A Witch’s Hex on the Harvard Name

In February 1692, the tale of two young girls experiencing unexplained fits spiraled into rumors of witchcraft in Salem, Mass. The hysteria consumed the small town, resulting in a series of prosecutions and executions that would cement Salem’s infamous legacy for centuries.

Some 200 men, women, and children faced accusations of witchcraft, and a special court convened in Salem to hear their cases. Over the course of a little more than a year, 20 executions took place at the order of the nine judges sitting on the court.

Though Salem is 20 miles north of Cambridge, the trials did not occur without the influence of Harvard’s then-president Increase Mather, class of 1656.

Mather — the namesake of one of Harvard’s 12 undergraduate Houses — has recently come under scrutiny as residents of Mather House interrogated his legacy in a 2016 archival project. The Puritan minister owned a slave on campus in addition to playing a role in the Salem witch trials.

Though he held one of the most powerful positions in the colony at the time, Mather was not the sole Harvard man implicated in the witchcraft calamity. Included in this infamous cast were Nathaniel Saltonstall, class of 1659; Samuel Sewall, class of 1671 and a member of the Board of Overseers; and University treasurer John Richards, who all served as justices on the special witchcraft court.

Finally, presiding over this court was William Stoughton, class of 1650, a key Harvard donor and namesake of Stoughton Hall. Self-appointed advisor to this court was Cotton Mather, class of 1678.

The Influence of the Mathers’ Scholarship

Cotton Mather, a Puritan minister and prolific author, began his scholarship on witchcraft years before the trials commenced. He suggested that the devil had a presence in the colony in his 1689 book “Memorable Providences, Relating to Witchcrafts and Possessions,” which recounts strange happenings within a Boston family whose housekeeper was eventually hanged for witchcraft.

In a 1994 interview, Folklore and Mythology chair Stephen A. Mitchell said Cotton Mather was “personally responsible” for the hanging of the alleged witch. Cotton Mather’s book has been cited by scholars as a major influence on the trials in Salem, and no wonder: “Memorable Providences” calls for the “Detection” and “Destruction” of those who allegedly practiced witchcraft.

Despite his incendiary rhetoric, Cotton Mather did caution the judges on the special witchcraft court against convicting a defendant solely on the basis of spectral evidence — evidence based on dreams and visions.

On June 15, 1692, soon after the court began hearing trials, Mather authored a report co-signed by several other ministers — including his father — that urged for “exquisite caution” in the proceedings. The report, however, did not go so far as to condemn the trials; indeed, it called for the “speedy and vigorous prosecution” of the witches.

In October 1692, Increase Mather published his own work titled “Cases of Conscience Concerning Evil Spirits,” which cautioned against the use of spectral evidence. He delivered the paper as a formal address to his fellow ministers, received their endorsement, and passed the work off to the governor for consideration.

“It is better that ten suspected witches should escape than that one innocent Person should be Condemned,” Mather wrote.

By the time this was published, however, the 20 executions had already taken place.

Increase Mather’s lateness to speak on the trials was not calculated, but rather the accidental byproduct of larger political schemes. Mather had been abroad in England for the entire spring, engaged in negotiations with the Crown over the colony’s recently revoked charter.

Alyssa G. A. Conary, co-founder of the Salem Historical Society, says the Mathers are frequently mistaken as the central figures in the administration of the trials.

“I think that there's sort of this popular idea of New England being a theocracy, of the Mathers dragging people off to jail,” Conary says. “They had no legal power, really. They're commenting on it, and they're giving the judges advice.”

“The Mathers are usually cast as arch villains in the story,” she adds. “But I think people think that they're more extraordinary than they actually were.”

Conary says the major “overlooked” players in the trials were judges such as Richards, Sewall, and Stoughton.

‘Out for Blood’

Chief amongst these “overlooked” judges was Willian Stoughton.

Increase Mather recommended that Stoughton, a friend of Cotton’s, assume the role of lieutenant governor in the colony in 1692. Stoughton’s newfound prominence in that role landed him a seat as the chief justice of the special witchcraft court that same year.

“I think Stoughton was out for blood,” Conary says.

He was a zealous — perhaps overzealous — justice; once, he commanded the jury to redeliberate after they found a 70-year-old woman not guilty. They reversed their verdict, and she was hanged.

Then-Massachusetts Governor William Phips disbanded the courts in October 1692, but Stoughton continued his crusade: He signed eight death warrants, even after the court had been dismissed. Phips halted the executions in 1693.

“When they shut down the court in 1693, he’s furious; he storms out of the room,” Conary says. “For me, personally, I really see him as one of the arch villains.”

Years after the trials, former University President Josiah Quincy, class of 1790, who resided in Stoughton Hall during his time at the College, penned a book detailing Harvard’s history. In it, he condemned the conduct of his former dorm’s namesake.

“If it were possible, it would be grateful to throw the mantle of oblivion over the part acted by Stoughton in that tragedy. But the stern law of history does not permit,” Quincy wrote.

As the chief justice, Stoughton never apologized for his role in the trials. But Sewall, a presiding judge, did issue a public apology in January 1697, which was read aloud at an event in Boston to memorialize those executed as a result of the trials.

“Samuel Sewall desires to take the Blame and shame of it, asking pardon of men,” the apology read. None of the other eight justices apologized — though Saltonstall resigned from the court, after becoming “dissatisfied” with the proceedings, according to a letter by Thomas Brattle, class of 1676, in which he condemned the witchcraft court’s haphazard methodology.

Despite Stoughton’s harsh comportement both during and after the trials, he became a key benefactor to Harvard. In 1698, he donated a thousand pounds for the construction of a new residence hall in his name. It was completed the following year.

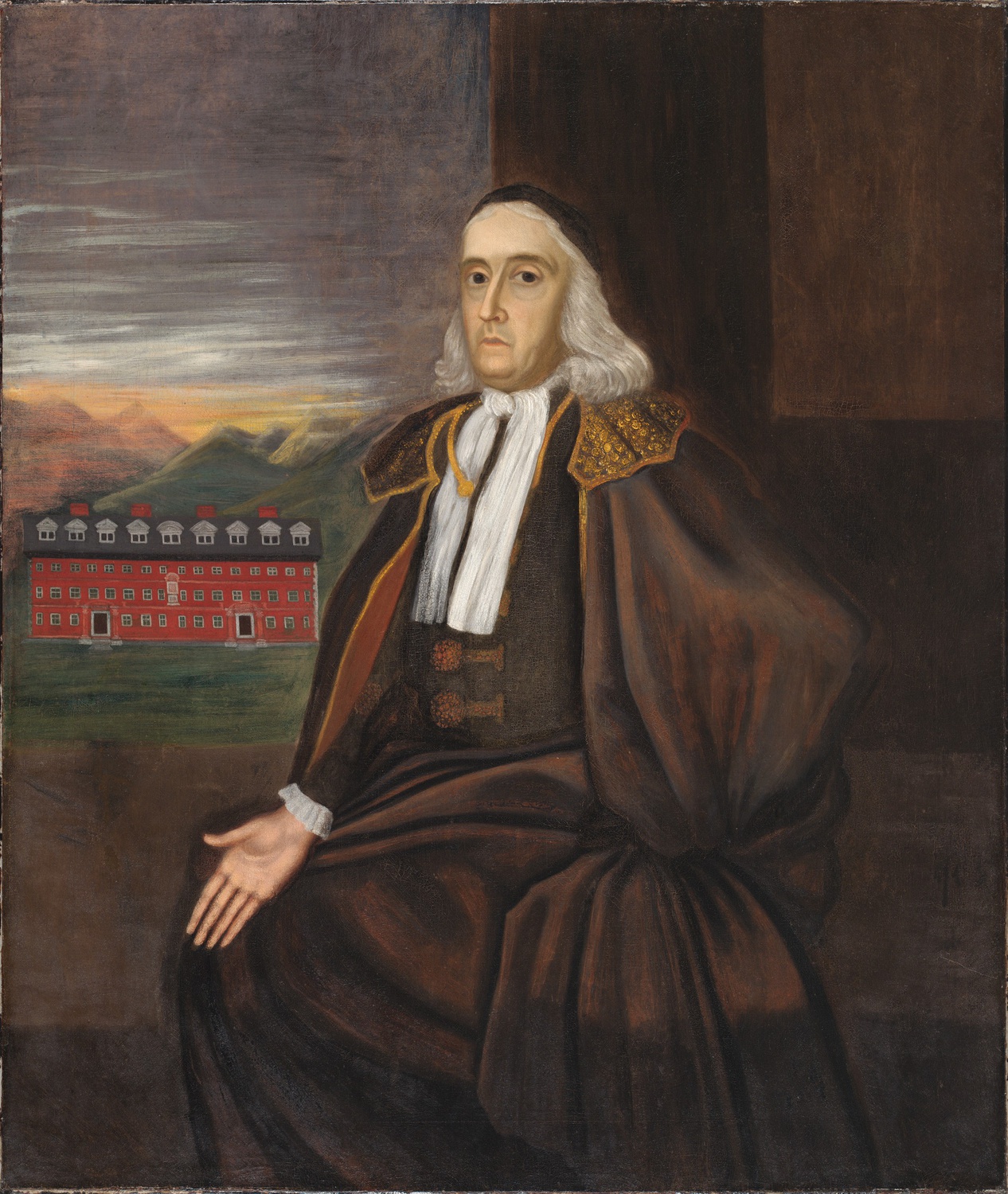

The original Stoughton Hall — “an unsubstantial piece of masonry,” according to records — was razed in 1780 and replaced by a more stable successor of the same name. The original structure still stands in the background of Stoughton’s portrait, which hangs now in the faculty room of University Hall.

But despite “his noble donation to Harvard College,” Quincy wrote, “there is no class of public men, towards whom history should be more inexorably severe than to those, who, through fear, passion, or policy, lend themselves to popular excitements.”