News

Cambridge Residents Slam Council Proposal to Delay Bike Lane Construction

News

‘Gender-Affirming Slay Fest’: Harvard College QSA Hosts Annual Queer Prom

News

‘Not Being Nerds’: Harvard Students Dance to Tinashe at Yardfest

News

Wrongful Death Trial Against CAMHS Employee Over 2015 Student Suicide To Begin Tuesday

News

Cornel West, Harvard Affiliates Call for University to Divest from ‘Israeli Apartheid’ at Rally

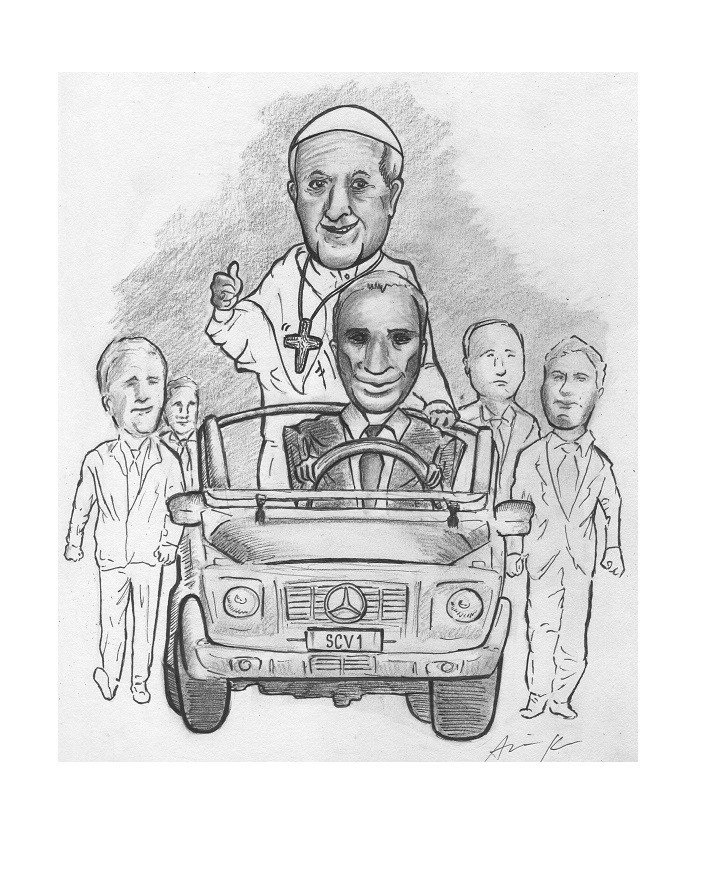

The Confessions of a Guilty Catholic

On the great new pope and Catholic guilt

In 2013, it’s certainly not easy to be a Catholic. Perhaps it has always been this way; after all, the great apostle Peter could not even muster up the courage to say he knew Jesus. And it would be foolish to believe that religion is supposed to be easy; if that were the case, everyone would do it—in the form of Pascal’s Wager at the very least. Yet, it probably isn’t supposed to be this difficult either. While I cannot reject the notion that my upbringing in a Catholic elementary school, wherein we had Friday Mass in addition to regular Sunday services, has skewed my interpretation of fin de siècle secularizing America, I still hypothesize that it has become significantly more difficult to be open about one’s Catholic faith in recent years. In the past two decades, we’ve lost both Pope John Paul II and the Soviet common enemy, a series of scandals has rocked the governance of the Church, and atheism, particularly New Atheism, which believes religion should be militantly countered, has become vogue.

Growing up, I was proud to call myself a Catholic and, even outside of religious circles, that confidence in my faith was looked upon with admiration rather than open scorn. In the past few years, my experience has shifted entirely: While still personally proud to be a member of the one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church, I have done my best not to publicize my beliefs. Although it has been difficult for me to grapple with the exorbitant guilt that has risen out of this fact, I have rationalized my Peter-esque behavior with the belief that my reticence about my faith simply arises from the human condition. Humans can bear disagreements, but there is only so much derision and scorn even the most pious of sinners can take. Tired of being met with contumelies about pedophilia and the Hitler Youth, I am embarrassed to say that I have backed down from the calling of every baptized Catholic to serve as a modern fidei defensor.

Now, as if a reward to those who have remained faithful despite repeated temptations during time spent fasting in the Judaean desert, Catholics have been blessed with a new pope and, along with him, a transformation in the timbre of the conversation surrounding the Church. The liberal elite no longer finds Catholic religiosity completely indefensible—headlines about Pope Francis have taken a 180, praising both the content of his actions and the tone of his message. Even The Crimson supports the new pope, and while many secularists still take issue with aspects of Catholic dogma, suddenly Catholic identification is no longer equated with sympathy for pedophiles and evil (although the decline of the latter position may be due mostly due to the convergence of events that matched the death of Christopher Hitchens with the accession of a reformist pope).

All of a sudden, support for Catholicism no longer elicits eye rolls at best and vitriol at worst. While I wouldn’t go so far as to say that being Catholic is exactly a popular position, especially here at Harvard, the days of attending Mass being an inexpiable crime seem to be waning. Catholics—and I speak mainly for American Catholics—have Pope Francis to thank for this. Of course, stateside support for the pontifex goes beyond rising amour propre. I have to believe that most members of the American communion support the Vatican’s new style and could have only prayed for a pope with such an ability to connect with people. In fact, when I determined to write this column about Pope Francis, I planned to outline the reasons universal approbation is his condign desert.

After rumination and introspection, however, I realized that I could not in good faith write a boilerplate panegyric. Rather, my conscience necessitated that this column be an apology. As has happened many times throughout my life, the famed Catholic guilt has reared its head. It would be disingenuous to pretend all is well, as I come out of the woodwork as a fair-weather Catholic. After all, nothing about the Church proper or about Church doctrine has changed with the transition to Pope Francis. While I am glad that I feel better about my convictions and myself than I did two years ago, higher self-esteem does not atone for my previous taciturnity in matters concerning my religion. I really am proud to be a Catholic, and I always have been, although now I demonstrate my pride with less reserve. I am heartily sorry for my previous offenses to my identity, and I’d like to thank the pope both for his service to the Church and for the role he is playing in my continual effort of self-improvement.

John F. M. Kocsis ’15, a Crimson editorial writer, is a government concentrator in Eliot House. His column appears on alternate Fridays. Follow him on Twitter @jfmkocsis.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.