News

Cambridge Residents Slam Council Proposal to Delay Bike Lane Construction

News

‘Gender-Affirming Slay Fest’: Harvard College QSA Hosts Annual Queer Prom

News

‘Not Being Nerds’: Harvard Students Dance to Tinashe at Yardfest

News

Wrongful Death Trial Against CAMHS Employee Over 2015 Student Suicide To Begin Tuesday

News

Cornel West, Harvard Affiliates Call for University to Divest from ‘Israeli Apartheid’ at Rally

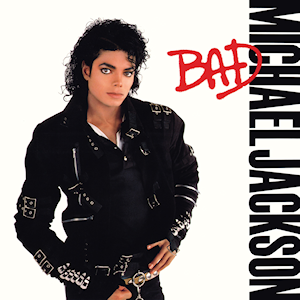

‘Bad’ Turns 30: Revisiting the King’s Rockingest Album

“Bad” has always been my favorite Michael Jackson album. “Thriller” functions too much as a collection of singles, albeit an extremely high-quality one. “Off the Wall” is exceptional, but lacks a certain spark. “Bad” is a far more exciting album than Jackson’s most acclaimed because it’s not only a cohesive album, but it also represents Jackson’s greatest and most experimental foray into rock.

For years, most critics discussed “Bad” predominantly in the context of “Thriller.” Jackson wanted the follow-up to what was already the best-selling album ever to sell twice as many copies. This was in the mid-’80s, when he was by all accounts the biggest star on the planet, but Jackson had yet to make, in his eyes, a complete solo album. “Bad” was supposed to be the biggest album ever, supposedly with planned appearances from Whitney Houston and Prince, so by the time it was released, the expectations were high. It obviously didn’t live up to expectations, and while it was the first album ever to send five hits to the top of the charts, it was seen as overpolished, trying too hard to emulate “Thriller” with less success. Over time, however, it’s become easier to separate the two, and “Bad” on its own is easily the boldest album Michael Jackson ever made.

While “Bad” isn’t sonically cohesive, there’s a subtle unity between the songs as Jackson attempted to prove his maturity through a rock sound. On “Thriller” and on “Off the Wall,” Jackson sounds friendly and almost childlike; “Bad” sees him as more mature and sinister. This isn’t to say that “Bad” is entirely dark—tracks like “The Way You Make Me Feel” and “Just Good Friends” are pretty affable—but more adult themes, like lust and anger, coat the album. For all the contemporary complaints about “Bad”’s overproduction, the album is sonically all over the place, with everything ranging from quieter piano ballads to hard rock.

Jackson and Quincy Jones were masters of album construction, so “Bad” mellows from hard funk on the title track to the softness of “Man in the Mirror” and “I Just Can’t Stop Loving You,” and eventually grows into the hard rock of “Dirty Diana” and “Smooth Criminal.” The varied instrumentation helps express the darker, more mature facets of Michael Jackson: The seductive funk showcases his lust, while the heavier guitars and louder drums expresses a rage and frustration with the world around him.

Michael Jackson’s venture into hard rock is a big part of what makes “Bad” great. The album’s harder sound creates an enthralling sensation that keeps it delightful despite the darker tone and themes. The gated reverb on every song creates a whip-like sensation that gives the album an immensely powerful feeling, punctuating every emotion Michael Jackson feels. On the angriest tracks on “Bad,” these sounds combine to showcase Jackson’s frustrations. “Dirty Diana,” for example, sounds especially dire because of the howling guitars and the way they pair with Jackson’s pained yelps. Jackson and Jones build even the softer tracks with a rock sensibility. “Speed Demon” builds up the same way any typical classic rock song does, if somewhat more understated. But there’s a forcefulness on almost every song that Jackson never possessed before or after, and the rock construction meshes with this to galvanize the album.

Every moment of “Bad” feels huge, and nearly every song gleefully defies what one would expect to come next on a Michael Jackson album. Yet everything comes together seamlessly through the rock instrumentation. The forcefulness on “Bad” meshes with the rock instrumentation in large part because of what it represented in Michael Jackson’s maturation. When “Bad” was released, Jackson was attempting to assert himself as a fully solo artist and wrote nine of the album’s eleven songs. Jackson was able to utilize a harder sound to represent his adulthood and independence. The rock guitars are louder and theoretically less radio-friendly than the pleasant funk pop of Jackson’s youth. Part of why “Bad” is so stellar is the way that Jackson sonically and thematically forces public acknowledgement of his talent through a new genre. By asserting himself as an adult in this fashion, Jackson could gain the respect of people who previously disliked him or didn’t think he made his own music. Even though he wasn’t given the credit he truly deserved for this venture, 30 years later, it’s time he was praised for his riskiest and most experimental work.

—Staff writer Edward M. Litwin can be reached at edward.litwin@thecrimson.com.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.