News

Cambridge Residents Slam Council Proposal to Delay Bike Lane Construction

News

‘Gender-Affirming Slay Fest’: Harvard College QSA Hosts Annual Queer Prom

News

‘Not Being Nerds’: Harvard Students Dance to Tinashe at Yardfest

News

Wrongful Death Trial Against CAMHS Employee Over 2015 Student Suicide To Begin Tuesday

News

Cornel West, Harvard Affiliates Call for University to Divest from ‘Israeli Apartheid’ at Rally

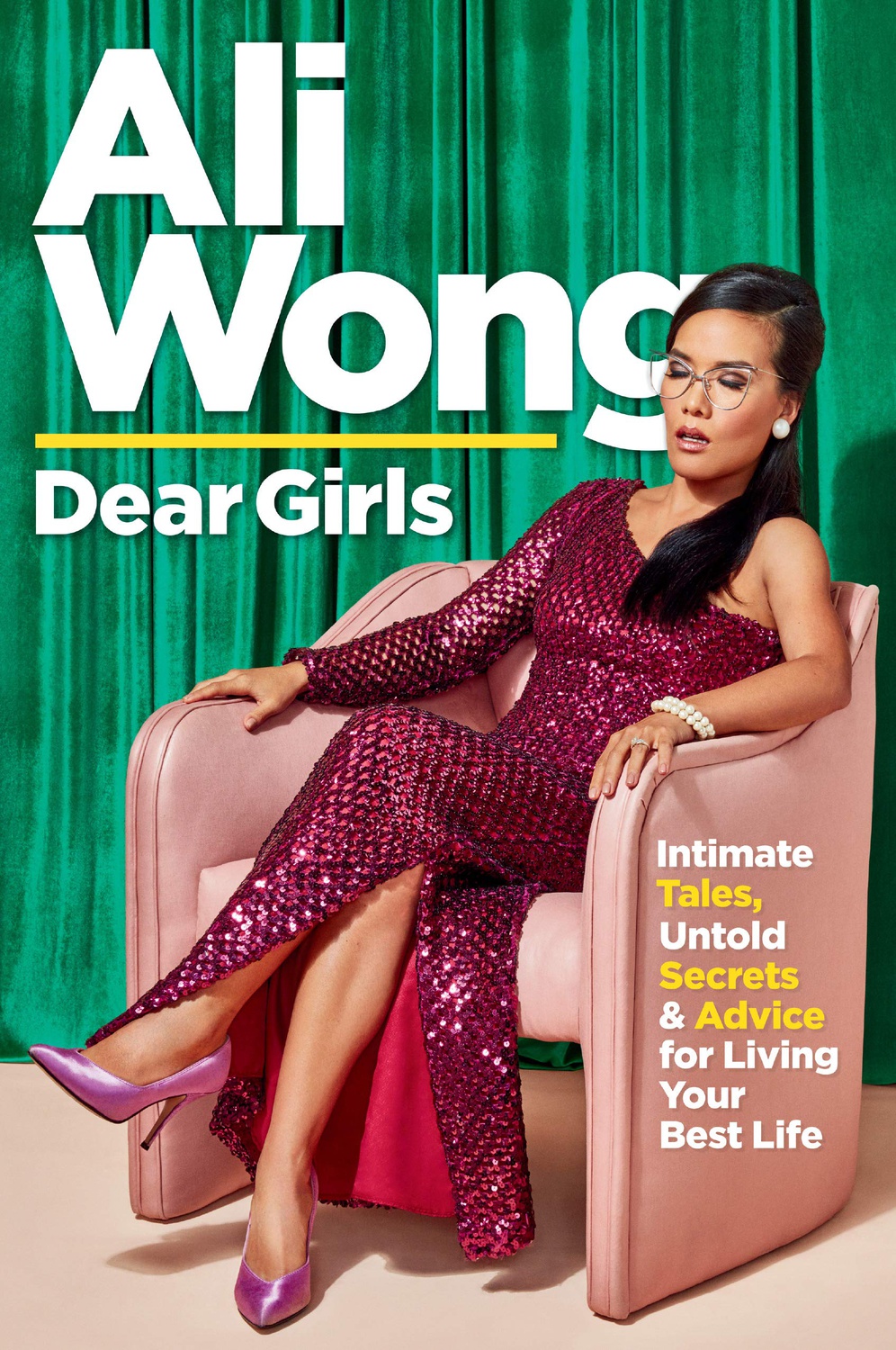

Ali Wong’s ‘Dear Girls’ Is a Wild Romp Through Vietnam and The Comedy World

4.5 Stars

Ali Wong made her name as a standup comic by mooning the crowd as part of her set — she makes sure to tell you that multiple times throughout her essay collection “Dear Girls,” and for anyone who’s seen her Netflix specials, this isn’t that hard to believe. What is hard to believe, however, is that her series of reflections and life tips is somehow even raunchier than either “Hard Knock Wife” and “Baby Cobra,” though this isn’t necessarily a criticism. Actually, it makes each essay even funnier, because anyone familiar with Wong’s particular brand of comedy is bound to read every single word in her voice.

The structure is simple: Each essay starts with the titular words “Dear girls,” as they’re directed to her daughters’ teenage selves, before embarking on the roller coaster that is Wong’s train of thought. She manages to go everywhere before wrapping it up neatly at the end, even though she prefaces the first essay by saying that writing is hard and that she doesn’t like it very much — hence the afterword from Justin Hakuta, her husband, shaman, and ramen expert, that Wong says takes up space in the book so that she can write less. Writing is hard, and she may not like it very much, but Wong is good at it. After all, it’s particularly rare to encounter an author who writes like they speak in real life.

Complaining about why Longchamp Le Pliage bags cost so much could very well be a part of her set: As Wong correctly points out, they are quite literally two pieces of nylon sewn together with a waterproof lining that turns nasty after a decent amount of wear. So could the logical reasons underpinning the clear necessity of taking off one’s shoes before entering one’s house. And, of course, so could her particular aversion to having sex with virgins after having reached a certain age. Basically anything relating to sex, which is a good 50 percent of the book, is easily stand-up material. For practical tips, see page 126 for how to choose a good Asian restaurant and page 171 on how to do a wedding right.

The meat of the collection — and the reason you’ll want to sit down and read instead of sit down and watch Netflix — is insightful and deeply touching, while maintaining the sarcastic voice that makes her instantly recognizable. Wong spends a few pages discussing her miscarriage to normalize what happens to many women, both to and without their knowledge, and to dispel the myth that women are somehow to blame for the miscarriage they obviously did not want. She hates the question, “What is it like to be an Asian woman in comedy?” because she finds it reductive, and would rather spend her time telling budding comedians how she got over her fear of having a joke flop. PSA: There aren’t more women in comedy because of safety issues, even minute ones, that men, no matter how well-meaning, have never had to think about.

“Snake Heart,” her essay on the necessities of studying abroad, is far and away her best, although all of them are pure entertainment that still make readers think. This essay is far more than the typical “study abroad to change yourself” slogan that appears in college brochures and website copy. Rather, Wong writes about the time she ate fertilized duck embryo to show that wimping out over something “gross” that exists outside our culture is not something she’ll tolerate. And she’s right: Sure, you might study abroad to meet cute guys, but if that’s the only reason, you’re doing it wrong. Sit down, and eat the embryo.

That Wong can take other clichés like the term “first world problems” and deal with them in a way that is refreshingly new is telling. For many women, the phrase “running in the dark was scarier than being fat” when describing her dilemma while studying in Vietnam hits home in many different ways, each inducing a slight wince. Wong mentions “trapping” her husband many, many times, but still tugs at heartstrings when she says that the most important part of a relationship is simply being there for the other person.

And, of course, she skewers men who struggle with the earning potential of their wives, noting that “a true feminist husband doesn’t see a woman’s money, power, and/or respect as a reflection of his own lack of success.” Her comedy career wouldn’t exist without her husband helping her both behind the scenes and by her side — a rarity, she implies, in a world when some progressive men still envision parenting as something they can do casually on the weekends, as though becoming a more-than-part-time parent, or even stay-at-home father, would be a last resort. Wong tells it straight: Women are expected to give things up for others — and be okay with it.

Because the collection is directed as a series of lessons to her daughters, there are fewer details of Wong’s backstory about how she made it in the comedy world, and more about her connections to China and Vietnam, and the complicated way that played out in her relationships with her parents. Yet that’s fine: As readers, we’re lucky to have this wildly funny peek into the way Wong really thinks. She may dislike writing, and it may be a long time before she puts pen to paper (or fingers to keyboard) again, but damn — the wait will be a hard one.

—Staff writer Cassandra Luca can be reached at cassandra.luca@thecrimson.com, or on Twitter @cassandraluca_

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.