News

Pro-Palestine Encampment Represents First Major Test for Harvard President Alan Garber

News

Israeli PM Benjamin Netanyahu Condemns Antisemitism at U.S. Colleges Amid Encampment at Harvard

News

‘A Joke’: Nikole Hannah-Jones Says Harvard Should Spend More on Legacy of Slavery Initiative

News

Massachusetts ACLU Demands Harvard Reinstate PSC in Letter

News

LIVE UPDATES: Pro-Palestine Protesters Begin Encampment in Harvard Yard

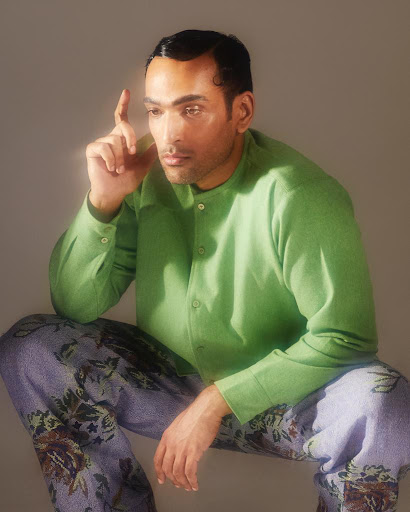

‘Pehla Qadam:’ Global Stardom and the Future of Diasporic Art with Pakistani Musician Ali A. Sethi ‘06

Singer and composer Ali A. Sethi ‘06 recently returned to campus to perform at the Mittal Institute’s celebration of 75 years of Pakistani-Indian “azadi,” or independence from British rule on Sep. 14. At his campus appearances his musical genius, political reflections, and inviting charm were on full display.

“I’ve started saying this like a mantra: folk is woke. Especially as brown kids, we’re often searching for what we can tap into in our ancestral culture, in our inheritance, something that can nourish our contemporary consciousness and quest for an identity that feels whole, yet liberated,” Sethi said in an interview with The Harvard Crimson, reflecting on his process as a writer and artist of color. “I find that folk traditions of South Asia are some of the most flexible, fluid, mystical, philosophically supple traditions in human history. That’s what my undergrad years at Harvard taught me. That’s what my immersive apprenticeship in Hindustani classical sangeet taught me. That’s what my understanding of poetry has taught me. And that’s what my life has taught me.”

Sethi is known for his skill in amalgamating Hindustani raga with contemporary, Western beats and harmony. In the interview, he talked about growing up when the internet was still nascent, in the unique musical sphere of Lahore in the late ‘90s and early 2000s.

“There was music of the Sufi shrines in the city, a very vernacular form of music,” Sethi said of Lahore and its influence. “There was Bollywood music coming in, and there was the azaan [Islamic call to prayer] which you would hear five times a day. But at the same time there were cassettes and CDs, random bits of Western pop music, that would flood the bazaars.”

He recalled a moment in his early childhood, when he picked up a RuPaul CD that had found its way to a Lahori bazaar. “I had no idea who RuPaul was, but I picked it up, I listened, and I was immediately like, ‘This is me, this is my jam,” he said. “I was going around the house saying ‘shantay shantay!’”

Indeed, Sethi attributes his sound today to being immersed in this unique musical environment and to the fact that he did not have formal musical training until the age of 17. “I just played the hell out of all this music, and learned it by heart. I would recite bits of alaap from a qawwali, or a bit of a Bollywood song from an audio cassette — it was all happily mixed up for me,” Sethi said. “Now is the first time in my life that I’m starting to become more aware of the difference in music theories of Western and Eastern sound. But even still, I find myself constantly mixing things up…and that’s something I don’t want to lose.”

Sethi musingly reflected on the creative process behind his song, “Khabar-e-Tahayyur-e-Ishq,” or “The Astonishing Tale of Love.” Penned by 18th century Urdu poet Siraj Aurangabadi, this ghazal is traditionally performed in qawwali form, as a sort of call and response. But Sethi’s rearrangement is wholly something new: The instrumentation, produced by frequent collaborator Noah Georgeson, features emotive strings, harp, and Sethi’s voice in an expansively haunting range. Its composition amalgamates and inverts genres; in a way that even Sethi could not quite wrap his head around. “I think I was channeling a bit of raga and I think I was channeling a bit of Jeff Buckley’s version of ‘Hallelujah,’ too,” he said. “There’s a place where they meet in my brain. Professor [Ali] Asani sent me the poem and the story of the poet.” As he trailed off, he began to hum the melody for “Khabar.” It became clear that his music-making process is organic and spiritual; the music flows out of him.

“Yakjehti Mein,” or “In Solidarity,” is another song of Sethi’s, written in the particular framework of solidarity with Palestine. The song is a patchwork of two poems by celebrated Pakistani poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz, who wrote against tyranny in a different context. Indeed, politics are deeply woven into much of Sethi’s music. On what embodying solidarity means to him, he spoke about the cultural concept of the mehfil. “Attending a music concert of traditional Urdu poetry has always been a space of solidarity,” Sethi said. “A ‘mehfil’ is an intimate recital of music, there’s a call and answer dynamic going on between the performer and audience. It’s an unplugged intimate setting in which you sing and you chat and you drink…wine, or chai, depending on where in the world you are.” A cheeky smile spread across his face as he spoke on the importance of mehfil in our culture, a form of communal gathering dedicated to poetry and musical recitation.

“It’s a super traditional environment and yet an incredibly freeing environment too. A space for everyone to let their hair down, to sway, to let their inner spirit course through — and it’s about, through metaphors, finding a shared space of emotional vulnerability, of sensual license, of a politic of the soul. And then when I got here to Harvard, and I took history courses and I went to Lamont to look at videos of Nina Simone performing with a piano at the height of the civil rights movement, I would think, ‘Wow, this is related, in some way, to our tradition, in which music is not just entertainment, but it feeds and nourishes our soul…and it’s a kind of congregation. You’re rehearsing a community through beauty, and not conformity.’”

He spoke of the power derived from mehfil in his early years, growing up in Pakistan during a time when it felt like there was a binary of how you chose to live your life. “You could either be westernized and secular and rejecting of your culture; or you could become orthodox and be full of this desire to purge your culture of other influences,” Sethi said. “And this was that other space; music and poetry offered a third space — one of solidarity — which is why I was so drawn to it.”

In the past year, “Pasoori,” the latest addition to Sethi’s musical oeuvre, has shot his name into global stardom: it became the first Pakistani song to top Spotify’s ‘Viral Top 50 Global’ chart and starred in an episode of Disney’s “Miss Marvel.”

Sethi spoke to the alluring form of “Pasoori,” in which he seems to have landed on a formula that invites recitation, even among audiences who may not understand the actual lyrics of the song. “It’s like some of the Punjabi limericks I learned as a kid, which were half-nonsensical, but kind of magical,” Sethi said. “They were built on themselves, and became these fabulous myths with the head of one thing and the tail of another. I think that’s kind of what Pasoori is, a magical being…and there’s something about the structure of it that dazzles and asks for recitation.”

In addition to the infectious beat and stunning vocals, the music video for “Pasoori” — which features a pre-Partition aesthetic, dazzling folk attire, and four forms of traditional dance — has been a huge part of its popularity. And Sethi conceived the visuals for it.

“There are all these epistemologies of love in South Asian culture, which are genderfluid, non-discriminatory, which transcend the usual divisions of caste, language, and class, and go into this place of multiplicity. It’s a chimera: where one is many and many is one. It’s like an acid trip. I really wanted to gesture at this mystical strain of South Asian artwork and philosophy, because that part of our ancestral culture can engage in a fruitful dialogue with contemporary discourse.”

There was another, perhaps more unexpected, source of inspiration for the Pasoori video: TikTok.

“Because it’s a short-form technology, I feel like everyone is using hieroglyphic-like gestures of dance, to start a trend; they’re inviting you to replicate their moves,” Sethi said. “This is what we’ve been doing in South Asian classical dance since forever; in Bharatnatyam, Odissi, Kathak, we do exactly that, communicate by gesture.”

Sethi also just published a piece in the Guardian on the 75th anniversary of Partition, co-authoring it with Indian author Pankaj Mishra. He spoke on its relevance to Pasoori and the state of South Asia today. “It’s about how music offers, especially to the younger South Asian generations, a kind of non-toxic heritage, another avenue to converse and connect and find an alternative pathway to identity that is not necessarily organized religion or nationalism, or anything exclusionary, but rather something that works to root and unite,” Sethi said. “Pasoori was me trying to enact some of that; it was the thesis I never finished as an undergrad, that I never submitted to Professor Asani!”

In conversation, Sethi began musing on what South Asian food dish might best embody his persona. Laughingly, papdi chaat was brought up. He wholeheartedly agreed with the comparison.

“I’m a little bit tart, and I’m a little bit sweet,” he said. “There’s also something very camp and baroque about [papdi chaat] — it’s a little extra, I love it. Campy and baroque…those are the two qualities I aspire to most as a performer. Absolutely write that!”

Through the way he talked about collaborating with other artists and the stories behind his music, it became clear that Sethi is a dreamer. When asked to share his greatest dream, at the moment, he gave a poignant response.

“Aarya, you are the latest manifestation of it,” Sethi said. “When I was an undergrad, Mira Nair came back to accept an award, and I met her for the first time, and now we’re friends who do Zoom riyaz every week…But I remember her saying, ‘When I was a student here in the 70s, there were very few of us here. And now there are more of us here.’ And now, I’m sitting here talking with you, and it’s so amazing to me that here we are, talking about our foods and our music and this is not marginal anymore. This is a part of world culture.”

Sethi’s starry-eyed vision of the future of South Asian art and its place in the global sphere felt like a warm embrace. He shared even greater belief in the diaspora, and its potential to sustain, nourish, and grow cultural art.

“I have started to feel that the South Asian diaspora is a much more fertile, progressive, and inspiring space for me as an artist than mainland South Asia right now, where there are a lot of politics of exclusion going on. And some of that does carry over here to the diaspora, of course, but there is a kind of idealism and this energy in the diaspora that I find completely inspiring,” Sethi said. “I’m connecting with it more and more, working with more diasporic visual artists, filmmakers, fashion-people, makeup artists, writers, musicians, poets. They’re so brave, they’re so generous. They want to connect with each other and they’re so proud of what they come from. My dream is the South Asian diaspora.”

—Staff Writer Aarya A. Kaushik can be reached at aarya.kaushik@thecrimson.com.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.