year student at the Law School who took Charles’ class, said he enrolled because he had just one slot for an elective and “wanted to take something that was as far away from a doctrinal class as possible.”

“It was really good over the past five months to just be challenged on the way that I see the world,” Wynn said.

‘Disappointed in the Curriculum’

But some affiliates say the Law School’s most fundamental courses — its required first-year curriculum — fail to challenge students along these lines.

Student efforts to incorporate critical race theory into the curriculum and discourse at the Law School have continued since the “Alternative Course,” including student-run conferences, teach-ins, and protests in recent years.

One example of this is the Bell Collective, a student organization at the Law School — named after Bell, the former Law School professor — that organizes an annual critical race theory conference. Edward S. Chung, the Bell Collective’s incoming president and a rising third-year student at Harvard Law School, joined the group after feeling disheartened by the school’s first-year curriculum.

“I was kind of disappointed in the curriculum that they had in terms of how they approached race and other topics,” Chung said. “So, a few of my mentors reached out and said you should join the Bell Collective, we had the same issue you had our first year, and this is how we decided to deal with it and make our own conference to address these issues that weren’t being covered in the curriculum.”

Law School spokesperson Jeff Neal declined to comment on criticisms that the school’s first-year curriculum focuses too heavily on doctrine and fails to properly address race and identity.

In recent years, as political attacks on critical race theory have increased, Chung said he feels the nine-member Bell Collective has received increased attention at the school.

“The support the conference is getting has changed a little bit, from more left-leaning or smaller communities within the Harvard Law community,” Chung said. “Now, it’s like the institution is trying to take a heavier hand or like a bigger role in the conference because of the attacks and because of the buzzword that’s been going around in a sense.”

According to Noah Q. Spicer, a rising second-year student at the Law School who took Charles’ class, not talking enough “about how doctrinal issues or black letter law intersects with our various identities” is a missed opportunity for the Law School’s first-year curriculum.

“Harvard Law School produces some of the most notable figures in not only American history, but world history, and so, I think not talking about how our identities play a role in how decisions are made within the courtroom and how it impacts people’s lives doesn’t allow us to interrogate those views and to really refine how we feel,” Spicer said.

“Some people might deny or not feel like race plays a meaningful role in how the law is adjudicated, that judges and lawyers are facially neutral and look at the law from a sanitized perspective, but I just don’t think that that’s reality,” he added

Ahmed, the BU law professor who was a Harvard visiting professor, said that she feels there is a need to incorporate discussions of race and identity into the first-year law curriculum.

“I think it’s not just critical race theory,” Ahmed said, referencing other approaches to the law examining identity. “The concern is becoming more immediate because the Supreme Court — especially if you’re teaching a class like Constitutional [Law] — is so out of sync with what most Americans want and certainly what most law students want.”

“You have to be able to bring in a broader conversation about power and politics and interest groups,” Ahmed added. “That necessarily requires an acknowledgment of the types of inequalities we see in society.”

—Staff writer Neil H. Shah can be reached at neil.shah@thecrimson.com. Follow him on Twitter @neilhshah15.