News

Cambridge Residents Slam Council Proposal to Delay Bike Lane Construction

News

‘Gender-Affirming Slay Fest’: Harvard College QSA Hosts Annual Queer Prom

News

‘Not Being Nerds’: Harvard Students Dance to Tinashe at Yardfest

News

Wrongful Death Trial Against CAMHS Employee Over 2015 Student Suicide To Begin Tuesday

News

Cornel West, Harvard Affiliates Call for University to Divest from ‘Israeli Apartheid’ at Rally

Harvard Archives Gets Digital Upgrade

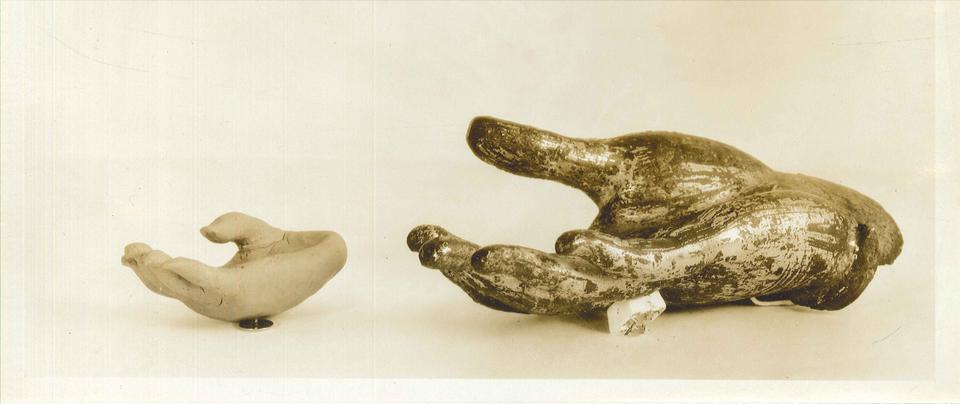

The seventh century “Kneeling Attendant Bodhisattva,” constructed of unbaked clay over a wooden frame, stands a modest four feet high. Pale hands clasped in prayer, legs bent and colorfully garbed, the fragile statue has been on display in the Harvard Art Museums since its arrival in the 1920s. But five years ago, had an art historian wanted to research the story of the statue’s exodus from China to Cambridge or to read curator Langdon Warner’s first-hand description of discovering the piece, the search would have been difficult at the Museums’ Archives.

Last month, the Archives announced the completion of a project to catalog items from its collection, which also include documents concerning the early development of the Harvard Art Museums and letters from T.S. Eliot and Georgia O’Keeffe. Archives materials were also made searchable online and associated with “finding aids” written by archivists. The effort began in 2007, when the Archives received grants for the project from both the Getty Foundation and the Institute of Museum and Library Services’ Museums for America program.

When Archives curator Susan J. von Salis joined the Archives staff in 2003, she says, there was no formal archival program. The Archives, which had been located in the basement of the Fogg Museum, consisted of historically significant documents and letters filed in cabinets that were at one point the victims of water damage. “There were lots of important historical materials, but they were not cataloged,” von Salis says. “There was no way to find them.” When researchers made requests with the Archives, von Salis recalls, a staffer would go by her memory of the Archives’ collection to try to find the material the researchers desired.

Kathryn L. Brush, a professor of art history at the University of Western Ontario, used the pre-cataloging Archive while researching her book “Vastly More Than Brick and Mortar: Reinventing the Fogg Art Museum in the 1920s.” Her search led her to folders and collections filled with history of the Harvard Art Museums: enrollment figures and course offerings; information on past, present, and potential Harvard Art Museum acquisitions; and letters between former Fogg Museum Director Edward W. Forbes and Associate Director Paul J. Sachs. She remembers digging through the Archives’ uncataloged files: “Most of the research for that book relied on what might be called detective work or guesswork because there was no finding aid.”

Brush witnessed much of the cataloging process take place. Approximately 13,800 folders were cataloged, and the Archives finding aids were put online in the Harvard University Library’s Online Archival Search Information System. And as the project continued, archivists unearthed items they did not even know their collection included. “Every day, new materials were discovered,” Brush says.

The Archives holds treasures for art historians or enthusiasts—for example, correspondence by American sculptor Alexander Calder, whose sculpture “The Onion” sits in Harvard Yard, and accounts on the efforts of the “Monuments Men,” who worked to protect and retrieve works of art during and after World War II. For acting Archivist/Records Manager Megan J. Schwenke, letters between American portrait painter John Singer Sargent and former Art Museums directors were of particular interest. “To be someone who has gotten to appreciate a Sargent work in the [Isabella Stewart] Gardner Museum or here and then be able to see words written in his own hand—to me, that’s an art object as well, of a different sort,” Schwenke says.

But, she adds, the Archives also hold materials concerning disciplines outside the arts. “There are so many collections at Harvard for students of art history and just for students who are interested in history in general,” she says. Social historians, for instance, could research former Fogg director Sachs’ World War II-era correspondence, which details how he helped save the lives of curators fleeing Europe. Other materials cover the details of museum logistics, such as documentation of Harvard museums’ finances and accounts of artifact preservation techniques.

Von Salis feels that key functions of the Archives are to provide interaction with primary sources and the context they lend to art and history. “To me, archives are really about the story that the documents tell—you really lose a lot of the picture if you don’t allow yourself to be engaged by the stories,” she says. “You can read about events in a history book, but looking at primary source documentation really makes it come alive.”

—Staff writer Adabelle U. Ekechukwu can be reached at aekechukwu14@college.harvard.edu.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.